Notes

When Reality Isn’t Dramatic Enough: Misrepresentation in a World Press and Picture of the Year Winning Photo

This post was written by BagNews Publisher Michael Shaw with RIT Photojournalism professor Loret Steinberg and RIT photojournalism alumnus Shane Keller. (Full disclosure: Steinberg is a consultant to this site.) Keller was the subject of a photo which was part of a series entitled “The Crescent” by Magnum photographer Paolo Pellegrin. The series was recently awarded second prize in the Stories category of the 2013 World Press Photo contest and a second place award in the Issue Reporting Picture Story category of the 2013 Picture of the Year International competition, with the individual photo earning Photographer of the Year — First Place in the Freelance/Agency category of the Picture of the Year awards — one of 50 images submitted for that category.

******

What happens when a World Press Photo and Picture of the Year International award-winning photograph doesn’t show what it purports to show? Not through a mistake of interpretation or subjective opinion, but when the facts show the photo wasn’t taken where it was claimed to be taken and when the subject of the photo isn’t who the photographer says he is. What happens when a city is represented through photographs bearing photographer-written descriptions almost wholly plagiarized from a 10 year old New York Times article? Does it make it worse when the photos and the series in question, “The Crescent, Rochester USA 2012”, have won multiple awards and the photographer is Magnum’s Paolo Pellegrin?

First, a bit of background. Last April, eleven Magnum agency photographers set up camp in Rochester to archive an American city. It was the outgrowth of a project by a smaller group the previous year that documented a road trip in the western United States.

Choosing Rochester for the project was a romantic yet ironic notion. As Alec Soth writes in a project update on The New Yorker’s Photo Booth blog:

Initially we thought about Detroit, but it has already been so well covered by photographers. So we began thinking about other areas and Rochester came up. Given the demise of Kodak, the idea of a photographic archive in this place where so much photographic history was born made a lot of sense.

The photojournalism program at Rochester Institute of Technology was also an integral part of the project. RIT space and resources were made available to the photographers; RIT students were used as production assistants.

I can’t say the month long project, as an agency-wide effort or a true archive, has achieved much note — with one exception. Paolo Pellegrin has earned a good deal of attention with his photo-essay centered around drugs, drug violence and decrepitude in an area of Rochester known as “The Crescent.” Pellegrin’s stark black-and-white photos dramatically portrayed cops on the beat, fleeing gang members, funerals for gunshot victims, arrests, crime scenes, fatherless families, and, notably, a young, white denizen of The Crescent solely identified as a former Marine Corps sniper.

RIT professor Jim Johnson commented on the photos on his blog, (Notes On) Politics, Theory & Photography, on January 12, 2013 in a post entitled: “Parachuting In To Rochester.” Johnson’s post was “inspired” by the initial appearance of Paolo Pellegin’s Rochester photo story in the German publication die Zeit.

“I have to say that while the photography, unsurprisingly, is striking in many ways, the overall story Pellegrin presents is rather shallow and moralistic. We get a cat and mouse interaction between drug dealing ghetto youth (mostly racial/ethnic minorities) and officers (mostly white residents of the suburbs) from the Rochester PD. That “game,” I suppose, is meant to stand in for the racial and economic segregation that characterizes the Rochester metro area. … In short, we get a narrow glimpse of how things are, but nearly no understanding of how things got this way or, god forbid, any insight into what might be done to remedy the current, dire situation. It makes me wonder what photojournalists do to prepare for assignments and what they think their work is for.”

Reading Johnson’s post now, it’s interesting –perhaps fateful—that one photograph, present in the World Press Award and Picture of the Year International galleries, wasn’t published in the die Ziet article. The omitted photo was that of Shane Keller, identified by Pellegrin as a former Marine sniper described as being located in “The Crescent.”

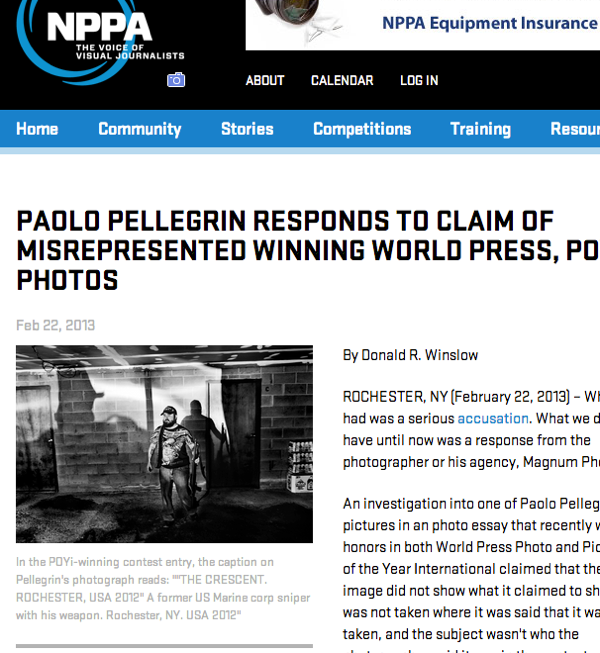

Shane Keller is a former marine but is not, and never has been a Marine Corps sniper. He does not, and never has lived in The Crescent section of Rochester. In fact, on the night the photo was taken, Keller was a student at RIT who, at the request of Pellegrin and a fellow student, posed for photos with his gun collection at his home close to Rochester’s Jewish Community Center. The photo was taken in Keller’s garage. Keller’s concerns about the intentional misrepresentation, the content of Pellegrin’s caption, and plagiarism in the series’ extended description were communicated in an email message.

A colleague recently informed me I’m in a photograph on World Press Photo by Paolo Pellegrin. He photographed me when the Magnum photographers were in Rochester last year. Brett, a classmate and one of the student assistants to Magnum, was driving him around, looking for stories, and he wanted to photograph someone with firearms or at a shooting range. That’s where my name came up. I owned a number of firearms and had a membership to the Genesee Conservation League (shooting range). Brett called me and said Paolo wanted to photograph portraits of us, which I was fine with. He then wanted to photograph us at a shooting range, which I agreed to, but ethically I thought it was strange that he would ask us to do something for him.

Paolo had first photographed me in my apartment with a plain white wall. He made some photographs of just Brett holding one of my pistols, which he can’t legally own in NY since he doesn’t have a NY pistol permit. Technically, he wasn’t even legally allowed to hold mine. After we were both photographed in my apartment, we went to my garage to leave for the shooting range. That’s when Paolo wanted to shoot a few more portraits of us down there. I’m assuming it was because it looked scarier down there and would go better with his story of “abandoned houses prone to become centers of drug sales and use.” As I recall, the photograph used was from when I came downstairs with my shotgun, as requested, but I think it was before he started shooting the portraits of me.

The caption bothers me even more than the photo itself, which says, “A former US Marine corps sniper with his weapon.” First, I was never a sniper and I never would have said that.

For any Marine who knows me and sees that image, are they going to believe the photographer and assume that I lied about my Military Occupational Specialty. That makes me look really bad and hurts my integrity. Second, the one line caption makes it sound like the weapon I’m holding is my sniper rifle, which it’s not. It isn’t even a rifle; It’s only a pump-action 12 gauge. And as a minor detail, the word “Corps” should have been capitalized.

Shane goes on and talks about the location of the photo:

The background [description for] all of the photos [identifies the locale as] the Rochester Crescent. I’m not sure what parts of Rochester are considered the Crescent, but I’m sure I wasn’t part of that region. I lived in a very safe neighborhood next to the Jewish Community Center along the border of Brighton and Henrietta. I probably could even have left my doors unlocked without fear of someone breaking in while I was gone.

In general, I don’t feel the portrait of me belongs in this story at all. As I already mentioned, I didn’t live in the Rochester Crescent. I wasn’t part of the city’s homicides, violence, drug sales and use, or lagging economy as the story says. I’m not sure if the purpose of this image is to make me look like I’m a danger to other people or to make me look paranoid from living in a dangerous area, which I didn’t.

Finally, Shane talks about the fact he is not identified:

Why wouldn’t Paolo use my name? I remember asking him if he needed my full name or anything else for his caption information and he said no. Even for us as students, we were always required to have names. Why would a Magnum photographer, of all photojournalists, not want caption information when it is being offered to him? I understand sometimes you can’t always get caption information, but that’s a lot different from just blatantly not wanting it. I honestly don’t understand it.

Shane also addressed how Pellegrin appropriated copy for his photographer statement and extended caption of the project.

I would think all photojournalists understand plagiarism: HERE you can read an article by Michelle York for The New York Times, published in 2003.

Two of the sentences in Paolo’s caption are exact, word for word copies from this article. A third sentence in his caption is essentially identical to the article, only taking out the name of the person being quoted. I did not see any citations for Pellegrin using York’s article.

Of course, the information provided for the description of the photographs can’t be accurate coming from a ten year old article. (In the footnote below, we compare Pellegrin’s submitted captions with the language of the NYT article.)

As one of Keller’s professors in the photojournalism program, Loret Steinberg had a chance to discuss this experience in the lull before anyone, including the larger photography community and the prize organizations themselves, absorbed this accounting. As Steinberg wrote to Keller, who was a student in her Ethics and Photojournalism class:

“Some of these issues of representation (image prep for dark and moody, seeing things in front of the camera in the same way no matter what the subject, etc.) are part of an ongoing ethics discussion. I’m sure you recall Patrick Schneider’s NC POY awards being taken from him — I used that example in ethics to introduce the ways that people expect photographs to represent what the reasonable viewer in our democracy would have seen had he/she been there.

Pellegrin’s photograph of you is only one aspect of a larger issue of authenticity, definitely makes anyone question other things he’s done and how he’s photographed people to show something he wants to show. Other photographers who leapt beyond the line forced us to re-examine their work more carefully (Bo Christensen, Schneider, Allen Deitrich, Edgar Martins, Brian Walski, et al). Yes, his work is powerful but he’s presenting it as photojournalism and documentary. That comes with a huge responsibility and expectation.

It is sad, really, that Pellegrin chose to do these things. Even without your photograph and its misrepresentation, there are people in Rochester (including me) who question his heavy-handed depiction of the real problems and issues that exist in the city. Our profession isn’t just about making pretty pictures that win awards but about making powerful photographs that may win awards because they reveal something authentic.”

The misidentification and plagiarism associated with Pellegrin’s photo series is a terrible thing to have to write about. At a time of turbulence in the world and a weakened press, the importance of the photojournalist — in the eyes of citizens, the media, the all-too-trusting award programs and particularly, in the admiring gaze of those who aspire to report with a camera — cannot be overstated.

Still, the need for integrity and authenticity cannot be overstated either.

UPDATE 1: Jim Johnson teaches at U. of Rochester, not RIT. Our apologies.

UPDATE 2: We welcome Paolo Pellegrin’s response to the post. Our immediate reply here.

UPDATE 3: Our response to the World Press Photo Pellegrin review and our role five days later.

—————–

FOOTNOTE: Below are the Pellegrin submitted captions for WPP, POYi, and Sony World Photography Award. They are mostly the same. In each caption/description, the numbers refer to exactly or nearly exact text in the December 24, 2003 New York Times article about The Crescent.

Pellegrin’s description published with the series as it appeared in the 2013 WPP Award gallery:

The area of Rochester, New York, USA, where these pictures were taken is part of the so-called ‘Crescent’, a moon-shaped area that runs across several city neighborhoods. Crime rates here are significantly higher than the rest of Rochester. 1. The Crescent is home to 27 percent of the city’s residents and 80 percent of the city’s homicides. 2. The causes of the burst of violence include the lagging upstate economy, a steady migration of residents to the suburbs, and a growing number of abandoned houses prone to become centers of drug sales and use. Rochester also has a school system that performs poorly. 3. People inside the Crescent experience those problems in greater concentration.

Pellegrin’s description published with the series as it appeared in the 2013 POYI gallery:

The area of Rochester where these pictures have been taken is part of the so called ‘Crescent’, a moon shaped area that runs across several Rochester neighborhoods and where crime rates are significantly higher than the rest of the city.1. The Crescent is home to 27 percent of the city’s residents and 80 percent of the city’s homicides.2. The reasons behind the burst of violence include the lagging upstate economy, a steady migration of residents to the suburbs and a growing number of abandoned houses prone to become centers of drug sales and use. Rochester also has a school system that performs poorly. 3. People inside the Crescent experience those problems in greater concentration. ” 4. It’s an area of great poverty and high consumption rate of drugs which fuels an incredibly high number of homicides,” said the Rochester police chief.

Pellegrin’s description published with the series as it appeared in the 2013 Sony World Photography Award write-up (for different photo in series):

“A man is arrested by the Rochester police after having assaulted his father with a samurai sword” by Paolo Pellegrin, Italy, 2013 Sony World Photography Award (Finalist for Current Affairs)

Photographer’s description: A man is arrested by the Rochester, N.Y., police after having assaulted his father with a samurai sword. 1. The Crescent is home to 27 percent of the city’s residents and 80 percent of the city’s homicides. 2. The reasons behind the burst of violence include the lagging upstate economy, a steady migration of residents to the suburbs and a growing number of abandoned houses prone to become centers of drug sales and use. Rochester also has a school system that performs poorly. 3. People inside the Crescent experience those problems in greater concentration. ” 4. It’s an area of great poverty and high consumption rate of drugs which fuels an incredibly high number of homicides,” said the Rochester police chief.

Paragraph in question from The New York Times December 24, 2003 article, “Mean Streets of New York? Increasingly, They’re Found in Rochester.”

1. The crescent is home to 27 percent of the city’s residents and 80 percent of the city’s homicides. 2. The reasons behind the burst of violence, according to Professor Klofas, include the lagging upstate economy, a steady migration of residents to the suburbs and a growing number of abandoned houses prone to become centers of drug sales and use. Rochester also has a school system that performs poorly. 3. People inside the crescent experience those problems in greater concentration. 4. ”It’s an area of great poverty and high consumption rate of drugs which fuels an incredibly high number of homicides,” said the Rochester police chief, Robert J. Duffy.”

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus