Notes

Volcanic Exceptionalism: Why America Treats Every Disturbance Abroad Like it’s Looking in a Mirror

Volcanoes make fabulous metaphors. They call up angry gods, warn of impending war, deal out catastrophic punishment for cultural decadence, and foreshadow ecological collapse. It’s no surprise, in other words, that photographs of the unexpected double eruption of Chile’s Calbuco volcano captured public attention last week. Not only are those photographs terrifyingly beautiful, they also resonate with our available metaphors. BagNews’ recent take on how those photographs echo the apocalyptic mood of recent television and film captures that point perfectly.

It may be the case that we’d see similar photographs no matter where in the world the volcano was erupting. But, as someone who studies the history of pictures circulating between the United States and Latin America, I can’t help but see these photographs of Calbuco’s eruption as part of a longer story. People from the United States have been looking at South American volcanoes and seeing them as metaphors for what’s happening here (in the US) for at least one hundred and fifty years.

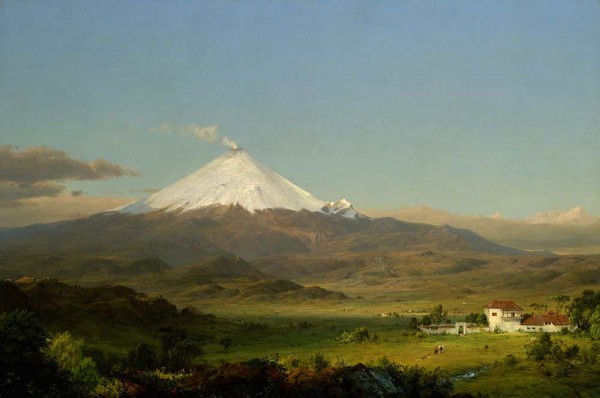

Frederic Edwin Church, “The Heart of the Andes, 1859. Oil on canvas, 66×119 inches. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Frederic Edwin Church, the most famous painter of the mid-nineteenth-century United States, traveled to Colombia and Ecuador in 1853 and returned to Ecuador in 1857. His best-known painting from that trip, “The Heart of the Andes,” appeared in 1859 to wide acclaim. People in New York City stood in line for hours and paid twenty-five cents each just to get into a crowded room to look at it. In addition to that massive masterpiece depicting an invented Andean landscape, though, Church also painted at least ten different versions of Ecuador’s perfectly conical volcano, Cotopaxi. Those paintings are now visible in museums across the United States—at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and more. Ironically, despite the fact that he painted the volcano several times before 1857, Church only saw a partial view of Cotopaxi without cloud cover during his 1853 trip, and he missed out on a full-scale eruption by a matter of days. That didn’t stop him from depicting the volcano in many different moods and for shifting purposes over the course of fourteen years, though.

Frederic Edwin Church, “Cotopaxi,” 1855. Oil on canvas, 28×42 inches. Collection of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art

Frederic Edwin Church, “View of Cotopaxi,” 1857. Oil on canvas, 24.5×36.5 inches. Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Frederic Edwin Church, “Cotopaxi,” 1862. Oil on Canvas, 48×85 inches. Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts

It is nearly 3,000 miles from the battlefields of the US Civil War to the cordillera of Ecuador’s central highlands, yet as the War progressed, Church’s Cotopaxi went from a tranquil mountain to an ominous volcano. Romantic calm gave way to impending doom as the United States tore itself apart. When Church’s northern audiences looked at that far away volcano towering over a blood-red pool, they were primed to see the violence of sectional strife and the bitter wages of slavery staring them down from half a hemisphere away. They saw their own national anxieties reflected in Cotopaxi as surely as they would appear in Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address three years later.

This tendency to see US storylines in Andean scenes wasn’t a mistake. By the mid-nineteenth century, audiences in the US regularly saw manifest destiny stretching their nation across the American continents. Looking hard at Andean scenes, they became increasingly American viewers, well equipped with the visual vocabulary of exceptionalism. In his pamphlet describing “The Heart of the Andes,” Church’s friend Theodore Winthrop gives us a succinct, yet grandiose, statement of how essential that American audience was. For him, the Andes only really existed when seen by great observers:

“Long ago, in the dim cycles, Incas watched the snowy Andes for the daily coming of their God, the Sun. Then the barbaric music of those morning oblations died away, and, except for Potosí [Spain’s famous silver mines in colonial Bolivia], the Andes might have been quite forgotten. First again we hear of them as a scientific convenience. … The world began to respect these mountains as pedestals for science; but later, as the Himalayas went up, the Andes went down. … By and by came Humboldt and lifted the Andes again… He told, also, of their grandeur, and invited mankind to recognize it. But their transcendent glory, as the triumph of Nature working splendid harmony out of brilliant contrast, remained only a doubt and a dream, until Mr. Church became its interpreter to the northern world.”

Whatever Winthrop says, I’m quite sure that the millions of people who lived in the shadows of the Andes from pre-Colombian times through the mid-nineteenth century neither forgot nor doubted their existence. Cotopaxi had twelve confirmed eruptions during the 1850s and there were some twenty-six recorded eruptions throughout the Andes that decade. Those things are hard to miss when they’re right on top of you. Yet for Winthrop, they only really came into being when the northern world looked at them.

It’s harder for viewers in the US today to have quite so solipsistic a picture of the Andes. Many of the timelapse videos of Calbuco we’ve been seeing were captured by residents of the towns threatened by the eruption, and those people pass in and out of the scene as we watch it develop. Even so, past scenes and ways of looking inevitably haunt today’s photographs, and the particulars of Calbuco quickly become fodder for American stories.

Maybe it’s relative proximity, maybe it’s a shared American-ness, maybe it’s that Latin America has long been a laboratory for US influence in the world. Whatever the cause, it’s almost inevitable that a message for the United States gets wrapped up in powerful pictures of Andean volcanos. Based on recent commentary about Calbuco, I’d hazard a guess that this time around the message is about ecological irresponsibility and the moral imperative to address climate change. Calbuco’s cloud of ash and fire, wrapped in electrical storms and towering threateningly over streets and homes is just distant enough to inspire reflection and just close enough to drive itself home.

–Christa Olson

(photo 1: Carlos F. Gutierrez / AP. caption: Children watch the Calbuco volcano erupt, from Puerto Varas, Chile, Wednesday, April 22, 2015. The volcano erupted billowing a huge ash cloud over a sparsely populated, mountainous area in southern Chile. Authorities ordered the evacuation of the inhabitants of the nearby town of Ensenada, along with residents of two smaller communities. photo 6: Francisco Negroni//AFP/Getty Images. caption: This view from Frutillar, southern Chile, shows a high column of ash and lava spewing from the Calbuco volcano, on April 23, 2015. Chile’s Calbuco volcano erupted on Wednesday, spewing a giant funnel of ash high into the sky near the southern port city of Puerto Montt and triggering a red alert. Authorities ordered an evacuation for a 10-kilometer (six-mile) radius around the volcano, which is the second in southern Chile to have a substantial eruption since March 3, when the Villarrica volcano emitted a brief but fiery burst of ash and lava.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus