Notes

News Photos as Military Promo: Prepping for the Next Good War?

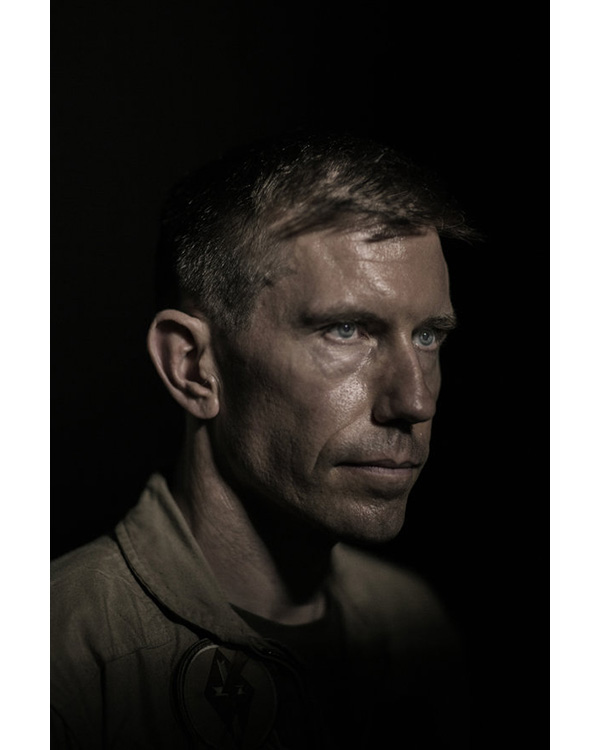

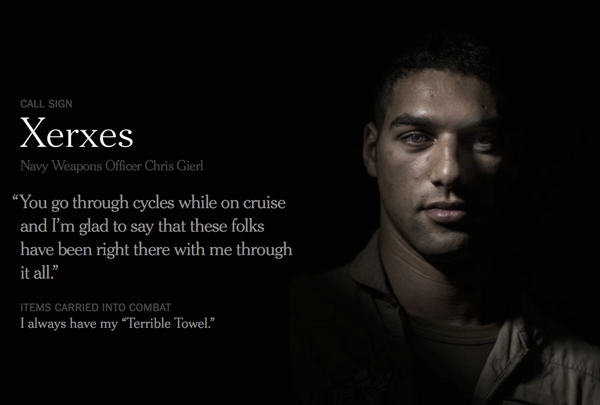

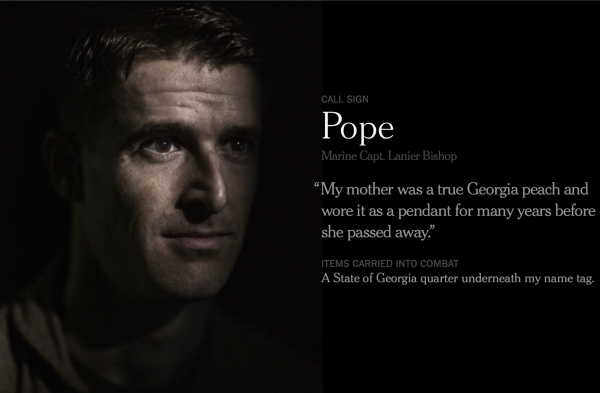

If you’re passionate about photojournalism, I imagine you’ve already seen the bold interactive NYT feature, “The Pilots Fighting ISIS,” published last Wednesday. And if you did, were you also unnerved by the layout and the portraits of the Navy fighter pilots? Was it a bit too “Hollywood”? Did it seem to hark back to WWII and the idea of “a just war”?

There is something very unsettling for me in these images – a message laying just below the surface of a societal mindset I am not really comfortable with. Not since seeing James Nachtwey’s image of a wounded “Contra” being moved Christ-like through the Nicaraguan jungle have I felt a presentation as a harbinger of coming political change.

As some suggest, it’s certainly PR for the military. And it brings up the requisite questions of who picked these pilots? Why them? Who set up the access and where did the idea — in its outsized scale, drama and intimacy — come from? (According to the article, the photographer, Adam Ferguson, is on assignment for The New York Times aboard the U.S.S. Theodore Roosevelt, in the Persian Gulf.)

I think there is more to it than that, though. For some time, I have been trying to grasp how to talk about the other side of the camera: namely how, why and when photos are used and what it says about social, cultural and political pressures on editors. I don’t necessarily mean overt boardroom or editorial meeting decisions as much as what happens when you hang and talk with people in your business.

I think this piece is all about that. It is not that this kind of work hasn’t been done before, or wouldn’t have found such a prominent place during the bombing of Libya, for instance. But now, the enemy is much more “evil” and, in fact, seems to go out of it’s way to re-enforce that idea in “our” side.

Anyway, these images, to me, seem to be about way more than just PR.

During the early years of the Vietnam War (note: I was not in Vietnam either as a soldier or a journalist), coverage was done “on the ground” as well as the “Five o’clock Follies,” the weekly press briefing in Saigon. What journalists soon realized was that the Follies bore little resemblance to what was going on in the field. They began to ignore, or at least minimize the Follies statements, in favor of what they were seeing and hearing on the ground. When they sent these stories back to the desk, especially in the trend setting papers (LA Times, WSJ, NYT, WaPo) the editors didn’t accept what they were hearing. The reason was the editors, political reporters and national reporters had their sources in the Departments of Defense and State, as well as the White House, and those sources said the reporters were wrong.

The coverage only changed when and because the perception of the war and the political/social climate finally changed.

The point here is we all have “trusted” sources and social circles that determine how we see stories and what we accept. If you and I were in a position to affect what runs and how it’s displayed, it would go the same way. The social circles are made up of our work peers and determined by economic strata, backgrounds, etc.

It is hard to imagine how coverage of the poor/homeless/working class is accomplished in any meaningful way, I might add, by someone making way north of six figures, living in a comfortable high-rise with neighbors and social companions who are the elites of whatever endeavor they are in. (In a non-photo context, think about the current political coverage of the recent Labour leadership vote in England. It was and still is accepted dogma that Corbyn was non-electable – first as leader and now as PM. Even the Guardian had taken this position. In this country, Bernie Sanders continues to make inroads on Clinton and yet it is Biden, who is not running (yet), that is seen as her most likely threat. If Sanders wins in Iowa and NH, that will change.)

So, as to the series at hand: “rah rah” pieces certainly didn’t start with this spread of portraits and there are countless examples far more “Hollywood” than Ferguson’s actually pretty straight-foreword photo essay. At the same time, though, as has been pointed out at this site many times, photographic meaning is often derived in its use. What I think is happening here is this: Iraq, Syria, Libya, they are all represented to US citizens as not particularly “nice” regimes. This framing might be useful, depending on the timing, but as potential threats or outright menaces, these countries are relatively harmless to us.

So the coverage of these players is a bit ambiguous and ebbs and flows with the wind. With ISIS, I am reminded of pols in 1964 saying if we didn’t send in the troops to Vietnam, we would see the Communists on the steps of Seattle. Just who (short of Rand Paul and I, believe, Sanders and Corbyn) is going to say maybe there is a better way. ISIS is playing it’s part: killing and destroying, as well as recruiting and threatening … with maximum buzz. And while I don’t think we’re at the threshold yet, ISIS has been so undermining and disruptive, I believe the country is close to accepting the idea of a “good war.” And, that’s what I think this NYT spread is all about.

As for the photos themselves, the men in these images are out of “central casting” (I won’t go into the fact they are all white males, which would lead us into a discussion of race, opportunity, class, etc.). They are “steely eyed” heroes in the mold of WWII Hollywood.

They are all “our boys” from next door. They always say sir and madam. They believe in God and the rightness of “our” way of life. If they go down, they will do so with their ring finger rubbing the image of their wife. They say all the right things: nothing more, nothing less.

These photos and text all bring up images of a better time, a time when America knew who she was, how to act, how to LEAD. When everyone knew this was God’s land. To emphasize again: I don’t see this feature as part of a conspiracy to take the country to war, or to give more power to the military industrial complex. It is, though, about the tipping point. If a military stand against ISIS is coming, not one that chips away at the edges but delivers us, across the front pages, to a unified commitment, outsized features like this will have helped pave the way.

— Robert Gumpert

(photos: Adam Ferguson for the New York Times)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus