Notes

Photo: Erin Schaff/The New York Times Caption: Sunday worship at Old Fashion Gospel House, Bulls Gap, Tenn.

Picturing Vaccination Reluctance Among Conservative Christians

Vaccination reluctance—at least in small Appalachian towns—is not simply a matter of social irresponsibility or political allegiance. Instead, it involves a more complex conflict with faith.

by Philip Perdue

At small Baptist churches like the one pictured here, worship services close with an altar call where attendees are invited to kneel and pray publicly at the front of the sanctuary.

In this photo by Erin Schaff, one among several photos featured in a recent New York Times story about vaccine hesitancy in small religious communities, the two men have a private conversation with God in full view of other congregants. The whole ceremony is a sacred ritual for individual cleansing and reinforcing communal bonds among church members.

Photos of this ritual are not widely seen. But when viewed against the slow crawl out of a long public health crisis, where getting people vaccinated has turned into a problem of public persuasion, this photo offers up a religious play on herd immunity. For conservative Christians, the main impediment is personal devotion. While the stress on me and Jesus may promote symbolic conformity to group behavior, it also creates a rift with the wider culture.

Extend that conformity across rural Appalachia, and vaccine skepticism– along with social conservatism and an overwhelming preference for the Republican Party–has become a distinguishing feature of the population.

Caption: The Ballad Health community vaccine center in Elizabethton. Immunization clinics in the county have been desolate recently.

In Schaff’s photo of a free vaccine center, each empty seat shows how the practice of distancing is socially contingent and subject to regional variation. And with those black partitions mimicking the setup on election day, in a town of more than 13,000, given a choice between inoculation and recreation, many people appear to be voting with their feet.

Taken together with the story, Schaff’s images challenge the notion that vaccination reluctance—at least in small Appalachian towns—is a matter of social irresponsibility or political fealty. That dismissal is too quick, too easy, because it obstructs how people are trying to reconcile their stance on the vaccine with their conservative Christian dispositions.

With that religious element in view, Schaff’s images underscore the way vaccine availability is scrambling the usual sense-making narratives among people of faith in the region.

Caption: Rev. Guy Richardson leads Sunday worship at Old Fashion Gospel House in Bulls Gap, Tenn. In communities like these — mostly white, evangelical Christian and Republican — resistance to the Covid vaccine is difficult to combat.

In their aesthetic style and range, Schaff’s photos offer a window on the social independence and institutional distrust that is fostered in so many small Christian churches across the hills and valleys of Appalachia. This photo of a small church gathering once again returns to the visual trope of empty pews, perhaps in another nod to social disinterest. And yet, it’s an even better illustration of the bottom line. Jesus Christ may be the overarching symbolic fixture, but what it captures above all are “the vaccine uncertain” turning to the people they trust.

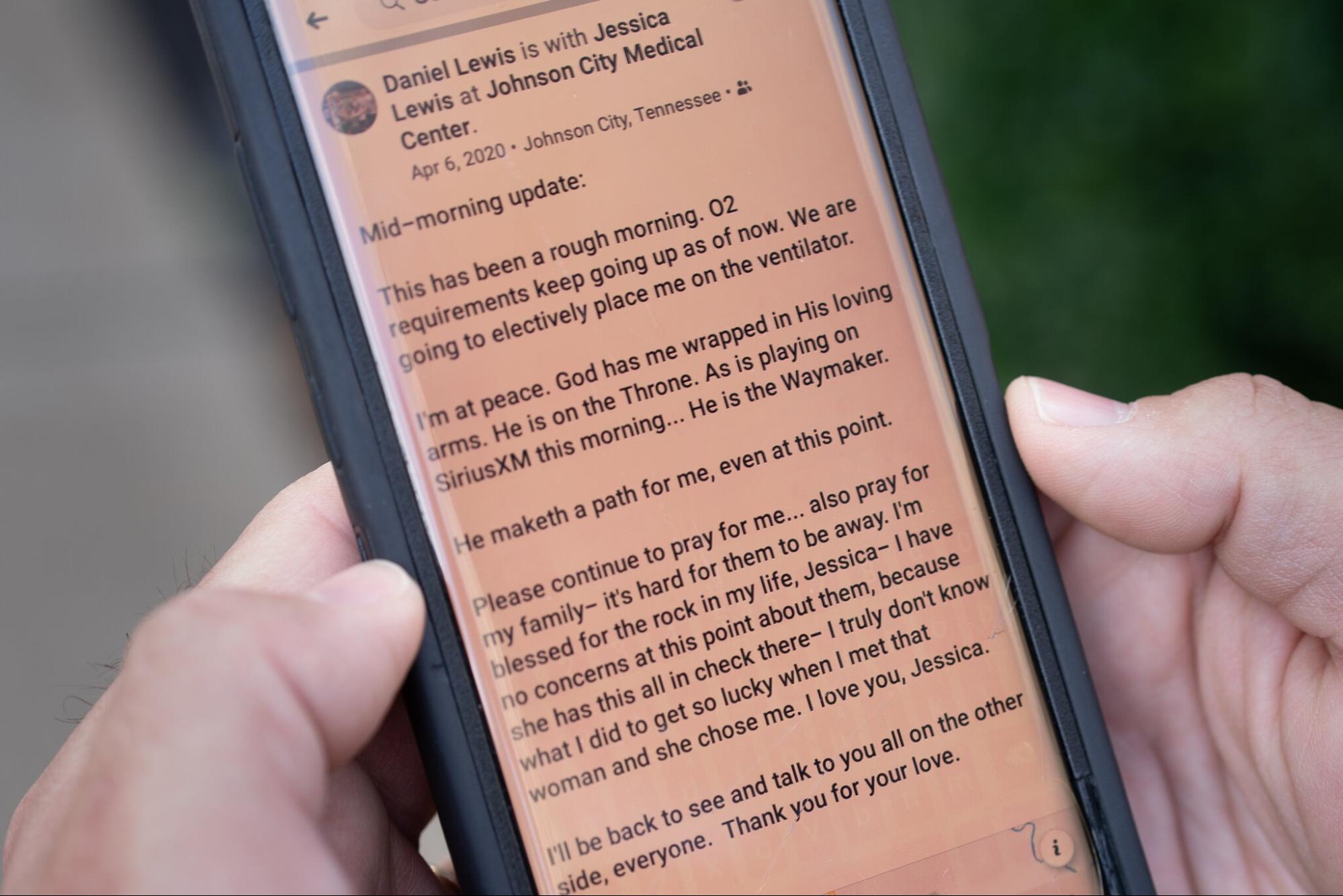

Caption: Dr. Lewis posted a dire hospital update. The community showered his family with support, including a prayer chain.

In that context, this photo of an email from Daniel Lewis, a physician in Greeneville, Tennessee who nearly died from Covid, shows one way to handle a characteristic limitation of news photography, which is how to depict the verbal or linguistic basis of social bonding. People such as Lewis who belong to a conservative Christian milieu cultivate interpersonal trust through sharing an idiom of God-talk, or Bible-talk, and by describing personal experiences such as illness as part of a divine plan.

Caption: The people of Greene County are emphatically Republican and overwhelmingly Christian.

Lewis’s email about God being on the throne, and his reference to reconnecting with family in the afterlife, on the other side, are both consistent with the injunction to “prepare to meet thy God.” Both envision a grand cosmic order in which human foibles on Earth are subject to the designs of an all-powerful deity.

Understandably it is hard for secular audiences to relate, but the crucial piece here when it comes to vaccine hesitancy is that sometimes it’s hard for people of faith to know if a decision they make is or is not running crosswise to a divine plan. Public health policy hardly registers when identity is based on trusting God to be in control in matters of life and death.

When head and heart are conflicted, when there is a dispute between one’s obligation to the divine order and one’s better senses, that experience can be deeply painful for people who want to do the right thing but can’t know for sure what it is.

Caption: Mary Hayes struggles over whether to vociferously defend the Covid vaccine.

This photo encapsulates the distress of community fracture around the vaccine. The image intimately captures the trauma shaping the post-pandemic transition among some people of faith. Mary Hayes’s eyes reflect the pain of a person who is having her religious faith tested. Religion is supposed to provide stability, but when it issues loyalty tests in situations that don’t make sense, it causes suffering.

In the face of frustration over vaccine hesitancy, people in small, tightly connected faith communities are unsure who they can openly talk to or who they can trust. If there is any consolation, it can be found in empathy for that struggle and the shared appreciation that this is not just a social adjustment but an existential one.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus