Notes

James Whitlow Delano – Second Dispatch: As the Rainforest Goes, So Go the Batek?

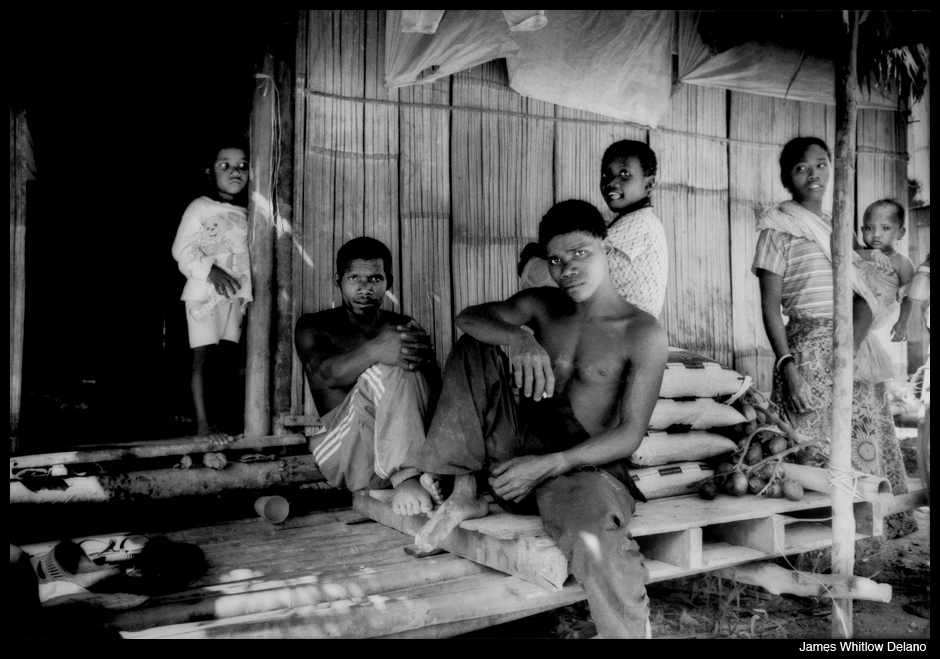

An extended Batek Negrito family living in a squalid, tree-less camp set aside by the Malaysian government beside the entrance to Taman Negara National Park, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia. The harsh, infernal nature of the government settlement has meant that this community of Batek Negritos has split into two groups, this one which engages in the cash economy and one that lives a semi-nomadic existence and much more upon the fruits of the rainforest. Almost all the land north of the park, their traditional homeland, has been clear cut and converted to oil palm cultivation. Much of that oil will be used to make bio fuel.

The morning air in Gua Mustang was surprisingly cool. Towering trees covered limestone karst mountains, the same kind made famous in Guilin, China, that rise at the end of main street beyond the tracks that carry the so-called “jungle train” through town.

Nowadays “jungle train” is a bit of a misnomer, the “oil palm” train would be more accurate. Gua Musang is the gateway to the northern entrance to Taman Negara National Park, Malaysia’s oldest and largest national park. North of the park also used to be a massive forest but it has all been clear-cut beginning in the 1970’s and converted to oil palm plantations, which is a big part of how Malaysia has become #2 in the world behind its larger neighbor, Indonesia, in its production. It also used to be part of the ancestral forest of the Batek Negrito people. They now live huddled up against the northern boundary of the national park, a massive 1,677 sq miles (4,343 km²) forest that the government would rather they not enter.

On this first trip to contact the Batek in 2010, I stayed inside the national park at Kuala Koh, which meant waiting for a four-wheel drive from the national park to come pick me up for the 2 hour drive through the palm oil plantations to the park compound. I would get to know this mostly paved road well later on for its oddly treacherous character. Malaysia’s roads are remarkably good but for that reason, and heavy traffic from trucks loaded to the top with oil palm fruit, this relatively well-paved road was pocked marked at odd intervals with deep, solitary tire-puncturing potholes.

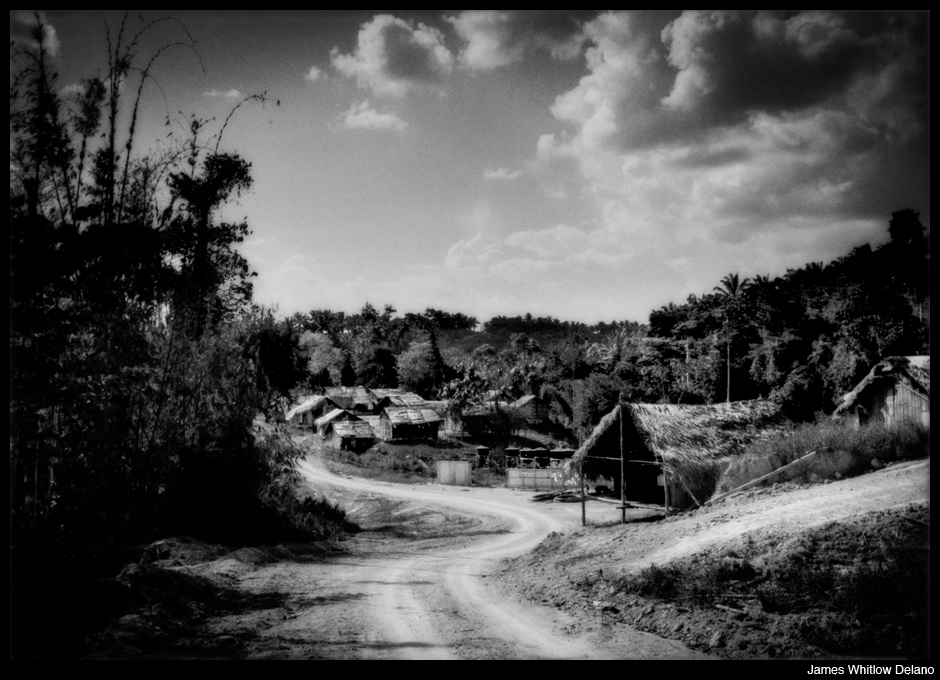

Barren Batek Negrito settlement set up by the government outside the entrance to Taman Negara National Park, sandwiched between the great protected forest and vast oil palm plantations to the north that now occupy land the Batek would live in and wander through when it was clothed in old growth rainforest not so long ago, Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia.

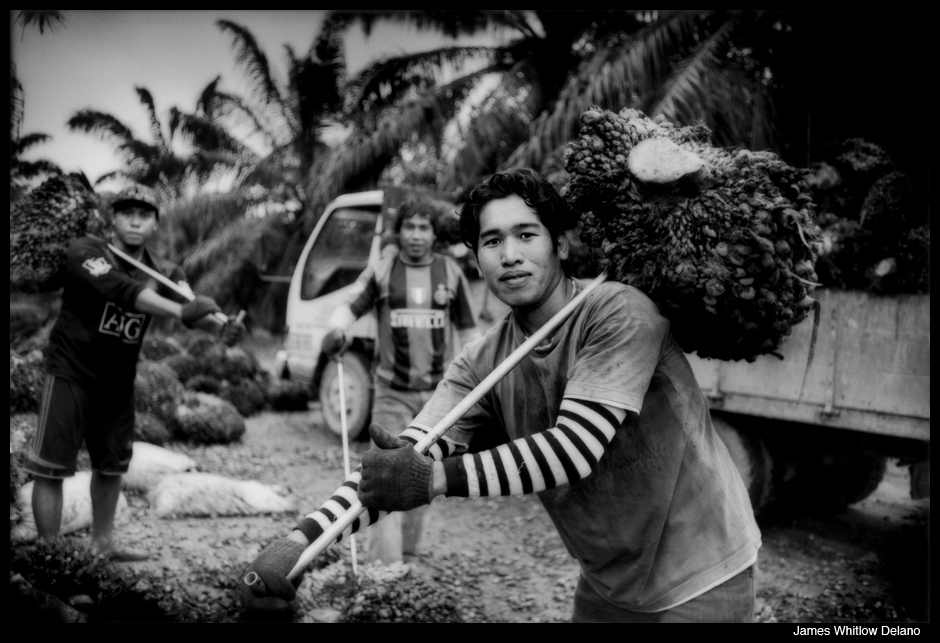

This time, Wan, a park employee, would ferry me through vast, continuous plantations, stopping to ask me to be an accomplice in his theft of a cluster of oil palm fruit. Pulling over on a lonely stretch and checking that the coast was clear, Wan hopped out and motioned for me to help him hoist a heavy, oily red-brown fruit cluster, shaped like a gigantic bunch of grapes into the back of the truck before covering it with a tarpaulin. He said that it was great fish bait, and apparently the forest elephants eat it like candy. Getting back in the truck, I noticed my shirt had been absolutely coated with grease from the oily fruit.

Unsustainable aged oil palm plantation is cut down to rid it of “senile” trees and replant with younger more productive trees at the edge of what used to be the Batek Negritos homeland. There is no is no place for forest-dwelling peoples in the Malaysia development model set in motion a couple of decades ago by former PM Mahathir Mohamad. Kelantan State, Peninsular Malaysia. (2011)

No map or signpost was needed to know when one crosses into the park. A squalid government-sanctioned Batek settlement had been built right at the park’s edge, which is clearly scrawled in natural forest, where it meets the plantation. Under the oil palms, only grass and a few ferns grew atop the red, inorganic subsoil, littered with cow manure by grazing cattle.

After settling in, I casually inquired about visiting the Batek settlement with national park staff but was met with vague deflections like, “you cannot visit them now, their headman is outside the area for a few weeks.” Environmental and indigenous peoples’ rights issues can be particularly controversial in Malaysia, especially if they are seen by the government as impeding the nation’s development. I communicated with a young German anthropologist in the 1990’s, who was prevented from re-entering Malaysia for publishing a damning report about another clan of Batek living near the national park headquarters in the south under squalid conditions, and forced to endure a daily procession of park-organized tours through their camp. So, by the third or fourth evasive park official’s response, I decided it was better to quietly slip away on my own.

I walked a mile or so out along a paved road through the forest back out to the Batek settlement. Soon I arrived at a treeless parcel of land beside the park entrance. The Batek had built a dusty collection of raised bamboo huts, with some motor bikes and a car or two parked nearby. For at least two generations, the Malaysian government has been attempting, and largely failing, to lure the Negrito peoples out of the forest into the “modern” world.

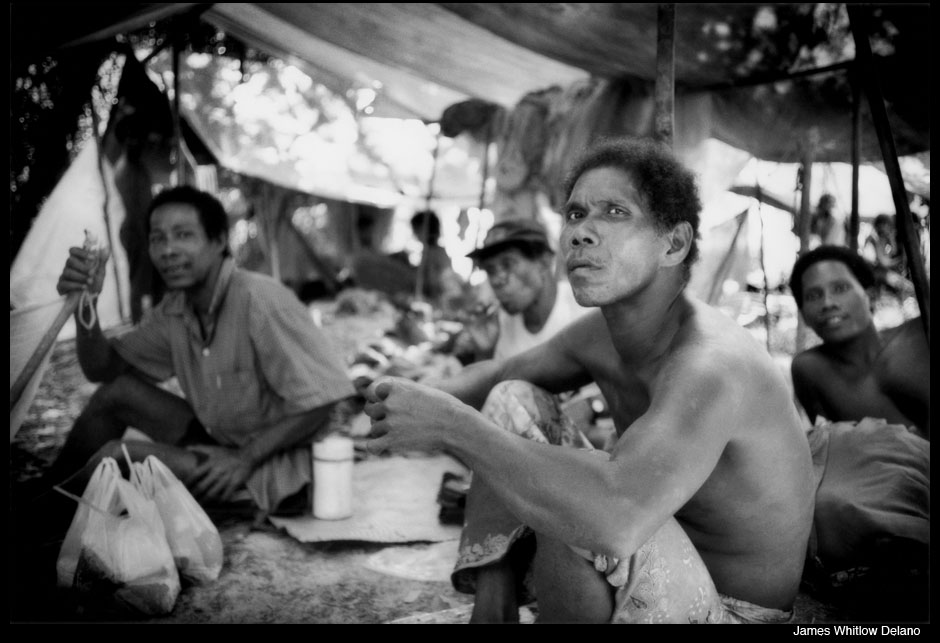

Indigenous Negrito day labourers take shelter beneath Seri Gemilang Bridge from a passing rain shower. For the past three decades, the Malaysian government has actively sought to bring the nomadic, hunter-gatherer Negrito peoples into the settled mainstream Malaysia society. Logging of their native mountain rainforests has made it necessary to take on unskilled labour jobs to feed their families. The Negrito possess unparalleled knowledge of the medicinal and edible plants which grow in the oldest rainforest in the world. Outside the forest, Negritos are reduced to impoverished manual labourers, Putrajaya, Malaysia. (This photo was taken on a previous trip, in 2005)

Workers harvesting the fruit from oil palms, on the former homeland of the Batek Negritos, that will be refined into oil, much of which will be refined into “green” bio-fuel. These workers are ethnic Malay, though perhaps the majority of workers on oil palm plantations are ethnic Tamils (Southern Indians who came to Malaysia during the British colonial era). A few Batek Negrito men earn hard cash performing unskilled day labor on oil palm plantations. North of Kuala Koh, Kelantan, Malaysia. (2011)

The central government cannot abide by the embarrassment of having people still living in the forests of this Asian tiger. Economic necessity has meant, however, that about half of the Batek men are now living on the cash economy and the other half have chosen to try and subsist on the forest, creating the growing rift in Batek society between those who opted for their traditional response of pulling away from the outside world and those now engaging with it.

Despite the presence of a road, I still felt a sense of entering another, Batek, world, which is rare sensation nowadays. Asia can have a wonderland quality, where various waves of human migration have left magical pockets of peoples far from where you’d expect to find them. In a sea of straight, black-haired East Asians live the wooly-haired Batek, the men barely 5 feet tall and looking so African that I actually had a hard time convincing a man from Gabon one time, that the people in the photos I was showing him lived in Malaysia, not Africa.

A typical settlement, the Batek Negrito live in temporary, rudimentary shelters that are easily abandoned, except that polyethylene sheeting has largely replaced palm thatch and cotton clothing has replaced clothing from plant materials.

With the Batek, however, this may all be coming to an end. I was mingling with one of the oldest tribes of humanity and they may vanish before most of the human family even know that they had ever existed at all. It may sound heady, but I am honestly trying to do my part to prevent this from happening. In 2010, Boa Senior, the last speaker of the Negrito Khoro language in the Andaman Islands, cousins of the Batek, died. For the last 30 -40 years of her life, she had no one to speak to in her native tongue. That is what I am talking about, not something abstract but the real possibility of the extinction of a people. The Batek are one epidemic, or a generation of forced assimilation away from the fate of the Khoro.

Also see the first post in the series: James Whitlow Delano – First Dispatch: Return to the Rainforest

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus