Notes

Here Are the Photos of People Suffering and Dying of Covid

Notice: This story contains photographs of bodies in conditions of severe illness and death. They may be troubling and difficult to look at.

Nearly 350,000 people have died from coronavirus-related illnesses. The scale of that loss for many of us defies comprehension. As the number of dead continues to rise, photojournalists have to carry the burden of representing the staggering facts and the detail. But some people are questioning whether photographic coverage of the pandemic is up to the task or not.

Specifically, academics and journalists have criticized the lack of photos showing people suffering or dying from the virus, claiming that such images do not exist.

On May 1st in The New York Times, historian and visual scholar Sarah Lewis penned an op-ed leading with the title: Where Are the Photos of People Dying of Covid? Acknowledging that “there have been some professional images from inside medical zones,” she otherwise insists that such photos “remain rare.” Just recently in a podcast on WNYC’s The Takeaway, Lewis reiterated her point, saying that “we don’t have images of what is very hard to depict, the human cost and the suffering that is happening.” She continued: “What we’re not seeing—and it’s difficult to even visualize—are those who have died of Covid, who are dying of Covid.”

Again on May 12th, in a column for Al Jazeera, journalist Patrick Gathara raised a similar complaint. He contends that western media outlets are telling “the story of the coronavirus deaths…largely through infographs and statistics rather than images. Unlike the victims of Ebola, the tragedies of coronavirus victims are demonstrated in numbers, not photographs.”

And in a New York Magazine article published on May 15th, Andrew Sullivan notes “a strange similarity between the casualties of a plague and those of a war in modern America: we never see the bodies. I have yet to see a Covid19 patient in the terminal phase of the illness….There are no photos of the dying; and very few that even show the toll of survival.”

I found these comments not just surprising, but stunning. In the sixteen years I have followed news photography, I never would have imagined that pictures depicting the ill, the dying, and the dead would reach the volume and visibility we have seen in this crisis so far.

It was a photo of a dead body on the street in Wuhan, in fact, that first caught my attention and made me think that the coronavirus could turn into a significant crisis. The photo, made on January 30, 2020, clearly shows a man lying dead on the street, while two men in hazmat suits stand by.

Caption: Emergency staff in protective suits check the body of a man who collapsed and died in the street in Wuhan on Thursday.

This photo was distributed right away by international news agencies and has been publicly available since the beginning of February. Since then, we at Reading the Pictures have collected several hundred of the most distinctive news images of people suffering or dying from Covid. At our website alone, we already have an archive of 35 posts dedicated to news photos of the crisis. Our analysis of these photos dates back to February, and it includes four editions of our biweekly Chatting the Pictures webcast where we discuss current news photos in depth.

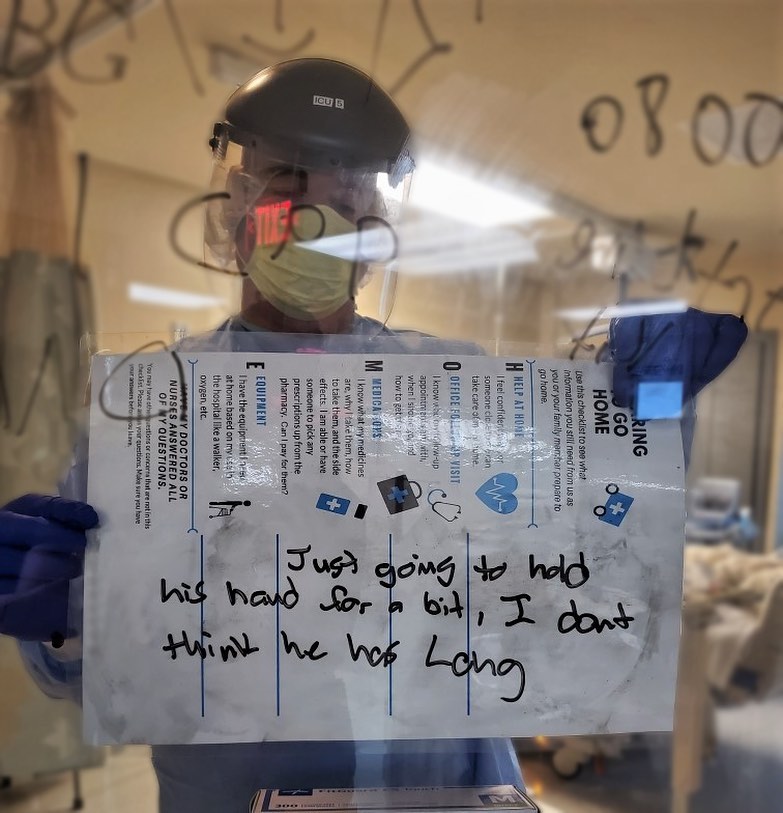

Our purpose for assembling and publishing disturbing photographs of people who are suffering, mortally ill, or have died of the illness is inspired by more than just setting the record straight. In collecting just a few of the most vivid and challenging examples in one place, our intention is to highlight the intensity and the critical detail that has commanded their publication. These photos—also showcasing the compassion and tireless dedication of hospital workers—constitute the visual essence of this moment and the emotional bottom line to the notion that “we are in this together.”

Caption: An EMT wearing personal protective equipment prepares to unload COVID-19 transfer patients at the Montefiore Medical Center Wakefield Campus on April 6 in the Bronx borough of New York City.

We have purposely limited our selections to photographs made in the United States. We established this criteria because American media often are reluctant to publish graphic images of pain and suffering. But even with the traditional resistance to publishing so-called “graphic imagery,” including scenes of stricken Americans, the photographs we’ve assembled have overcome obstacles of permission, access, HIPAA confidentiality laws, and serious risk to the health and safety of medical professionals and photojournalists so that domestic stories of the pandemic are not hidden from view.

In fact, so many images of suffering have been published since the virus took hold in the United States, we should be careful to emphasize what we do not cover here. We do not focus on wrenching photos from funerals. We don’t focus on images of anguished medical workers risking their lives without adequate supplies or equipment. Nor do we address distressing scenes from nursing homes or powerful photographs of mass graves.

Caption: Two bodies on hospital gurneys wait to be stored in a mobile morgue, put in place due to lack of space at the hospital, outside of the Brooklyn Hospital Center in Brooklyn, New York, USA.

We’ve instead selected from photos that are the most sensitive, that bring us to the closest boundary between life and death. Those are the photos of Covid patients and emergency medical technicians, images from hospital ICUs, and photographs of the handling and processing of corpses. These photos touch our hearts, while at the same time allow us to see and understand the unusual and extreme medical measures required by the disease.

Caption: Nurses and doctors clear the area before defibrillating a patient with COVID-19 who went into cardiac arrest, April 20, 2020, at St. Joseph's Hospital in Yonkers, N.Y.

Each one of these photos confronts us with a sense of life-and-death urgency that is rare among newswire photographs. Unusually explicit, this photo of a black man in cardiac arrest condenses the conversation around race, the precariousness of our health care system, and the proportionality of Covid-related deaths among people of color in the U.S. The photo also exemplifies how photographers have strived for images that protect the patient’s face from being identified.

Other photographs, like the one below, are more deliberate about emphasizing individual faces:

Caption: A medical worker in New York City holds a photo of a peer who died from the coronavirus, during a protest on April 3, 2020.

While we did not find any images by news photographers documenting the moment of death inside a hospital, in this image we see a medical worker bearing witness to the death of a colleague likely due to the lack of protective equipment.

Caption: Sal Farenga washes the hand of a body in preparation for the embalming process.

In numerous interviews, medical professionals have emphasized the importance of touch, and have delivered that comfort to patients they’ve treated in the ICU in spite of all the protective layers. In this case, the photo of a mortuary worker washing the hand of a body in preparation for embalming offers the viewer a similar kind of intimacy.

Caption: Bodies are wrapped in protective plastic in a holding facility at the Daniel J. Schaefer Funeral Home on Thursday, April 2.

It is customary to cover bodies of the dead and transport them in bags. What has been far less customary however, and may be shifting in the pandemic’s wake, are corpses driving the visual story. The pandemic seems to be revising old taboos and editorial inclinations around respect for the departed. It may be too soon to say how families and communities, large and small, will be haunted by the ghosts of Covid. But what photos like these make immediately clear is that we all now stand in the shadow of death.

Caption: REACT EMS paramedics wearing protective load a potential coronavirus patient for transport in Shawnee, Oklahoma, April 2, 2020.

How is it that Sarah Lewis and others have either not seen this imagery, or have not appreciated its breadth?

One possibility is that it is still too early. The question might have limited value as people are reeling from the crisis while it still is unfolding. Another is that there is just less news photography being produced and disseminated today, and especially so at the local and regional level. Yet another factor is people’s uneven access to media. Many of these images have been commissioned by The New York Times, New York Magazine, and TIME, or by the top photo agencies such as Reuters and Getty, but their audiences are limited. CNN’s recent photo essay of a funeral director may have been seen by a wide audience, but unless you are following these publications or the newswire feeds as closely as we are, limited exposure remains a factor.

Caption: Wednesday, April 22, 2020 Paula Johnson, a registered nurse, administers a deep suction tube into the lungs of a COVID-19 positive patient, in the intensive care unit of Roseland Community Hospital on the South Side of Chicago.

Perhaps it is better to ask, then: Why are so many explicit and wrenching photos of suffering and death in America being published as a result of the coronavirus?

Many have compared Covid-19 to 9/11 as “mass casualty” events, both centered in New York, American media’s “Ground Zero,” and both events inflicting serious emotional and economic damage on the country. But only a few pictures of bodies were published from 9/11. Even the photo of the “Falling Man” was on the cover of The New York Times for only a few hours before being removed, apparently in response to reader complaints.

Caption: Nick Farenga retrieves the body of a Covid-19 patient from a refrigerated trailer outside a hospital. (A small area on one body bag was altered to obscure a name to protect the privacy of the deceased.)

And yet the most salient difference between viral outbreak and terrorism is that the pandemic is a worldwide public health crisis, not a social or political one. Of course, there are many aspects of the crisis which heighten existing social and political divisions. Aid relief has not been equitable. The poor and people of color have suffered much higher infection rates. And the president is doing his best to politicize it. But it is still a humanitarian crisis.

Caption: A COVID-19 patient receives support from a ventilator in a negative pressure room (NPR) at Gulf Coast Medical Center in Fort Myers, Florida. NPRs help prevent cross-contamination from room to room.

It’s also a threat that directly implicates individual bodies and exposes serious weaknesses in public health infrastructure. To that extent, we are indebted to the photographers and the photography. As Nina Berman, professor and director of the photography program at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, explained to us in an email, “Stay at home orders would not have been possible without the photojournalists doing this work. No one would have believed the virus was serious. Perhaps early on there was a time when grief and suffering were not so readily seen because of the risk of infection. But that has changed. Photojournalism quite literally saved lives.”

As excruciating as it is to examine these pictures, we believe there is an impetus to see them. Because the virus is invisible and vigilance is hard to maintain, these photos illustrate the power and the threat of the disease. They expose the consequences of taking the threat too lightly. More than that, they capture the mortal essence of the crisis and its practical and moral challenge to our humanity. –Michael Shaw

Caption: An EMT wearing personal protective equipment prepares to unload COVID-19 transfer patients at the Montefiore Medical Center Wakefield Campus on April 6 in the Bronx borough of New York City.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus