Notes

Remembering Apollo 11: Techno-Porn and Modernity’s Gamble

by contributor John Lucaites

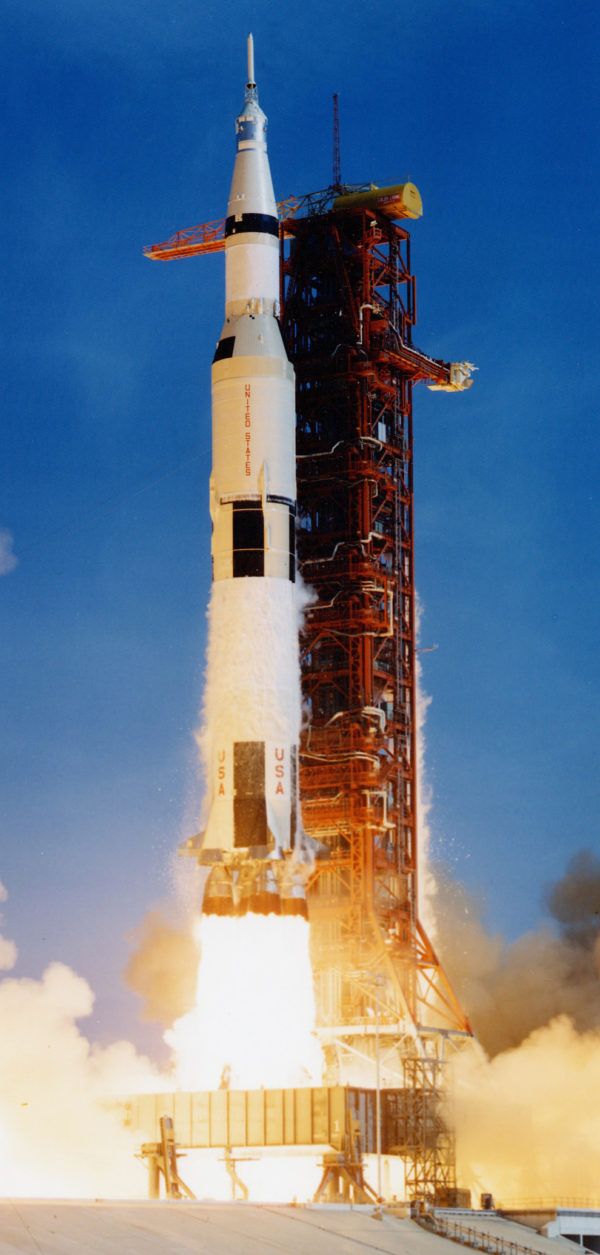

To many, the Apollo 11 moon landing is “the” moment of national triumph in the post-World War II era—marked by recent 40th anniversary slideshows of “remembrance” at major media websites (e.g., here and here). Ritualistic in their representation, these slideshows feature heroes (both the astronauts themselves, as well as the engineers and technocrats that made it all possible) and images of the earth as if shot from the heavens, a vantage that no ordinary mortal could ever achieve. But more than that, these slideshows are dominated by images that fetishize the technology itself, as with the photo above of the Saturn V rocket that hurled the Apollo 11 astronauts into space.

The photograph is a sublime display of raw and unfettered power. I am typically reluctant to concede the all-too-easy identification of a phallic symbol, but it is pretty hard to avoid here.

The long, thin projectile is literally “blasting” off from the launch pad, powered by nearly 7 million lbs. of fuel (according to the caption). And it is not hard to imagine it as a nationalist (notice the red, white and blue color scheme) and technological orgasm, a physical expression of force further accentuated by the sheer size of the photograph itself — a 10 X 20 inch reproduction where I found it, exceeding the dimensions of my 22-inch monitor and requiring I scroll up and down to see the entire thing. In its own way the photograph functions like the Playboy foldout that requires the viewer’s active participation in order to take in the “larger than life” object of desire.

The national media has been complicit with the promotion of NASA and the space program virtually from the beginning, and so I was not really surprised when, in the midst of all the Apollo 11 nostalgia—and visual remembrances we might characterize as vintage techno-porn—I encountered a slideshow at the Sacramento Bee that once again seemed to make a fetish out of our more contemporary space technologies, this time in conjunction with the International Space Station and the recent launch of the Endeavour space shuttle. But what took me by surprise was the slide that ended the show:

The photograph is distinct in a number of important ways. First, of course, is the simple fact that the image features the technology of photography itself rather than the space technology.

There is no way to know if these are professional photojournalists or amateurs, but it is clear that the spectacle is not immediate to ordinary perception but rather refracted through a lens that creates the appearance of closeness or distance, that can expand or diminish the magnitude of the object or event. So, compare the size and distance of the Endeavour image with the photo of the launch of Apollo 11 above. What these photographers can see with their eyes and what they will capture with their cameras is not exactly the same thing. Thus, the photo is a reminder of both the fact and effects of technological mediation. And more, it reminds us the camera is complicit in creating the objects of our desire; no less so in observing the idealized presentation of technological wonders than when we are gazing upon the eroticized body.

But there is a second more subtle, and perhaps more important point as well. Although the billowing plumes of white smoke indicate a powerful force, it is nevertheless a finite power, as we see that what rises must inevitably fall (pun intended).

Indeed, the downward slope of the smoke is reminiscent of those post-explosion Challenger photos, the craft in disastrous descent. Thus, perhaps the image is a cautious reminder of the anxiety accompanying modernity’s gamble—the wager that the long-term dangers of a technologically intensive society will be avoided by continuing progress: every step forward entails some risk, the bigger the step the bigger the risk.

Put differently, for all of the positive effects and affects of our landing on the moon in ’69, our remembrances of the event include virtually no consideration of the cost, including the deaths of the Apollo 1 astronauts, or those who flew aboard the Challenger and Columbia space shuttles. And to remember Apollo 11 in this way is to idealize the event that took place on July 16, 1969, to airbrush it, if you will, in a manner that converts our memory of that day into a fetish.

I wonder if we can separate progress and the risks—the triumphs and disasters—of living in a technological society quite so easily. And if we do, we surely must ponder the ultimate costs.

Cross-posted from No Caption Needed.

(Photo Credits: NASA; John Raux/AP)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus