Notes

On the Move: 18 Visual Scholars Reflect on Previously Unseen JFK Assassination Photographs – #2

This is the second of three posts dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination. We invited a group of distinguished visual scholars to provide us with a brief response to photographs from November 1963. The images come from this unique set of photographs published at the New Yorker PhotoBooth three weeks ago. The anonymous photos, drawn from the International Center for Photography, were published for the first time. Here is a link to our series so far. You can find credits for each scholar at the bottom of each post. Click on each photo for full size.

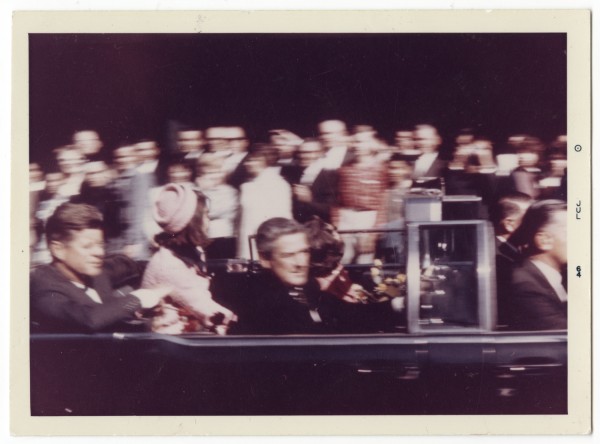

Governor John Connally, Nellie Connally, President John F. Kennedy, and Jacqueline Kennedy in Presidential limousine, Dallas. Unidentified photographer, November 22, 1963.

Marguerite Helmers

We know how this story ends. The fading of the photograph, the blurred background, the forward movement of the presidential limousine, all speak now to memory. At the moment this photograph was taken, only a few–perhaps one other–knew what would happen next, and even that was, even for Lee Harvey Oswald, a dark hope, a reliance on trained patience and a steady finger on the trigger.

Today, follow the gazes of the people in the limo and the people on the sidewalk. Everyone looks in a different direction. In this grand, moveable spectacle of the day, they aren’t sure where to look or what to look at. They are in the moment, with no idea of what happens next in this story. To us today, the assorted and unfocused gazes seem to presage what follows, not only in the moments following the president’s death, but in the approaching decades, as people seek not only the killer, but also, perennially, a truth–a focused and definitive story about the day.

Move now beyond the four figures in the limousine to the spectators on the sidewalk. We see a group of watchers to the right rear look off into the distance of the motorcade toward what is moving toward them in time and space. Focus now on the one man in a light blue shirt positioned just over JFK’s head. For this spectator, JFK is already in the past tense. While his body faces the president, he is already anticipating what is coming next.

Janis Edwards

What strikes me about these photos is the sharp difference between the everyday appearance of the JFK visit and motorcade, compared to the funereal photos in the next post. The presidential visit to Texas appears almost casual, sans the close crush of security, advisors, and even media. Of course, the limo had a safety bubble (not installed on this day), and one may assume that the assassination itself ramped up security in future years. But the mid-distance shots of the Kennedy party and the casualness of the open-air limo speak to quite different circumstances then enjoyed by presidential motorcades.

It almost seems as if the Kennedys and Connallys are parade marshalls, intended to be seen and greeted. The open atmosphere clamps shut, however, in the post-assassination photos. These are nearly indistinguishable from portrayals of presidential ceremony that are common today. Access is denied, formality is the style, and those who remain behind seem shielded, somehow. In that moment, it’s as if the relationship between the president and The People changed. Now, instead of Everyman, the presidential persona is heightened to a ceremonial level, distanced from the crowd. “Likability” is a factor of the presidential persona that now requires grooming, and is suspect, because we cannot experience our leaders casually any longer.

John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy, John Connally, and Nellie Connally in Presidential limousine, Dallas. Unidentified photographer, November 22, 1963.

John Murphy

President Kennedy’s most famous words–”ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country”–embody his life because they move. They imply reciprocity, an exchange relationship, one in which your country’s fate depends on you and your fate, in turn, is wrapped up in that of your community. To me, the first several of the pictures in the edit capture the motion, the elan of the Kennedy presidency. In the first, he reaches for the viewer’s hand, the one still locus of attention in an otherwise bustling scene, but in the rest he is on the move, flashing past the nation, much as did his short term in office. The pace, bustle, energy, and light then came to a close. The sequence of photographs poignantly strands in for the nation’s experience of his presidency.

Jennifer Mercieca

I’m struck by how the photos of JFK became instant nostalgia after his assassination (for example, the photo leading this post is marked with the date: November 22, 1963) and how today the photos still read as nostalgic. “Nostalgia” comes from the Greek (nostos: “homecoming” and -algia: “sickness”) and means something like a sickness from being away from home or a sentimental longing for the past. In 1963, the assassination of JFK created a kind of instant homesickness or sentimental longing for the optimism of Camelot. For modern viewers, this nostalgia is evoked and reinforced by the familiar, but antiquated, colors of the 1960s photography. Furthermore, I think that it’s interesting that modern photo filters allow us to create these same kinds of instantly nostalgic photos today.

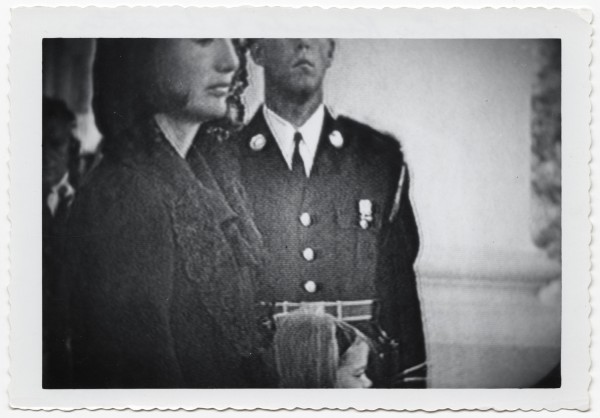

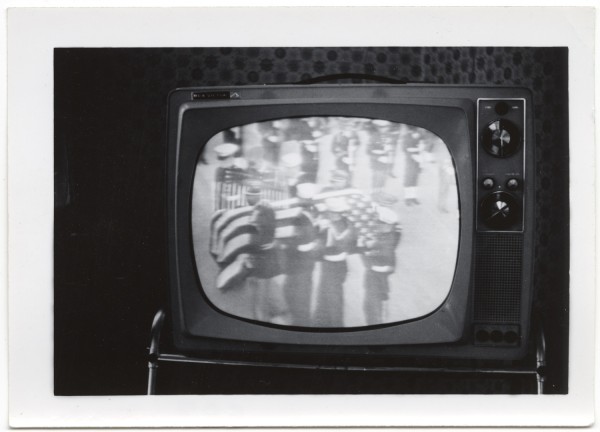

“Television image of Jacqueline Kennedy and Caroline Kennedy during John F. Kennedy’s funeral proceedings. Unidentified photographer, November 24, 1963”

Karrin Anderson

In her book Eloquence in an Electronic Age, Communication scholar Kathleen Hall Jamieson suggests that Ronald Reagan was the first U.S. president to capitalize on the “intimate style” of television for rhetorical effect. This photo, taken of the televised broadcast of John F. Kennedy’s funeral, illustrates that viewers recognized the intimacy of the televisual sphere long before Reagan’s tenure as president. Television enabled the nation not only to witness J.F.K.’s funeral but to experience it alongside the Kennedy family. Although the framing of this photo obscures the service member’s gaze, one presumes that he is looking stoically ahead. The gaze of the viewer of the broadcast (and subsequent photo), however, is drawn to Jacqueline and Caroline Kennedy, positioned close enough to see—or wipe away—any tear that might trickle down their faces. The photo typifies the ways in which meta-imaging (images of images) would come to characterize modern and postmodern political culture.

Next Up: Wendy Kozol, Christa J Olson, Jon Simons, Anne Demo, Brian L. Ott, Michael Butterworth and Robert Hariman.

See the rest of the series here: Visual Scholars Analyze JFK Assassination Photos

————————-

Marguerite Helmers is Professor of English, University of Wisconsin Oshkosh and Editor, Parlor Press Visual Rhetoric Series. She is the author of The Elements of Visual Analysis and Defining Visual Rhetorics with Charles A. Hill. Twitter: @aossidhe

Janis Edwards is Associate Professor of Communication Studies, University of Alabama. She is at work on a book about visual images and contemporary politics in the U.S.

John Murphy is Associate Professor of Communication, Dept. of Communication, University of Illinois. Twitter: @MurphyOA.

Jennifer R. Mercieca is Associate Professor & Associate Department Head, Department of Communication, Texas A&M University. Twitter @jenmercieca.

Karrin Vasby Anderson is Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Communication Studies, Colorado State University. She is also a frequent BagNews contributor. Twitter @KVAnderson.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus