Notes

Belgian Distress Over World Press Winning Pictures: Considering News Photos in a Larger Atmosphere

If you don’t follow the photo world all that closely, an intense debate has broken about the first place prize for Contemporary Issues by Giovanni Troilo in the latest World Press Photo awards. The series, titled “The Dark Heart of Europe,” encompassing 10 photos illustrating “the collapse of industrial manufacturing, rising unemployment, increasing immigration and outbreak of micro-criminality” in the town of Charleroi, near Brussels.

As far as World Press and most of the photo world is concerned, this debate has to do with charges of staging and accurate captioning based on criticism leveled at the work by Charleroi’s mayor, Paul Magnette. In its technical response, World Press defended the work, pointing out in thorough detail how the creation and description of the work was as all above board. (In one photo, the photographer captured his cousin having sex in the back of a car. In another, he documented the scene of a husband and wife engaging in an S&M ritual.) If the photos can be justified on photo contest grounds, mindful of the fact that the Contemporary Issues category of World Press is not the same as hard news, what largely escapes the photo contest is the truer source of the Belgian ire. If the Mayor got caught up in issues of lighting and staging, his deeper complaint has to do with Mr. Troilo characterizing his city as “the black heart of Europe,” or a rotting entity riddled with depravity.

Unfortunately, the question of how to visually depict urban challenges or depressed cities has been treated as more of an aesthetic exercise, an academic issue or just earnest effort by the photojournalism world. The fact that mayors, city representatives, local photographer/journalists or the public-at-large would take issue with such depictions has been treated by news publishers and certainly the photo establishment as misplaced, as if it were a misunderstanding of press photography rather than some misunderstanding on the part of the industry or insensitivity toward the public.

Interestingly, the controversy over the photos from Belgium (and the inconvenience for the industry) is not a new example, just the latest one. At Photoville 2013, for example, I related the circumstance of citizens from Utica becoming upset over Getty photographer Spencer Platt’s depiction of inner-city blight in a photo story from May of 2012.

Not hours after Getty photographer Platt’s photo-story about the urban plight of downtown Utica was published, angry residents and officials in the city took to Twitter and Facebook to voice their discontent. Picked up by the Albany Times Union, USA Today and other publications, Utica Mayor Rob Palmieri and the Downtown Utica Development Authority showcased the photo story on Facebook.

Here, a local photographer and blogger, Eric Meier, posted his rebuttal to Spencer’s work, actually juxtaposing Spencer’s photos with shots of his own with a different view and feeling of the same locale. Platt and I discuss the backstory in this video clip from the BagNews “Photojournalism in Flux” panel September 2013:

Although the controversy in 2013 surrounding Paolo Pellegrin’s misrepresentation of a World Press winning and also Picture of the Year winning photo alleged to have been taken in the depressed, inner city Crescent area of Rochester attracted overwhelming attention of the photo community (full disclosure: BagNews was the source of that disclosure), there was also a social reaction to the story.

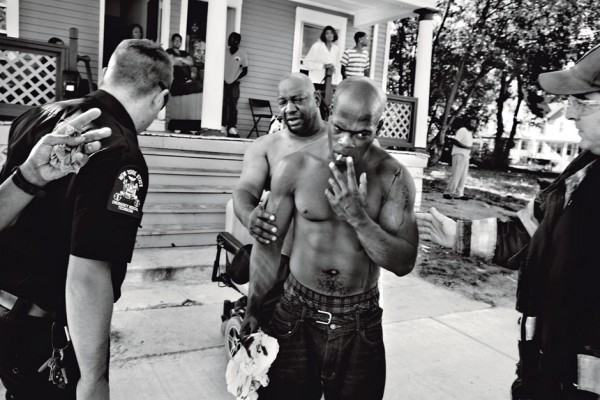

Underlying the attribution issue was the fact that most of Pellegrin’s photos of the Crescent that ran in Die Zeit in January 2013 before being submitted to WPP and POYi — many the product of police ride-alongs — characterized this one district in a thoroughly wanton way.

Overlooked in the industry firestorm over captions and context was the consternation over racial, social and primarily civic stereotyping including reaction from local press, and in a notable instance, the concern of a local professor with a respected blog on photography and politics. Max Schulte, a longtime photographer and editor at the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle and a former RIT student (which hosted the photo project) took Pellegrin to task for his insensitivity. In On Politics, Theory and Photography, University of Rochester professor Jim Johnson wrote:

“I have to say that while the photography, unsurprisingly, is striking in many ways, the overall story Pellegrin presents is rather shallow and moralistic. We get a cat and mouse interaction between drug dealing ghetto youth (mostly racial/ethnic minorities) and officers (mostly white residents of the suburbs) from the Rochester PD. That “game,” I suppose, is meant to stand in for the racial and economic segregation that characterizes the Rochester metro area. There is a garnish, but no more, of reference to underlying political-economic and racial complexities that generated this stereotypical view of urban America.”

Next week, I have the privilege of giving a talk at the Society for Photographic Education national conference in New Orleans. The theme of the meeting this year is: Atmospheres: Climate, Equity and Community in Photography. What the photo world – and even more so, the photo contest sphere/culture/atmosphere fails to address or appreciate is how much photojournalism is part of a larger social and interactive realm. All too often, photographers, publishers and editors seem to operate in a closed loop, primarily in a dialogue with their peers or the photo community, especially via social media. What that tends to supercede is how much they are part of a larger “media ecology” where engagement extends to the town/city/citizen/cultural group etc. that one chooses to depict. To the extent “the feedback” from Utica mostly stayed in Utica, or Rochester and Charleroi only come to light as photo contest “complication” doesn’t mean they are rare and incidental, and it doesn’t mean that the industry can ignore how these depictions mirror the community, often unrecognizably, to itself. Doing so only reinforces a false sense of security — and isolation.

A parallel trend to consider is how much photojournalism, including news photography, has upped the “artistic quotient” and become that much more interpretive and artistic form. If there has been plenty of discussion about this trend inside the “photojournalism space,” there has been very little of it in the context of how a more abstract and artistic documentary approach – one in which the depiction of gangbangs and sex in cars and obese people sitting in the dark or artfully posing in the dark again with guns — might be a concern to mayors or citizens of these town with access to this newfangled thing called the Internet.

A point I’ll be stressing next week is a reality the established news and photo media industry still seems largely oblivious to. That is, that the larger critical and deliberative space for still photography is no longer the publisher’s news site, but social media. Along those lines, the ultimate editor of press imagery is not someone sitting at a desk at a news corporation somewhere. That function, for better or worse, is conducted by public culture and mediated just as much by citizens who look at editorial photos like the ones above, including the World Press-winning photos from Belgium, and just don’t understand.

— Michael Shaw

(photos 1 & 2: Giovanni Troilo for Luz Photo. caption 1: Charleroi, Belgium The newest and tallest building in Charleroi is the 75-meter-high police station. Charleroi, a town near Brussels, has experienced the collapse of industrial manufacturing, rising unemployment, increasing immigration and outbreak of micro-criminality. The roads, once fresh and neat, appear today desolated and abandoned, industries are closing down, and vegetation grows in the old industrial districts. caption 2: Charleroi, a town near Brussels, has experienced the collapse of industrial manufacturing, rising unemployment, increasing immigration and outbreak of micro-criminality. The roads, once fresh and neat, appear today desolated and abandoned, industries are closing down, and vegetation grows in the old industrial districts. photos 3 & 4: Spencer Platt/Getty Images. caption 3: MAY 14: A former bank remains in disrepair on May 14, 2012 in Utica, New York. Like many upstate New York communities, Utica is struggling to make the transition from a former manufacturing hub. The city’s individual poverty rate is twice the national average with an unemployment rate of 9.8% as of February 2012. Citing Utica’s weakening financial margins over the past two years, Fitch Ratings downgraded its credit rating on Utica by two notches to a triple-B, two rungs above junk territory. caption 4: MAY 14: A child sits on a stoop in a working class section of Utica on May 14, 2012 in Utica, New York. (The rest of the caption repeats the previous one.) photos 5 & 6: Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum für ZEITmagazin. caption 5: An den Straßenecken verkaufen sie Drogen: Die “corner kids” laufen erst dann davon, wenn die Polizisten aussteigen. caption 6: Die Hauptaufgabe der Polizisten: Streit schlichten. Oft geht es um häusliche Gewalt.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus