Notes

Pictures Beyond the Veil: The Hijab and Free Choice

As Middle East politics works its way back into the foreground of the U.S. media’s truncated news frame, it should be no surprise that hijabs (and their permutations) have been in the news a lot. On the page or screen they act as a visual synecdoche (a figure of speech in which a part of something stands for the whole of that thing)—imagistic shorthand for fundamentalist Islam’s gendered tyranny. At issue is the question of (in)visibility. As women recede into increasingly more restrictive covering, their individual identities are obscured—traded for a prescribed homogeneity. That continuum was personified in 2010 by Yemini photographer Boushra Almutawakel, who posed with her daughter for a series of photographs entitled “Mother, Daughter and Doll.” The collection is being displayed at New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery as part of an exhibit called “The Middle East Revealed: A Female Perspective,” and select images were recently featured on the New York Times Lens blog:

Almutawakel hails from a prominent conservative family in Yemen, and her mother chooses to wear a niqab (a veil that displays only the woman’s eyes). Almutwakel told the New York Times that the photo spread displays the diversity of veils she encounters in her daily life when in Yemen, with the first three outfits belonging to her and the rest coming from her “mother, aunt, friends, and strangers.” Almutwakel makes clear that while she is not opposed to veiling, laws that either compel women to cover or forbid them from covering (as happened in France in 2011) are equally problematic. She urged readers to “just leave the women alone and let them decide for themselves what they want to do.”

While freedom of choice and self determination are paramount values for Almutawakel, her gallery articulates a clear editorial perspective. At the beginning of the continuum, Almutawakel and her daughter are smiling, and their modest yet colorful outfits allow expression of personal style. As the veils become darker and more expansive, a heaviness descends on the photos, dragging down the corners of the subjects’ mouths and rendering them as inanimate as the doll in the little girl’s lap. The inclusion of the doll in each photo was a brilliant choice. In the first few images, the distinction between human and doll is apparent. Later in the continuum, one would be hard pressed to say, for sure, whether or not the little girl is holding a doll or a baby. Almutawakel’s narrative is punctuated by the last image. The photo’s subject is no longer “mother, daughter, and doll”; it is the invisibility of women that results when they are denied freedom of movement and expression.

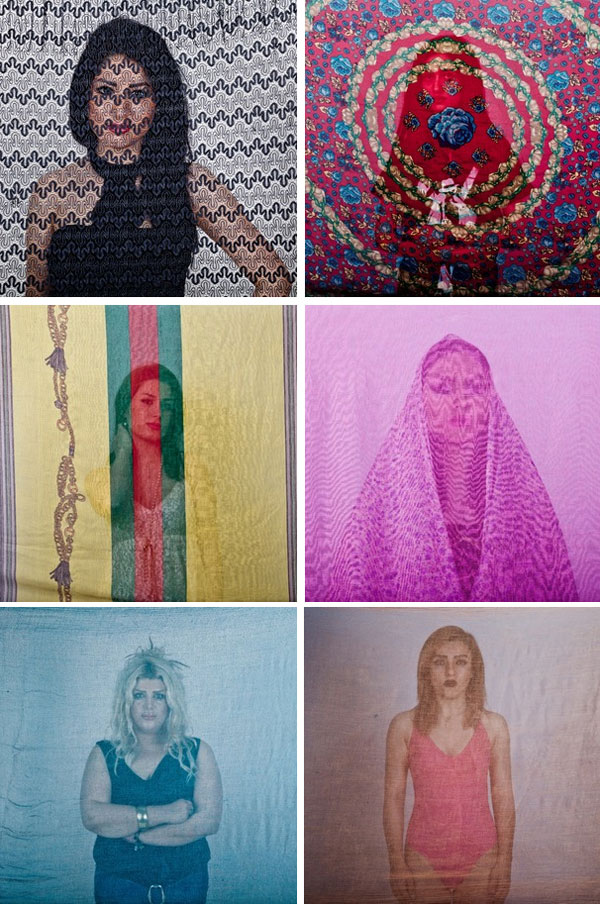

Although compulsary veiling is certainly a violation of women’s civil rights and a way to circumscribe their personal and political agency, the act of unveiling can similarly obscure women’s identities. Another recent NYT photo spread, entitled Veiled Truths, features photos taken by Iranian documentary photographer Hossein Fatemi. According to the New York Times, Fatemi says that he was inspired to create the collection after a female friend was detained in Iran for failing to wear a proper hijab. Although his friend urged him to “document what Iranians were experiencing in public life in a big city like Tehran,” Fatemi chose to stage photos of women and girls as seen through translucent veil material.

On the one hand, the images remind the viewer that beneath their veils, Muslim women are as diverse as all other women. In fact, effort seems to have been made to westernize certain images (the specter of Michael Jackson looms in one photo). The extent to which Fatemi’s images exoticize and sometimes sexualize their subjects reveals that the male gaze is not confined to Western culture. Iranian artist and writer Haleh Anvari published a NYT op-ed excoriating Fatemi and the Times for contributing to the fetishization of Iranian women and underscoring the problems associated with making veiled women a synecdoche for her country. Anvari explained that when she worked with foreign journalists, she “helped produce reports that were illustrated invariably with a woman in a black chador.” When she inquired why, her colleague responded, “How else can we show where we are?” Anvari’s sardonic response bears repeating here: “How wonderful. We had become Iran’s Eiffel Tower or Big Ben.” At issue in Anvari’s critique seems to be the question of authorship. If male photographers and editors are orchestrating the display of Muslim women, are their depictions authentic? The hubristic title that accompanies Fatemi’s article—“Veiled Truths”—seems to assert that they are.

But compare those photos with ones contributed by women to the viral Facebook page “My Stealthy Freedom.” Conceived by London-based Iranian journalist Masih Alinejad, the page invites women to contribute photos of themselves removing their veils in public. Despite the celebratory tenor of many of the photos, Iranian women who choose to participate are putting themselves at risk. Even Alinejad, whose London address keeps her out of the reach of Iranian clerics, has felt the wrath of state-sponsored backlash. She told Time magazine that the Iranian government fabricated a (completely untrue) story alleging that she was raped in front of her son and broadcast it on state TV as retaliation for the Facebook page. The tactic illustrates that the Iranian government still regards women as culpable for their own rapes—a sentiment that is used to justify draconian laws that restrict women’s freedom.

Despite the risk of public shame and state censure, however, women are participating in the “My Stealthy Freedom” campaign in droves. A cursory examination of the page’s photo gallery reveals women of various ages, shapes, styles, occupations, and perspectives demonstrating the infinite authenticities that constitute the female face of Islam.

Although it has been up for just a few weeks, the page has over 500,000 likes and hundreds of photo submissions. The photo that jumped out at me was this one—a young, Iranian soccer fan who used her nation’s flag as an act of celebratory resistance as she took part in a gathering that formed after Iran played Argentina last week in the World Cup.

This single amateur photograph captures the collision of topics in this week’s news cycle: Middle East politics, feminism, and World Cup fever. The photo is strikingly similar to one featured by Bag News in 2011:

In that photo, a French Muslim girl was using her country’s flag to protest laws that inhibited veiling. Whereas the French girl used her flag to cover, the Iranian young women used her flag to obscure her identity as she resisted compulsory veiling. Both photographs remind us of what’s at stake in this debate: women’s personal freedom and political agency. And they remind us of what is behind, beside, and beyond the veil: citizens and individuals.

By Karrin Anderson | @KVAnderson

(photo 1: John Moore/Getty Images caption: Women, dressed in traditional Islamic hijab, walk past the former home of the late Ayatollah Khomeini on June 3, 2014 in Qom, Iran. Iran is marking the 25th anniversary of the death of the Ayatollah Khomeini and his legacy of the Islamic Revolution.photo montage 2: Boushra Almutawakel photo montage 3: Hossein Fatemi photo montage 4: My Stealthy Freedom/Facebook photo 5: My Stealthy Freedom/Facebook. caption: Facebook caption: “My freedom was not stealthy.it was out in front all all [sic] the people.the people who, like me, poured out on to the street to express their joy and gratitude for the performance of the Iran’s national team.World Cup 2014: Argentina – Iran. (photo 6: AFP/Paris caption: A French Muslim girl using the country’s flag as her burqa.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus