Notes

When Different Wire Photos on Same Story Address Different Racial Audiences: “Go Set a Watchman”

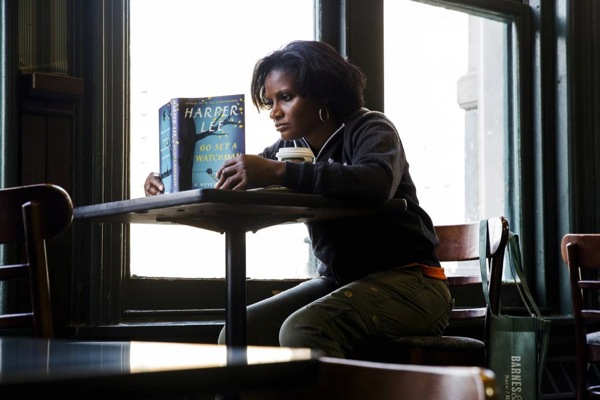

These two Reuters photos, one picturing a black woman reading Harper Lee’s “Go Set a Watchman,” and a white man with his granddaughter anticipating its arrival, visualize an America that remains divided along racial lines.

Alongside each other, they are a study in contrast: different contexts, different races, different genders. The more immediate question they raise, though, is: Who is invited to see themselves as Watchman’s audience? If these pictures were meant to assuage anxieties regarding contemporary race relations – “Look, these Americans are sharing a common experience!” – they actually do the opposite. In fact, they picture two different Americas.

The black woman’s “America” is contemporary and metropolitan, as suggested by her clothing: sweatshirt, cargo pants, and hoop earrings, as well as the Barnes & Noble tote bag; the coffee to-go; and the franchise’s wooden chairs that only look relaxing. (And, on a separate note, it may even bring to mind Starbucks’s ill conceived “Race Together” campaign.)

The woman’s face (Given Atticus’s character development) seems to reflect a story she knows all too well – the story of this nation’s histories of micro- and macro-aggressions against non-white citizens. Lost in Lee’s prose, her expression seems steadfast, but unapproachable. Except for the sunlight on the woman’s face, the interior is mostly dark and shadowy. That uninviting quality, paired with her expression, makes me feel voyeuristic – like I am sneakily going where I am not supposed to go.

As much as the photo of the black woman pushes me away, however, the photo of the white family draws me in. Here we see Tony Lyerly and his granddaughter, Mariah, waiting outside of the Ol’ Curiosities & Book Shoppe in Lee’s hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. This photo, too, amplifies elements of context and time, but in competing ways. The Lyerly’s “America” is not urban, but rural. Although the background is sheer darkness, because it’s absent any town or cityscape, we’re divorced from civilization, as if the photographer wandered upon them after traveling down a back road. (And let’s not forget that the bookstore they’re waiting at is named “Ol’ Curiosities,” a textual reinforcement of the setting through its phrasing.)

The photo of the Lyerlys also presents as rural because of the overalls, t-shirt, and short-sleeve collared shirt – a “farmer-ly” aesthetic that comes across as plain, simple, yet sturdy. While the first picture reads as a “photo of the now,” this second one almost seems like Tony and Mariah stepped out of a page of the book they are waiting to purchase.

Of course, the “history” of the photo is challenged by the glow of the screen that lights up Mariah’s face. (And just look at that face, aglow with an innocent curiosity that is almost infectious.). But while the lighting in the first photo is uninviting, the light from Tony’s screen pulls not only Mariah into the medium– it also pulls viewers into the photo, as well. Warm and welcoming (while someone else might say, reeking of Southern hospitality), I don’t feel at all like a voyeur, at all. It makes me want to sit alongside the Lyerlys.

But as different as the people and the settings are, perhaps the most critical difference between the pictures is the access to the text. The photos suggest that the people in both images are reading “Watchman,” but the captions suggest otherwise: the African American woman is reading Lee’s novel, but the white family isn’t. They can only anticipate its arrival (even if the photo itself suggests that they are consuming Lee’s work).

So, while the African American woman is encountering aggressions and unjust race relations, the white family wants to access this text and its perspectives and ideas, but they can’t.

This photo, for me, asks us to read them as perhaps not ready to access the text that they desire. I think that there is something to be said about how that dialogues with the (white) public’s response to Atticus’s character development in Watchman. They don’t want to, or are not ready to lose Atticus as their moral protagonist — to see him as a flawed human. It shatters a myth and reveals an illusion, forcing white audiences to reckon with a past (and present) that they perhaps do not want to see.

So I raise the question again: Who, between these photos, is invited to see themselves as Watchman’s audience?

— Katie Irwin

(photo 1: Lucas Jackson/Reuters caption: A customer reads a copy of Harper Lee’s book “Go Set a Watchman” after purchasing it at a Barnes & Noble store in New York, July 14, 2015. “Go Set a Watchman,” the much-anticipated second novel by “To Kill a Mockingbird” author Harper Lee, is the most pre-ordered print title on Amazon.com since the last book in the “Harry Potter” series, Amazon said. photo 2: Michael Spooneybarger/Reuters: caption 2: Tony Lyerly and his granddaughter Maraih Lyerly, 3, wait with others to buy “Go Set A Watchman” at Ol’ Curiosities & Book Shoppe in Monroeville, Alabama July 13, 2015. In the southern hometown of author Harper Lee, a freight truck unloaded the first of 7,000 copies of “Go Set a Watchman” at a small bookshop just ahead of midnight, minutes before Tuesday’s release of Lee’s first published novel in 55 years.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus