Notes

James Whitlow Delano – First Dispatch: Return to the Rainforest

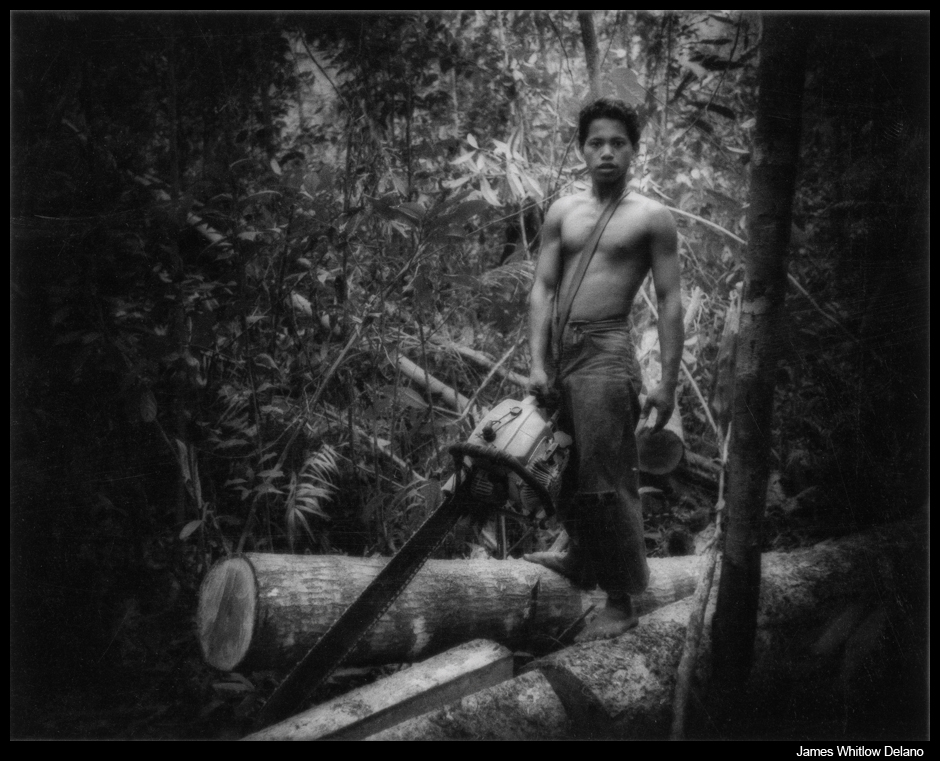

Illegal logger inside Gunung Palung Nat’l Park. This national forest is one of the last protected refuges for orangutans. This young man had been lent a chainsaw on behalf of the merchant in town who sells the timber. Illegal loggers have penetrated deep into the park. This was photographed on a five-hour hike into an orangutan research center within the park, four hours of which were through illegally logged forest. West Kalimantan (Borneo), Indonesia.

Illegal logger inside Gunung Palung Nat’l Park. This national forest is one of the last protected refuges for orangutans. This young man had been lent a chainsaw on behalf of the merchant in town who sells the timber. Illegal loggers have penetrated deep into the park. This was photographed on a five-hour hike into an orangutan research center within the park, four hours of which were through illegally logged forest. West Kalimantan (Borneo), Indonesia.

Over the months ahead, I want to make some sense about how a long- term project on the needless destruction of the equatorial rainforest came to be an obsession and how I have attempted to visually portray this form of daylight robbery. I also hope that a few good nuggets of advice can be carried away from these dispatches.

I visited Borneo for the first time in 1994, during the climax years of industrial logging. Arriving with a head full of 19th century accounts of the island only intensified the impact of rambling up an absolutely anaerobic, silt-choked Rejang River perched on the roof of a high-speed express longboat.

Alfred Russel Wallace, English naturalist and Darwin-contemporary, penned this simple description of Borneo in the 1850’s: “For hundreds of miles in every direction a magnificent forest extended over plain and mountain, rock and morass”. The mental picture of that place and time, where people were utterly irrelevant, had firmly taken root in me.

Agitated orangutan in the rainforest canopy, Interior Sarawak (Borneo), Malaysia. The orangutan broke off branches which it threw down upon intruders, fearing that the party were hunters. This forest, upstream from the Batang Ai Dam, remains one of the very few swathes of forest untouched by loggers for fear that logging debris washed downstream would jam hydroelectric turbines.

Agitated orangutan in the rainforest canopy, Interior Sarawak (Borneo), Malaysia. The orangutan broke off branches which it threw down upon intruders, fearing that the party were hunters. This forest, upstream from the Batang Ai Dam, remains one of the very few swathes of forest untouched by loggers for fear that logging debris washed downstream would jam hydroelectric turbines.

So, late 20th century reality stuck like a hammer blow to the temple. Rafts of hundreds of logs pulled by tugboats floated past, as the express longboat, though constantly on the look out, resonated like a tom-tom every time it struck an undetected, submerged log. Lower down the river there had been massive, smoke-emitting timber mills where trees were of so little value that they had been used as foundation filler for the riverfront docks where barges, piled high with more dead trees, were secured. Upriver the mills gave way to tugboat moorings so that tractor-trailer logging trucks, overburdened with freshly-cut timber, could come down from the mountains and efficiently dump logs into the current to be lashed together and floated downriver, guided by tugboat, to the sawmills. Either that, or the unprocessed logs could be loaded directly onto ships for export to Japan or Korea without adding any value to the Malaysian economy. Today, China is the number one destination though it is remains illegal to export unprocessed logs.

Borneo looked more like Bayonne, New Jersey than the impenetrable jungle of Dayak headhunters I’d hoped to explore. Extinguished forever was any romantic notion of equatorial Asia. Frankly, genocide is one of those words too easily bandied about but what I was witnessing was a cultural genocide in less than one generation waged for profit against these indigenous peoples.

Tugboat tows a barge full of Borneo timber past Kapit on its way to sawmills down the Rejang River. Sarawak, Malaysia.

Tugboat tows a barge full of Borneo timber past Kapit on its way to sawmills down the Rejang River. Sarawak, Malaysia.

The scale of permanent damage was simply breathtaking. So, I wondered, how could anyone visually represent the scale of this human-made debacle in a way that would make sense to people halfway around the world, who would probably never come to Borneo; or was it such a fait accompli that it would simply be a botanical and cultural post mortem examination?

Being self-funded, I recorded what I could afford to, by stealth, all the way to the Kalimantan (Indonesia) border. Over two trips, however, I was so disheartened by what I had witnessed (and so distracted by the rise of China), a decade passed before I was drawn back. Precisely what (or I should say, who) drew me back were two indigenous peoples, one in Borneo and another on the Malay Peninsula. The Penan people, I was surprised to learn in 2010, were still erecting rickety barricades in the last inhabited corner of the Malaysian state of Sarawak on Borneo that loggers had not reached. I thought the Penan had given up the ghost at least a decade before but, after 30 years, they were still passively resisting the loggers. Unfortunately the loggers, whose clear goal was to fell every valuable tree in Sarawak that stood unprotected outside a national park, also hadn’t quit. To that end, they have been largely successful.

The others were the last of the Batek Negritos of the Malay Peninsula, some of the first people to walk out of Africa probably 60,000 years ago and still looking every bit as African as if they just left yesterday. Standing before them, tall-nosed and pink, it was hard to believe that my own ancestry was much closer to Africa than theirs were, but my ancestors had walked north and had changed outwardly to adapt to a frigid climate.

When I first came to Asia, I prided myself on knowing things here that very few people in the West did. This time I would tap into lessons learned. I knew I had to find a way to palpably connect a viewer in New York, Paris, or Tokyo to events in far away Malaysia. I needed to connect those readers to the indigenous peoples who most fascinated me or the message would fall on deaf ears. I sat on this plan until the moment was right. That moment came when the massive Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico hit global headlines and the topic of alternative energy sources, including bio-fuel, popped into the media cycle, and stayed there.

Logging port on Borneo’s Rejang River, Malaysia. Piled high upon the banks of the Lower Rejang River, timber is so plentiful it was used to construct the actual boat landing. Sarawak (Borneo), Malaysia.

Logging port on Borneo’s Rejang River, Malaysia. Piled high upon the banks of the Lower Rejang River, timber is so plentiful it was used to construct the actual boat landing. Sarawak (Borneo), Malaysia.

Not only were the indigenous peoples of Malaysia losing the forest they have subsisted on for their entire history but, after loggers irreparably ravaged their forests, oil palm plantations were planted on that land, often by subsidiaries of the same corporations that had cut the forests down.

These corporations had hatched a brilliantly simple plan. Lawyering up against the politically weak locals would allow them to legally harvest the “green gold” on the surface from indigenous peoples’ ancestral forest and then profit in perpetuity by way of the oil palm plantations. Better still, because bio-fuel had been widely accepted as a sustainable, carbon-neutral alternative to petroleum, these exploitative corporations attempted to also don the mantle of being “green.” Some, in fact, even attempted to pass off of this planting of oil palm, a cash crop, as reforestation.

Truck laden with gigantic logs raises dust on a private logging road deep in the interior of Borneo. A decade ago this forest was untouched wilderness a day’s walk in from the last upriver longhouse, 2 1/2 days by longboat from the market town of Kapit up the Sungai Gaat River. Sarawak (Borneo), Malaysia.

Truck laden with gigantic logs raises dust on a private logging road deep in the interior of Borneo. A decade ago this forest was untouched wilderness a day’s walk in from the last upriver longhouse, 2 1/2 days by longboat from the market town of Kapit up the Sungai Gaat River. Sarawak (Borneo), Malaysia.

I can feel my blood pressure rising again simply writing about it. This is like cutting down the redwoods, planting an apple orchard and then calling it even. The deeper I dug into their business practices, the higher the hypocrisy piled up. I wanted to show, not just tell, how our consumer habits directly aided in the cultural genocide perpetrated against the inhabitants of a 100 million year old ecosystem. The time to return to the rainforest had come.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus