Notes

From His Own Perspective: The Seductive Power of the Instagram Migrant

From: How Photographers Are Trying to Put a Face on Europe’s Migrant Crisis (TIME). caption: A family of Syrian refugees holds its identification. Nearly 300 Syrians landed in the port of Catania, Dec. 6, 2014. (photo: Alessio Mamo—Redux)

As many of you know by now, the story of the Instagram Migrant is about a supposed migrant, posing for a real production company, using Instagram to supposedly chronicle, in the words of this misbegotten HuffPost’s piece:

…the joy and fear of his journey from North Africa to Europe in a serious of posts showing him terrified on a small boat, hiding in a truck and being manhandled by police.

Oh joy, right?

The Instagram Migrant story was broken by Amin Musa and Lewis Bush in his original post. Eliza Mackintosh at Storyful does a deeper breakdown of the subterfuge and David Campbell’s post at Storify is noteworthy not just for his timeline of the story of the story, but for his deeper questions and thoughtful conclusions. While Lewis and David apply serious thought to what this clickbait says about the state of journalism and the need for best practices, however, what I’m most interested in are the media- and the cross-cultural conditions which provided this actor with such a prime opportunity in the first place.

Responding to a similar situation last year, as well as to Lewis’ disclosure he once considered creating such a fictionalized narrative, David makes the point that we don’t need fakery when so much quality work has been done visually documenting the odyssey of migrants. It’s in elaborating that point that he makes an interesting distinction, one we might benefit from holding up to a magnifying glass. He writes:

The global movement of refugees is such a significant issue, and the politics around it are so morally problematic, using it as a prop, or doing anything which can lead audiences to cast doubt on the worthiness of asylum seekers, is fundamentally irresponsible. And that is all the more so when you think good documentary work has been produced for a long time. If you want the migrants perspective, you could do a lot worse than start with the 2006 Olivier Jobard/MediaStorm film “Kingsley’s Crossing” …. the story of one man’s dream to leave the poverty of life in Africa for the promised land of Europe … or The Guardian’s “The Journey”, recounting the story of a refugee fleeing Syria for Sweden….

The critical phrase here for me is: “the migrant’s perspective.” Perhaps the true blindspot in the journalistic field of vision, even when “the perspective is the migrant’s,” is that we’re always seeing through the reporter’s (largely western) filter. Lewis strikes closest to this factor when (bold type mine) he writes:

The journey depicted here fits has all the hallmarks of the type of stories reported daily in the press, of arduous journeys across deserts, of corrupt people smugglers, of treacherous sea crossings only to be confronted by indifferent police officers and internment. I had for a while been wondering if we would ever see photographs from a migrants perspective, and when I first encountered ‘Abdou Diouf’ I was fascinated.

Of course, we would hope that the migrant diaspora in our media diet would reflect the greatest realism, but that’s a whole different thing than the migrant telling his or her own story, taking his or her own pictures, and controlling his or her own narrative.

Perhaps the reason why Abdou Diouf’s Instagram account was so seducing, despite all the contravening clues, was because of the rare offer of migrant photos that were unmediated.

To be perfectly honest, I think we’re better off for this controversy, if just to punctuate this point. For the past year or so, a popular story concept in photojournalism — to the extent it might even qualify as a genre — has been that of “migrant portraiture.” Some of it has been unusually empathetic. Some of it has engaged provocation. Some has gone an overtly artful route. Some, to be honest, has been cringeworthy. Here is a sampling with links, and you can consider the spectrum for yourself:

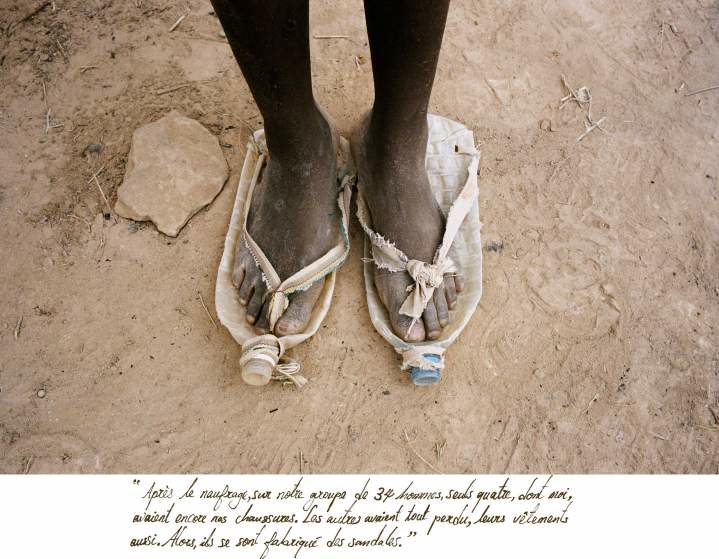

From: How Photographers Are Trying to Put a Face on Europe’s Migrant Crisis (TIME). caption: After a shipwreck off the coast of Morocco in Nov. 2004, only four of 34 men still had their shoes. The others lost everything, including their clothes, and had to make sandals out of makeshift items such as plastic bottles. (photo: Olivier Jobard – MYOP.)

From: Mediterranean migrants: Portraits of people who have crossed from Libya to Italy by boat [Photo report] – IBT. caption: Nineteen-year-old Tasha from Nigeria poses for a portrait in Lampedusa. After making the journey from her home country, Tasha spent one day on a boat from Libya before being picked up by the Italian coast guard (photo: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

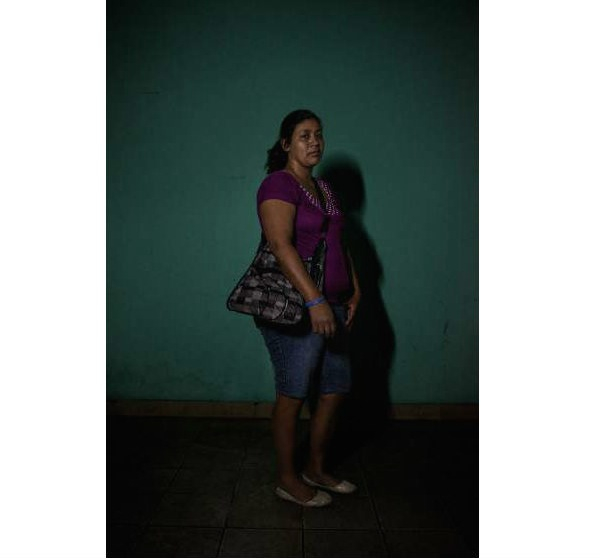

From: See What Undocumented Immigrants Carry Across the Border (TIME Lightbox). caption: Delmis Helgar, 32, from Honduras. She is in a hurry to reach Houston where her little daughter is living with relatives, after her ex-husband was recently deported. In her bag was a make-up set, hand mirror, lip gloss, deodorant, a shirt, a small bible, face gel, a wallet, a cell phone, pills, a battery charger, hair band and two pantyliners. (photo: Emanuele Satolli.)

From: From one nightmare to another. AFP Correspondent Blog. (photo: Christophe Archambault/AFP)

From: The story behind the photos of Syrian refugees escaping along the ‘Black Route’: Part 2 (Washington Post). caption: An Afghan man and a little girl, among others, had been staged at this camp just inside Macedonia for a couple of days. (photo: Charles Ommanney/The Washington Post)

From: The experience of African migrant workers in Italy. (Washintgon Post). caption: Puglia. Tomato harvest. (photo: Alessandro Penso/OnOff Picture)

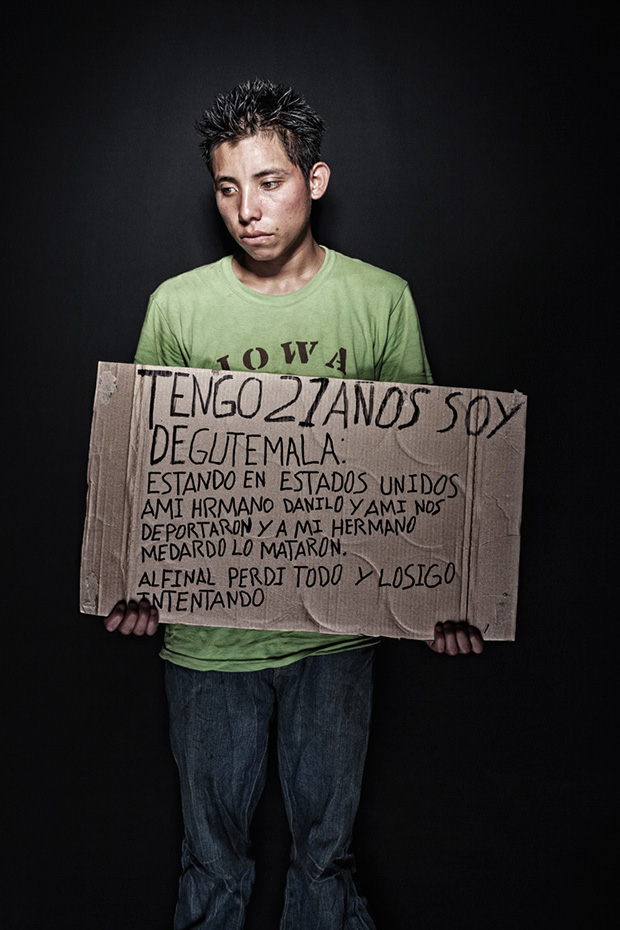

From: ‘The Other Side of the American Dream’: Powerful Portraits Document the Abuse of Migrants Passing Through Mexico. (Featureshoot.) caption: “I’m 21, from Guatemala; while in the U.S. my brother, Danilo, and I were deported, and my brother Medardo was killed. In the end, I lost everything and I keep trying. ” – Ixtepec, Oaxaca, 2011. (photo: Nicola “Ókin” Frioli.)

The point to emphasize though, looking at this work (representative of dozens of stories drawn from our Evernote file), is that it has one thing in common: None of it is of the migrant, by the migrant. Like Lewis said, how fascinating that would be.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus