Notes

Photographs of a Botched Execution Are as American as Apple Pie (GRAPHIC)

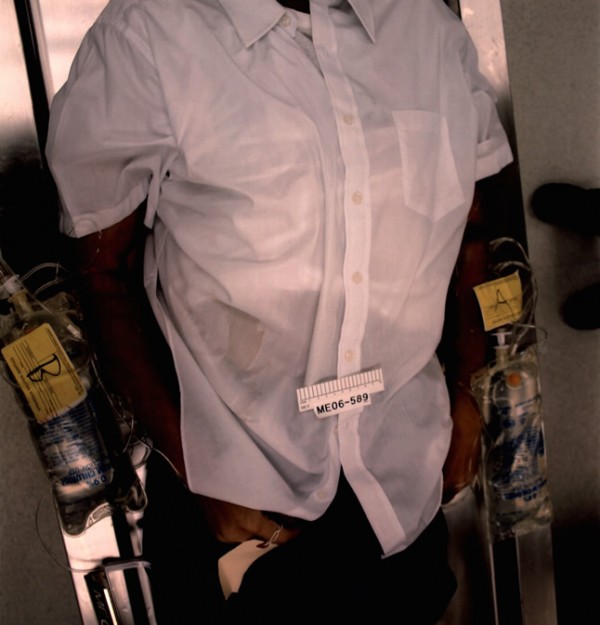

Last week, The New Republic published for the first time a set of photographs of a chemically burnt corpse. The body was that of Angel Diaz, a man executed by the state of Florida in December of 2006. As author of the piece, Ben Crair explains, “The execution team pushed IV catheters straight through the veins in both his arms and into the underlying tissue.” Diaz sustained horrendous surface and subcutaneous chemical burns.

“As a result,” Crair continues, “Diaz required two full doses of the lethal drugs, and an execution scheduled to take only 10 to 15 minutes lasted 34. It was one of the worst botches since states began using lethal injection in the 1980s, and Jeb Bush, then the governor of Florida, responded with a moratorium on executions.”

Known, but never seen

The photographs were made by a Florida medical examiner during Diaz’s autopsy. Crair discovered the photographs in the case file of Ian Lightbourne, a Florida death-row prisoner whose lawyers submitted them as evidence that lethal injection poses an unconstitutional risk of cruel and unusual punishment. While the details of Diaz’s botched execution have been known since 2006, this is the first time visual evidence of the injuries sustained from the lethal injection has been presented publicly.

I’d like to tell you that such images are anomalous, but sadly that is not the case.

I, myself, have seen a set of images of a burnt corpse post execution. The victim in that case was executed in the electric chair. Similarly, in that case, the images were in the possession of a lawyer (who had acquired them through family of the executed) and used in court in argument against the electric chair as cruel and unusual punishment.*1

May I suggest that the photographs of Angel Diaz’ corpse, and all those images like them, be accessioned into the Library of Congress? If the Library of Congress’ mandate is to preserve those things that are central to American culture; central to the American conscience, dear to this nation’s body politic and truly reflective of our culture, then I hold there is no better collection of images than these.

Between 1890 and 2010, the U.S. has executed 8,776 people. Of those, Austin Sarat, author of Gruesome Spectacles: Botched Executions and America’s Death Penalty says 276 went wrong in some way. Of all the methods used, lethal injection had the highest rate of botched executions — about 7%.

Photographs of a botched execution are as American as apple pie.

Whether an execution is considered officially “botched” or not, the torture imposed on a body in the minutes before death is unconscionable. Crair pursued the story and the publication of the images, rightly so, in the aftermath of the recent botched execution of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma.

“The execution team struggled for 51 minutes to find a vein for IV access,” writes Crair, “eventually aiming for the femoral vein deep in Lockett’s groin. Something went wrong: Oklahoma first said the vein had “blown,” then “exploded,” and eventually just “collapsed,” all of which would be unusual for the thick femoral vein if an IV had been inserted correctly. Whatever it was, the drugs saturated the surrounding tissue rather than flowing into his bloodstream. The director of corrections called off the execution, at which point the lethal injection became a life-saving operation. But it was too late for Lockett. Ten minutes later, and a full hour-and-forty-seven minutes after Lockett entered the death chamber, a doctor pronounced him dead.”

Closing the blinds

The single detail about the Oklahoma debacle that really stuck in my mind was the state’s decision — upon realising the execution was being botched — to drop the blinds.

The gallery of spectators including press, victim’s family and prisoner’s family lost their privileged view.

In that instance when the blinds dropped, the scene switched from that of official, public enactment of justice to the messy, sick, complicit torture of a human. In that instance, the barbarity of the state revealed itself fully. And the state was ashamed. The public were no longer allowed to see.

The notion — indeed the internal logic of the state – that viewing one type of execution is acceptable and another is not is astounding. By virtue of its actions during Lockett’s botched execution, the state has distinguished between what types of torture (execution) it is acceptable to see. Quick, quiet, seemingly painless equals good. Noisy, drawn out, demonstratively torturous equals not good.

The distinctions are petty. All executions are cruel and unusual.

At this point, I can only presume those who still support the death penalty are those who subscribe to some pathological eye-for-an-eye illogic. Wake up! The state shouldn’t be involved in murdering people. Especially when we have seen 1 in 10 people locked up for life or on death row for capital offenses later exonerated due to DNA evidence or prosecutorial misconduct. The state shouldn’t be involved in murdering innocent people.

— Pete Brook

(cross-posted from Prison Photography)

*1 People are under the misconception that the electric chair zaps a person and kills them instantly. This is not the case. Electricity takes the paths of least resistance which is outside of the body. Therefore, tens of thousands of volts serve only to burn the points at which they are attached, namely the lower leg and the skull. Death by electric chair is in fact just boiling the victims brain for 7 seconds. Boiling the brain alive.

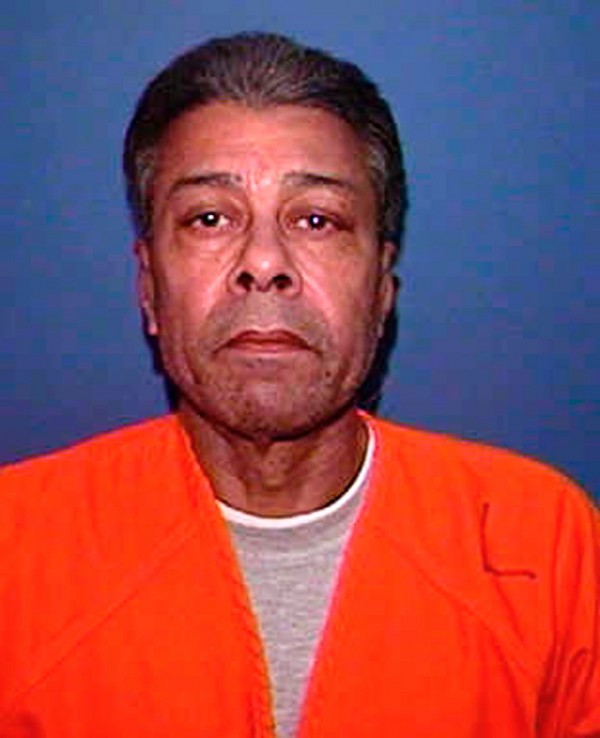

(photos 1-2: Florida Medical Examiner via New Republic. caption 1: Diaz’s body at the beginning of the autopsy, with the execution IVs still in both arms. caption 2: Diaz’s left arm had an 11-by-7 inch chemical burn from the lethal drugs. By the time the autopsy began, the superficial skin had sloughed off, revealing white subcutaneous skin. photo 3: Florida Dept of Corrections.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus