Notes

Rita Leistner: Looking for Marshall McLuhan in Afghanistan #3 – The Life after Death of Skeuomorphism

“All media are extensions of some human faculty—psychic or physical”

(Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects)

Correction:

In my last dispatch, I referred to language as “man’s oldest technology.” It was pointed out to me (in a thoughtful comment) that, technically, language is not a technology. When I thought about it, I realized that not only is language not really a technology (it is, more accurately, a “medium”), it certainly wasn’t as old as a lot of other things humans have invented. Toolmaking, for instance, pre-dates speech-based societies by something like a million years (it’s not every day you can get your facts wrong by a million years). So how old is language? I wondered. And what exactly is it, if not a technology? When did the Homo species first move beyond grunts and shrieks to being able to utter vowels and consonants, and further, to compose complex syntactical structures and conditional phrases? For answers I consulted Steven Roger Fischer’s A History of Language (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 1999, pp. 35-60).

Language is an Extension of the Larynx

Fischer explains that the way we know when homonids first began speaking is by their migratory movements, “because they had elaborated, through rudimentary speech, a higher degree of social organization which enabled group migration” (Fischer, p. 38). Before that could happen, they had to develop the anatomical capabilities necessary to forming articulate utterances. Fischer describes it as the stage at which the larynx dropped in the throat (something that even today only happens in humans after about one to one and a half years of age) (Fischer, pp. 37 & 39). Fischer’s forays into the histories of talking apes are a prelude to the Afro-Asiatic root from which sprang the Proto-European, West Semitic, Indo-Iranian languages, among others, that we know today.

Speech alone does not constitute language. Language, as we understand it, is semiotic—symbolic, not purely associative. In other words, we don’t need a picture of a banana![]() to understand the idea “banana” as represented by the letters or sounds b a n a n a, or, for that matter, we don’t need a picture of a mechanical camera to understand that a smartphone can take a digital photograph.

to understand the idea “banana” as represented by the letters or sounds b a n a n a, or, for that matter, we don’t need a picture of a mechanical camera to understand that a smartphone can take a digital photograph.

“An indexical association—that is, a link between a physical object and a spoken or signed word like ‘banana’ or ‘keyboard’—is not symbolic, but simply associative” (Fischer, p. 45). In graphical interface design (an example is the iPhone Hipstamatic app) there is a word for this: “skeuomorphism.”

The Life after Death of Skeuomorphism

Skeuomorphism: [Greek: Skeuo “tool” +morph “shape”] An object or feature which imitates the design of a similar artifact made from another material. This definition comes from Oxford dictionaries.com. Not surprisingly, none of my “book object” dictionaries (I have a bunch) include the word “skeuomorphism.”

I was trying to find out more about Apples new iOS 7 when I first came across the word “skeumorphism” in a September 19 article called “A Eulogy for Skeuomorphism” (see Claire Evans, “A Eulogy for Skeuomorphism,” in Motherboard, June 2013; and http://www.apple.com/apple-events/june-2013). We all know what the word means and see examples of it every day but I couldn’t help but wonder how I had never heard of it before. In fact I’d just been writing about the “idea” skeuomorphism in my new book (“Looking for Marshall McLuhan in Afghanistan,” Bristol: Intellect Ltd. and Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2013, p. 106). But I’d described it like this: “The Hipstamatic app is an attempt to reclaim the loss of mechanical photography within the digital medium. The look of the app on the iPhone (with absolutely no functional value) is a virtual-mechanical camera. The “shutter” is represented by an image of a button that you press with your finger—the only “digit” left in digital.”

I thought about contacting my publisher with a last minute correction so that it wouldn’t seem like I’d missed out on the most useful word of the year. But after a while I came to see the word skeuomorphism as a kind of advertising ploy. I even took an informal survey among my noted designer friends to see if I was the only one who had never heard this word before (an architect, two graphic designers, a chair designer, an illustrator and a typography designer) and all but one, like me, had never seen the word “skeuomorphism” until recently. The one who had heard the word before was a graphic designer who remembered it from a lesson back in design school in the 80s.

At first I thought it was ironic that a new word would be dug up, popularized and brought into usage only in order to announce the obsolescence of what it describes. But it’s just a sign of our times to try and shrink the time between action and reaction so much that they seem to happen in reverse.

In the 1960s, McLuhan coined the expression The Global Village to describe the scope of change and dissemination of information in the electric age of television and radio. Today, the Global Village is on speed and smartphones are our most ubiquitous amphetamine.

Printed Images and Words on Paper (aka, books)

The permanence of the printed image has been exchanged for a transient digital image that most users never intend to preserve on paper. They are meant to be traded and communicated to others, like phone calls: photograph as transmission of information, not as material object.

We have come a long way from and back again to the words of William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the fathers of photography, who, nearly 200 years ago, said of the light images projected through the lens of a camera obscura:“How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed on paper” (William Henry Fox Talbot, c.1820, in The Pencil of Nature).

There is something similar but different about the experience of looking at an image of oneself on the back of an iPhone (or any digital device) compared to holding a photograph of oneself in one’s hands. The first portrait photography was viewed as a kind of fixed mirror image. It drew analogies to the myth of Narcissus, as described by McLuhan:“Men at once become fascinated by any extension of themselves in any material other than themselves”(Marshall McLuhan inUnderstanding Media: The Extensions of Man).

We look at images of ourselves on the backs of digital devices as if looking into mirrors because the instantaneity of the moment gives over to the feeling of looking at ourselves “as we are.” I saw this among Afghan children who looked at pictures of themselves on the back of my iPhone with curiosity (and usually delight), with no expectation that the image would ever be more than the shiny frozen-in-a-second picture that seems to live inside the box.

It feels subversive to take images shot on an iPhone and hoick them out of the safety of their little black device (the digital womb) into the outside world to be printed with ink on paper. They were born, after all, to flow freely from phone to phone or across social media networks, to be taken and looked at and perhaps never looked at again—almost as ephemeral and transient at the light images cast by the camera obscura, as impermanent as reflections in a mirror.

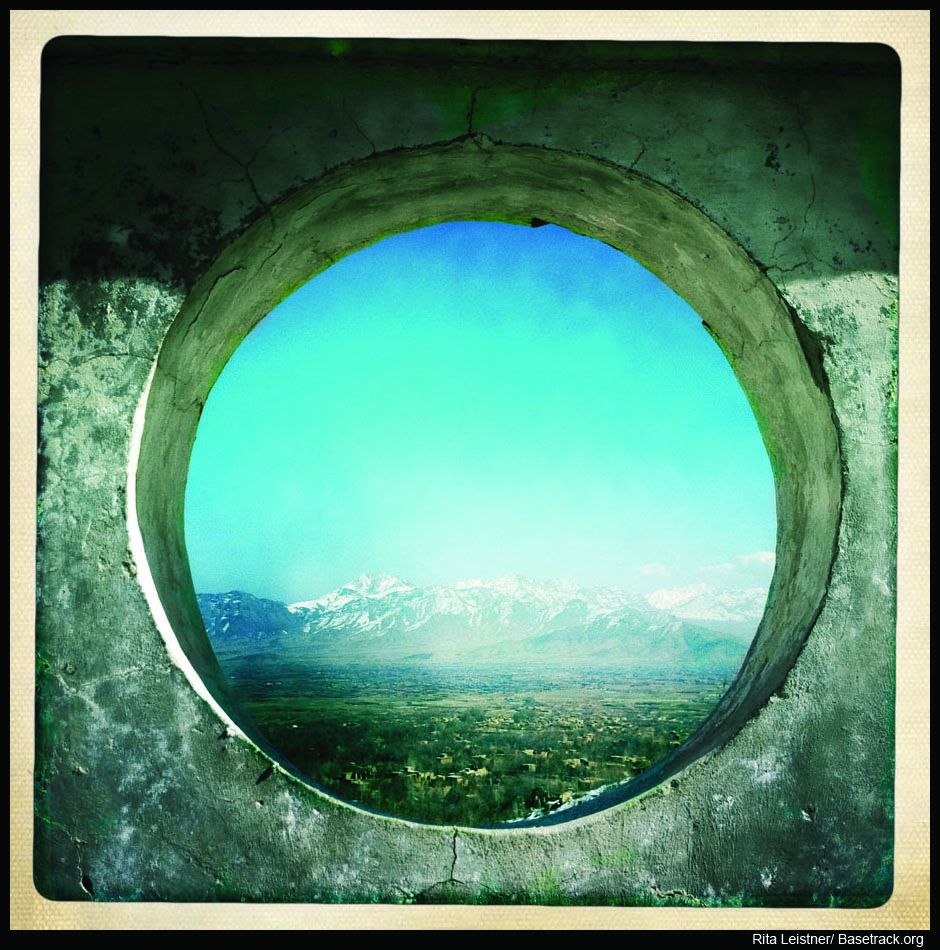

For the first time in history we are making photography and writing on the very same tool. The affected and algorithmic images of the smartphone draw attention to the devices they are made on, and for me, at least, have opened a portal between image and text that I believe we have only just begun to explore.

Rita Leistner

October 18th, 2013

END

Text and PHOTOGRAPHS by Rita Leistner

This is the third installment in the series, Looking for Marshall McLuhan in Afghanistan. You can find the other two here.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus