Notes

Detroit, Braddock and the (Powerfully) Indeterminate Nature of the Image

Thinking a little more about Detroit’s recent filing for bankruptcy (by an unelected ‘emergency manager’), and the broader demise of industrially-linked urban communities, it’s interesting to note how in this 2010 Levis advert, whose imprecation seems to be to ‘go forth’ and rebuild dressed in the beautified and careworn attire of Levis goods themselves, labour is equated with an effort to reconstruct outside of any discernible political critique. The effort to rebuild Braddock, PA is instead rendered as an essentially biblical act, in a tone powerfully underscored by the use of the ever-ascending transfigurative music of Wagner, which was used in a similar way set to similar imagery at the beginning of Terrence Malick’s The New World.

The precursor to the advert, and in a sense its legitimating event, was the decision in October 2010 by Levis to send its employees to Braddock and engage in an effort to scrub places clean of decay, revitalise neglected community spaces and ‘get to know’ some of the people of the town. The present conditions of the city or its community are treated as apolitical and ahistorical, as somehow spontaneous, natural and uninflected by the specific dynamics of race relations, economic policy or uneven political representation. Since these specific complexities are unincorporated in the narrative in any form, the impetus to rebuild is made to seem both logical and virtuous, and so too by extension is the brand who sponsor the narrative that crystallises the idea.

LaToya Ruby Frazier has enacted performance pieces and made a large body of work dealing with the historical and political complexity of the present conditions of Braddock, not to mention the long genealogy of injustice that has underpinned the steady disassembly of the town. Her performance piece on the Levis campaign outlines a broad array of these concerns. Among the many interesting questions arising not only from this particular campaign, and Ruby Frazier’s rejoinder, but from the ever more pervasive normalcy of postindustrial devastation and political abandonment, is the role being afforded to art and to artists in depicting, interrogating and contending with the aftermath of these interwoven policies and histories. This is a development that the recent documentary Detropia dealt with in often problematic ways, and in a sense it is one that will again be raised by the forthcoming film Out of the Furnace, which was set within and largely based on the town of Braddock.

One thread that runs throughout these differing advertisements, performance pieces, documentaries and films is the central figure of labour, and the moral complexities that arise when dealing with the systematic and long-term dismantling of meaningful opportunities for work. The elevation of labour on aesthetic grounds to fashionable status is of course deeply tied to the history of Levis jeans, and perhaps one of the troubling questions that arise when thinking of the intersection of art and politics in communities suffering the neglect that has gone hand in hand with the process of de-industrialisation is the ease with which the aesthetic of labour can be deployed, in the absence of a context that questions its enormous political significance, or the history of uneven opportunities and freedoms that have been provided by industry. In art, or photography, this complexity has had to do with what Abigail Solomon-Godeau has called “the assimilation of post-modernist strategies back into the mass culture that had in part engendered them,” a dynamic that is well illustrated within the Levis campaign itself, where the aesthetic of realism and the symbolism of labour are appropriated by a multinational corporation with a dubious and problematic historical relationship to labour standards and worker’s rights.

Plainly the image by itself is incapable of resisting either its own commodification or political co-optation, and furthermore it is difficult to assign to art the role of producing, or the credit for realising social and political change – something that is in the end always the result of human efforts, and not reducible to the content of specific images.

What seems interesting to me is the way that the Levis campaign served as the trigger for a creative response that aimed at stimulating dialogue and substantive engagement, and that did so on grounds that are as equally political as they are aesthetic. If films like Detropia or Out of the Furnace can serve or can be made to serve similar functions, then perhaps these images can fulfil the role imagined by Ariella Azoulay in her work The Civil Contract of Photography, where she states that:

“from its very beginning, photography has been a mass medium that violently and rudely fixes anyone and anything as an image in ways that resist finalized determinations and that invite the participation of others in the negotiations of what and how that images signifies.”

This sort of a reading of the photographic image rests on a belief in the intrinsic value and irrepressible presence of a deeply social function to subjectivity. The indeterminate nature of the image guarantees that it can offer itself up as a ground on which to engage, socially, intersubjectively, one with another, in a reciprocal negotiation around the complex questions of identity, community and history, which is both invoked and suspended by the photograph. In precisely the same way that photographs depicting the abjection of slavery can be turned against the intentions of their makers, this suspended invocation of history presents us with an opportunity to question its inevitability, to dissent from its apparent normalcy.

The rise of industrialisation was trumpeted as the the forward march of progress, and thus the savage irony visible in images of de-industrialsed towns is most painfully clarified by the sense that history must therefore have abandoned them. Read in the way Azoulay suggests however, such a predicament cannot be made to seem inevitable. This sort of interpretation of the photographic image suggests a role that has at least the strong possibility of being democratic, and that offers the virtue of being perpetually open to an intersubjective negotiation between any group of people over how and why and on what terms we understand ourselves to be who, and where and what we are. In essence, it is an argument that holds that resistance begins first in the imagination:

“An opposition to history may be partly an opposition to what happens in it. But not only that. Every revolutionary protest is also a project against people being the objects of history. And as soon as people feel, as the result of their desperate protest, that they are no longer such objects, history ceases to have the monopoly of time.” – John Berger, “Appearances.”

— Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa

(cross-posted from the Tumblr blog, agreatleapsideways)

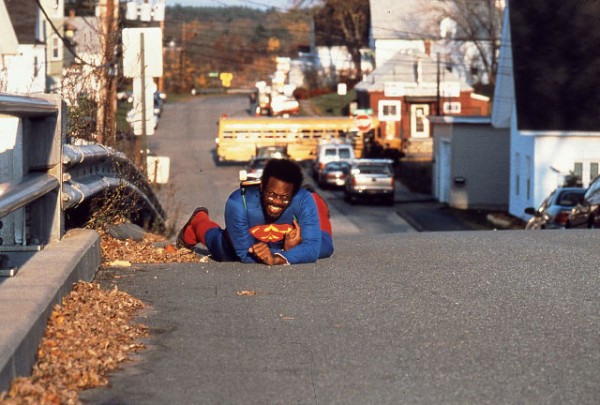

(photo: William Pope L. performing The Great White Way: 5 years, 22 miles)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus