Notes

Before and Before That: Alexandra Boulat and the Iraq War Ten Year Anniversary

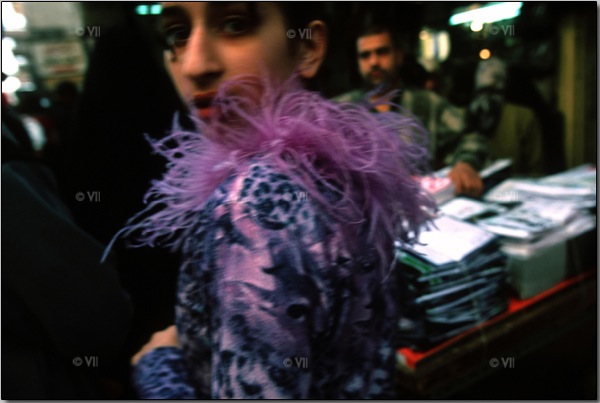

photo: Alexandra Boulat

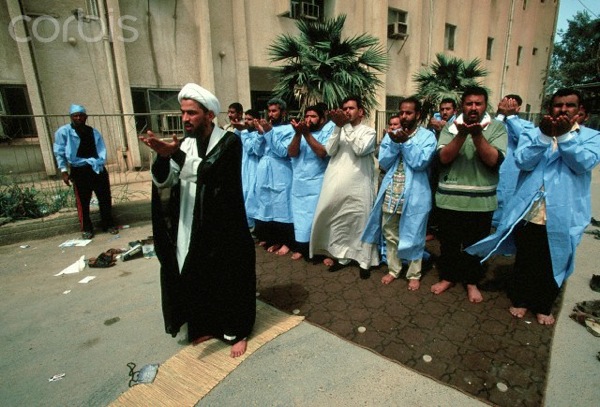

photo: Alexandra Boulat

A photograph that speaks for itself is a powerful thing. That’s the feeling I get from Alexandra Boulat’s series of photographs taken in continuous stream before, during, and after the U.S. began bombing the Iraq ten years ago yesterday. Not that photos can’t be powerful with narrative, including contextual afterthought to convey meaning or stylistic devices within the photograph, but for the most arresting sense of “the before,” there is nothing like what is happening right in front of the lens.

photo: Alexandra Boulat

photo: Alexandra Boulat

Boulat arrived in Iraq in February 2003 while it was under threat of attack from the United States. Her photos of pre-bombing Iraq show women without headscarves, western pop posters hanging in shops, people relaxing in cafes. It looks like a whole society. Not a perfect one (Boulat also shows scowling soldiers, suspicious looking government officials, and mental patients), but a whole one. One, as she says in her National Geographic narrative, people in the West can relate to.

photo: Alexandra Boulat

The photography moves to the photographs of the infamous Shock and Awe and invasion and the horrific, culture-splitting devastation wrought by U.S. action. Boulat captures the Baghdad skyline under attack, the city in rubble, and gangs of people scrambling to loot or to simply find supplies. Her subjects are dark and cramped and mourning. The photographs themselves, in their linear chronology, supply the context and the narrative. And certainly, ten years after America’s most hated war, we can supply context of our own. But how do you make sure this doesn’t happen again when the major players in deceiving the public are still spinning their justifications for that war and when the media aids and abets a war-like culture?

photo: Maya Alleruzzo

I’m thinking specifically of AP photographer Maya Alleruzzo’s stylish photos of post-invasion Iraq within a new photo of the same locale today. Photographs from Alleruzzo’s series are popping up in various galleries marking the tenth anniversary of the War.

The pic-in-pic technique was recently used by Hebe Robinson as she documented the history of a once-occupied, now deserted northern rural area in Norway. Alleruzzo uses the technique to show what, exactly? How the GI is no longer etched in the landscape? How much better things are now than when we occupied the country?

I think Robinson was more successful with the technique because nothing, other than nature, happened in the Norwegian interim: many of the buildings are still there, left to rot and return to earth. The photographic story is one of remoteness and abandon. In the case of Iraq, the rubbled city scenes, the park without orphaned children, the statue pedestal holding up nothing all mean something. They are evidence of what we did to a sovereign nation under false pretenses. What thousands of Iraqis and Americans died for. Perhaps it would have been more meaningful to me if Alleruzzo used Boulat’s photos of pre-invasion Iraq to make her point. Whole vs. destroyed and unmended. But without the real context, the pic within a pic technique comes up short, as if capitalizing more on style.

photo: Alexandra Boulat

Unfortunately, Boulat died in 2007. We don’t know what her reaction would be to the compare-and-contrast of Baghdad now and Baghdad as we broke it. You have to wonder (as the little boy checks his watch four days before the start of hostilities) if she wouldn’t steer the viewer to an earlier point in the Iraq timeline. — Karen Hull Donley

(Photos 1-5 & 8: Alexandra Boulat. Caption 1: Baghdad before the bombs. A young girl in a Baghdad street, during Saddam Hussein’s regime. February 2003. Caption 2: Loyalists to the regime of Saddam Hussein have lunch in a restaurant in downtown Baghdad, March 1, 2003, a few weeks before the U.S.-led coalition invasion of Iraq. Caption 3: Shiite doctors pray outside the Al Kindi hospital after the U.S.-led coalition invasion of Baghdad in April 2003. Caption 4: US Marines in Baghdad as the town is being ransacked by looters. Caption 5: Smoke fills the air over Baghdad in this April 2003 photo. During the three weeks of coalition air raids over Baghdad, Iraqis burned oil fires in and around the city, in a desperate attempt to blind jet fighters and fool guided missiles. Photo 6: Maya Alleruzzo. Caption 6: A March 14, 2013, photo of the crossed swords monument was shot at the same location as an Associated Press photograph taken by Karim Kadim of U.S. soldiers on Nov. 16, 2008. The crossed-sword archways that Saddam Hussein commissioned during Iraq’s nearly eight-year war with Iran stand defiantly on a little-used parade ground inside the Green Zone, the fortified district that houses the sprawling U.S. Embassy and several government offices. Iraqi officials began tearing down the archways in 2007 but quickly halted those plans and set about restoring the monument two years ago. Photo 7: Hebe Robinson. Caption 7: Edle, Anne and Fredrik were the last generation growing up in Hermannsdalen. From November until April the family lived completely isolated. When Edle was eight years old, her grandfather took her and her sister Anne to the top of the mountain. From there, they could look down on their neighbours in the village Vinstad. She had never seen other houses before. Caption 8: Armed with toy Kalashnikovs, a group of Baghdad schoolboys wait beside the Tigris River in Baghdad to greet a busload of foreign peace activists March 16, 2003. The activists came to Iraq to act as human shields in anticipation of the U.S.-led coalition invasion of Iraq. Like actors in a play, the boys sang songs praising Saddam Hussein in a little parade.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus