Notes

Border Trash and the Human Stakes of Migration

I spent this morning reading first-hand accounts of the 1846-48 Mexican War. That war’s primary purpose (and most recognizable outcome) was to establish the U.S. border at the Rio Grande, claiming the Mexican territory lying north and west of it. This afternoon, I’m reading about a national budget that cuts anti-poverty programs and environmental protections in order to find enough money to build a wall along the Rio Grande. In the middle of it all, I am writing about photographs of things taken from migrants apprehended in the desert north of the Rio Grande.

Taken land.

Taken money.

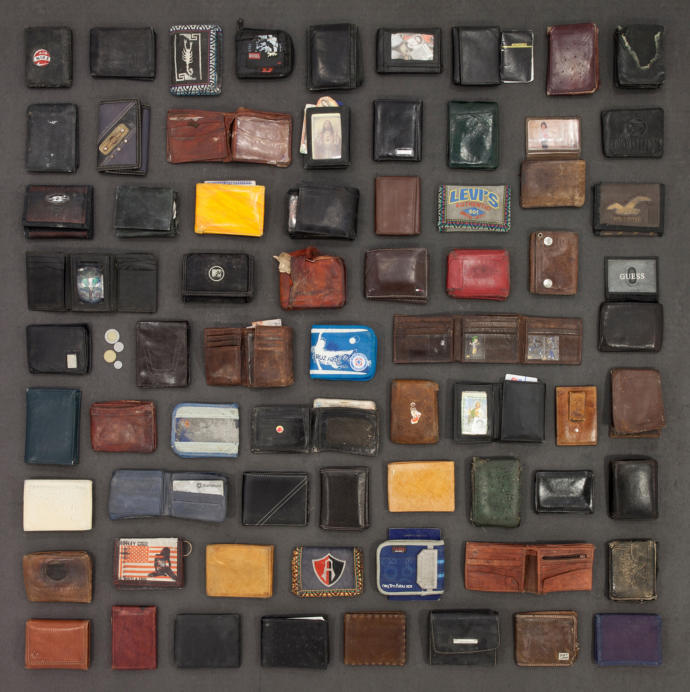

Taken wallets.

Taken lives.

Every day, people walk north across land that—pace Manifest Destiny—should never have belonged to the United States in the first place. Every day, people risk their lives to save their lives, to earn a living, to make a life. If they are caught by U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers, they are brought to processing centers and relieved of their personal effects—anything deemed extraneous or dangerous. Treated as human trash to be dumped south of the border, their abandoned belongings testify to their precarious status.

Tom Kiefer, the photographer for these pictures, is not the first to take pause at the sediments of migration. Environmental agencies, like the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, raise concerns about the effect that clothing, plastic, and other materials have on the fragile desert environment. Anti-immigrant groups circulate pictures of trash-strewn canyons to assert that migration does symbolic and material damage. Hana Masri, who studies the rhetorics of migration, puts it succinctly: in these arguments, “Border ‘trash’ thus serves to both render migrant lives disposable and evidence that disposability by representing migrant death.”

On the other side, activist groups such as Humane Borders leave caches of water in the Sonoran Desert to provide life-saving liquid for migrants and activist programmers designed an app to help migrants find those caches (the U.S. Border Patrol has been known to destroy them). The group Los Desconocidos has started the Migrant Quilt Project that makes quilts to memorialize migrant deaths using clothing left behind in the desert. Artists Valarie James and Antonia Gallegos, likewise, have used things left behind by migrants to make monuments to the people who made the crossing.

Making art from these objects left behind has an inevitable political and ethical valance. As Sonia Arellano, who studies and participates in the Migrant Quilt Project, explains, “My sewing machine has a thin layer of desert dirt on it from piecing the jeans together. I am acutely aware of my privilege in completing this quilt as it is starkly juxtaposed with the migrant stories conveyed through the clothing.” Kiefer, too, acknowledges this when he notes that the apparent brightness of his work has occasioned negative comparisons with the work of photographers like John Moore whose pictures draw more explicit attention to the politics of migration and feature the faces and stories of migrants themselves. These artists, activists, and commentators all share, however, a sense that making trash visible in new forms and contexts will alter perspectives, making public the human stakes of migration.

Without dismissing that hope, I’d like to focus our attention on what comes clear in Kiefer’s photographs precisely because of what makes his work different from the trash-focused projects invoked above: Kiefer’s photographs memorialize the detritus of migration after detention. In them, we see not only objects belonging to migrants but also the hand of U.S. immigration bureaucracy that took those objects. Migrants and bureaucracy co-exist in these photographs and that gives their careful ordering a particular resonance. They become a carnival mirror for border enforcement: migrants are captured and processed, their belongings discarded //after the migrants themselves have been passed along—discarded—those belongings are recaptured and processed into photographs. On both sides of the carnival mirror, extreme order attempts to process the human disorder produced by inhumane borders.

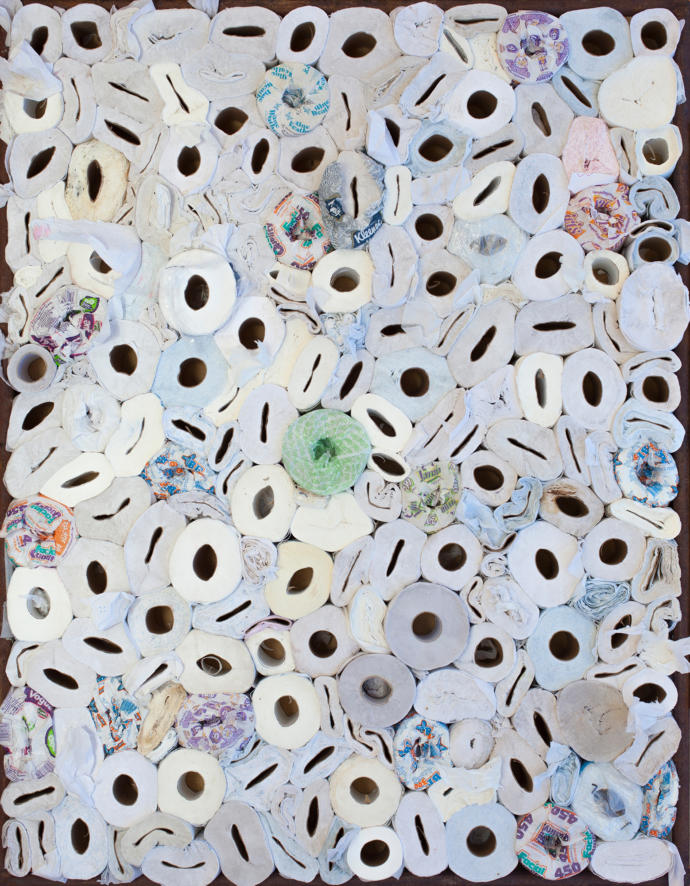

Kiefer’s photographs featuring personal hygiene products are perhaps most eloquent on this front. Rolls of toilet paper huddle together for safety, toothpaste and toothbrushes swim enmasse toward an unseen border, sticks of deodorant cluster against a wall made of cigarettes and lighters.

Each individual roll (or tube or brush or stick) summons up the routines of bodily integrity migrants follow as they travel. Placed side by side, tightly packed in neat rectangles but separated from the people who carried them, those same items remind us of the scale of human movement involved here. They also direct our attention to the dehumanization explicit in border enforcement and to the absolute humanness of migrants. Everybody poops. Everybody sweats. Everybody wakes with bad breath.

The regimented rectangles of Kiefer’s photographs force us to see, though, that “processing” makes the products that migrants carry with them into trash. It strips them of the accoutrements of civilization while portraying them as a threat to civilization. Re-ordering trash, Kiefer’s pictures stand witness to the trashing of people that happens every day on the U.S. border.

— Christa Olson | @christajolson

Photos: Thomas Kiefer/INSTITUTE Caption 1: After being apprehended, a detainee’s belonging are either placed in a property bag or remain in the backpack that he or she travelled with. Sometimes, essential items such as wallets and personal identification are discarded. Caption 2: When migrants are apprehended, Customs and Border Protection agents dispose of personal-hygiene items such as toilet paper during intake.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus