Notes

The Infected Primary

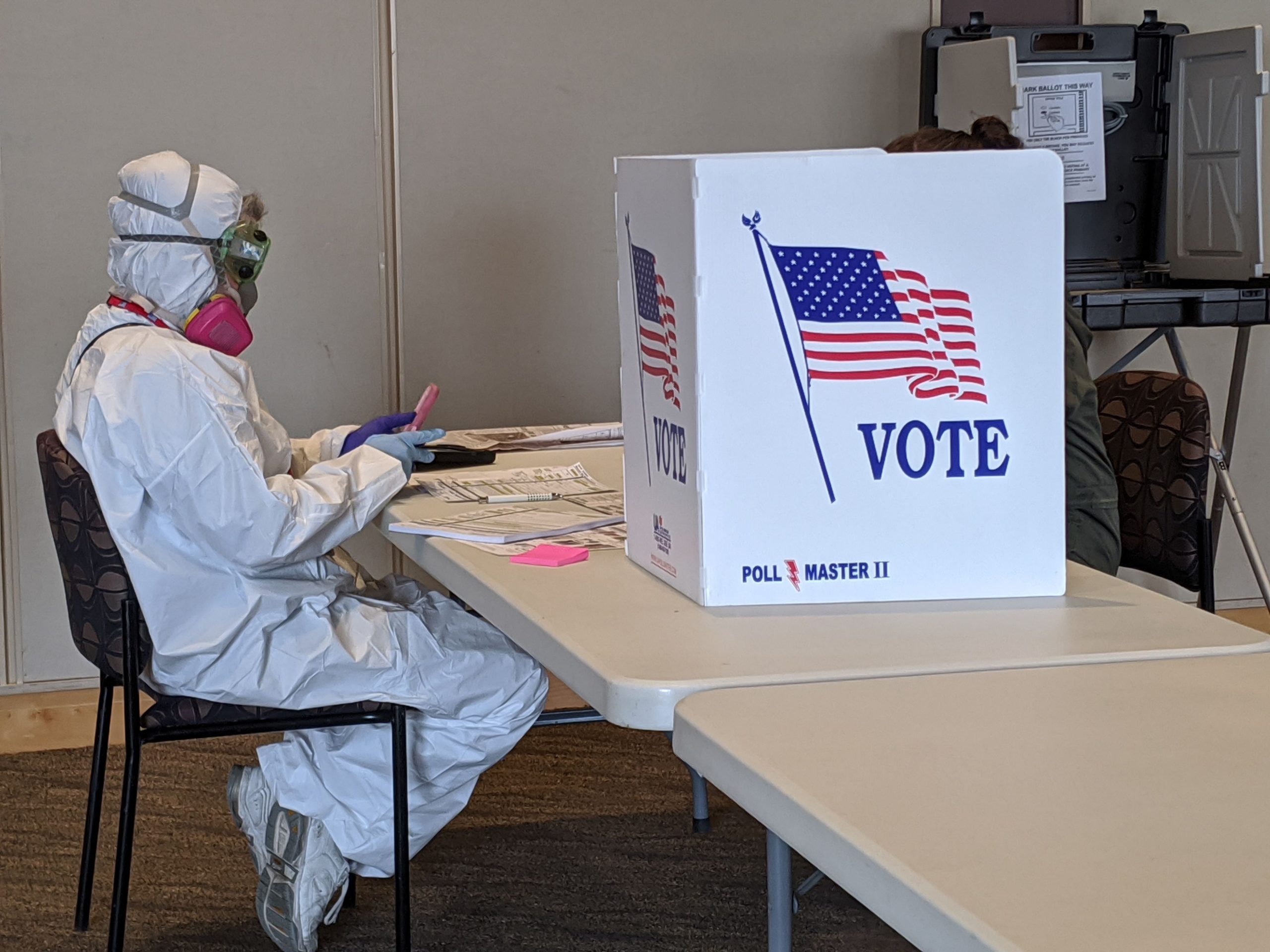

Photo: Derek R. Henkle/AFP via Getty Images Caption: Elections Chief Inspector Mary Magdalen Moser runs a polling location in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in full hazmat gear as the Wisconsin primary kicks off despite the coronavirus pandemic, on April 7.

It is hard to predict the future. Still, it’s easy to imagine that by the time 2020 ends up in the history textbooks, the novel coronavirus will be remembered as a point of leverage used by the right to alter the fabric of American democracy.

Last Tuesday’s primary election in Wisconsin made it abundantly clear, for example, that Republicans will put public health in harm’s way if it means another chance to sabotage the electoral process. Beyond suppressing the vote, what other reason is there to insist on public assembly during a statewide stay-at-home order?

And what is it but an outrage that Mary Magdalen Moser, Elections Chief Inspector for the city of Kenosha, Wisconsin, had to go full Tyvek suit and dual-cartridge respirator just to do her job on election day? You might point out that even our sense of caution is politicized these days, so say what you will about the level of protection here. But when participating in the democratic process poses a clear and present danger to public health, we all should be able to admit that signs of political malfunction are staring us in the face.

Viewed as an inflection point in democratic decline, this photograph of hazmat Mary may in the future have less to reveal about the way people are taking head-to-toe precautions against coronavirus. Instead, what has lasting potential in this photo is its almost casual recognition of how toxic voting has become in the United States.

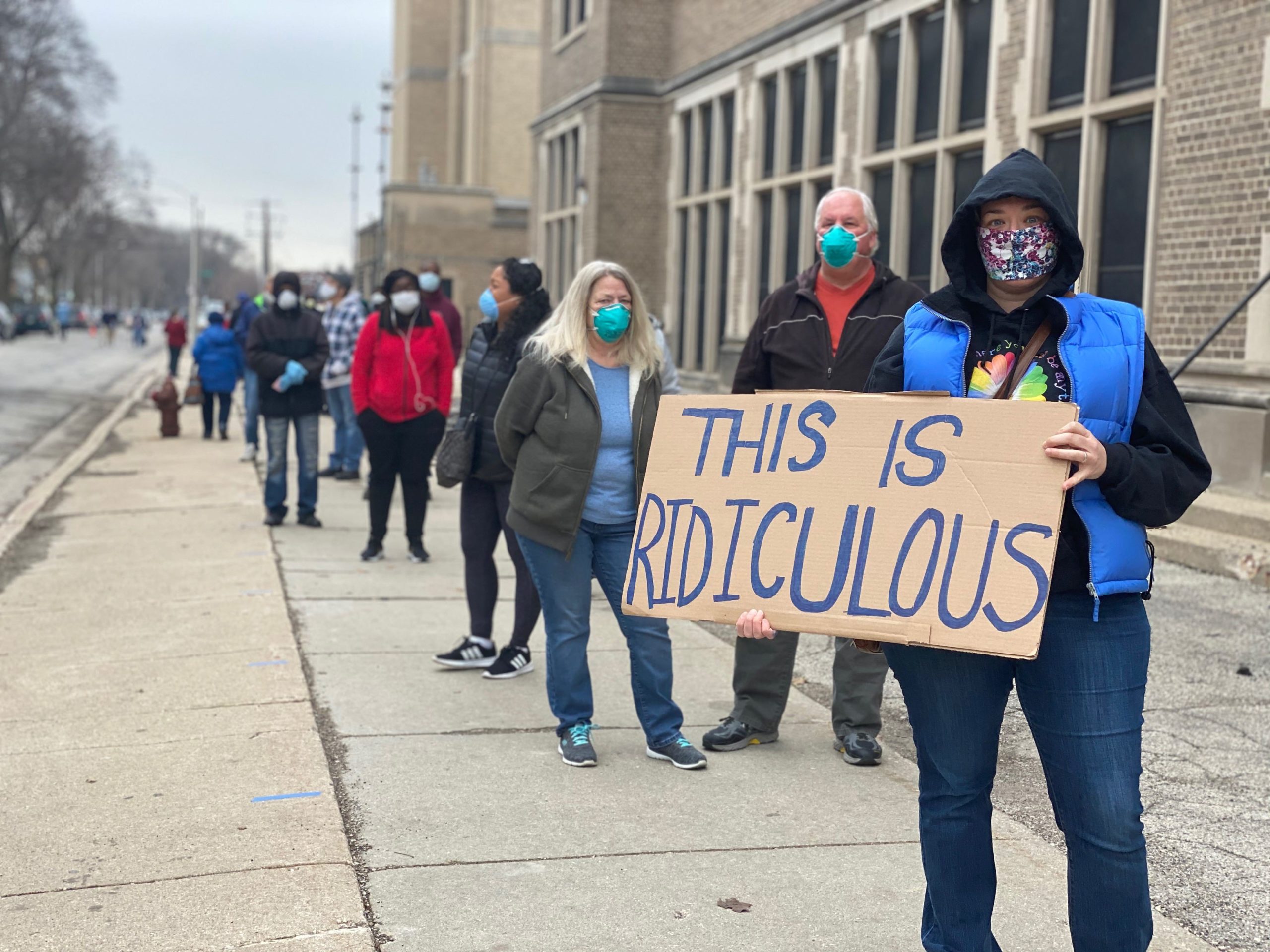

Photo: Patricia McKnight/Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Caption: Milwaukee resident Jennifer Taff holds a sign as she waits in line to vote at Washington High School in Milwaukee on Tuesday. “I’m disgusted. I requested an absentee ballot almost three weeks ago and never got it. I have a father dying from lung disease and I have to risk my life and his just to exercise my right to vote.” She said she had been in line for almost two hours.

In Wisconsin, the noxious political machinations behind Tuesday’s primary debacle were not lost on voters who violated their state’s stay-at-home order to cast their vote.

For Milwaukee resident Jennifer Taff, who requested but did not receive an absentee ballot, her cardboard sign frames how we’re seeing postures of resignation and endurance there on the sidewalk. Taff’s handmade sign, paired with the red white and blue mask, punctuates the absurdity of Milwaukee’s polling problem and the muzzling effect it has on voters.

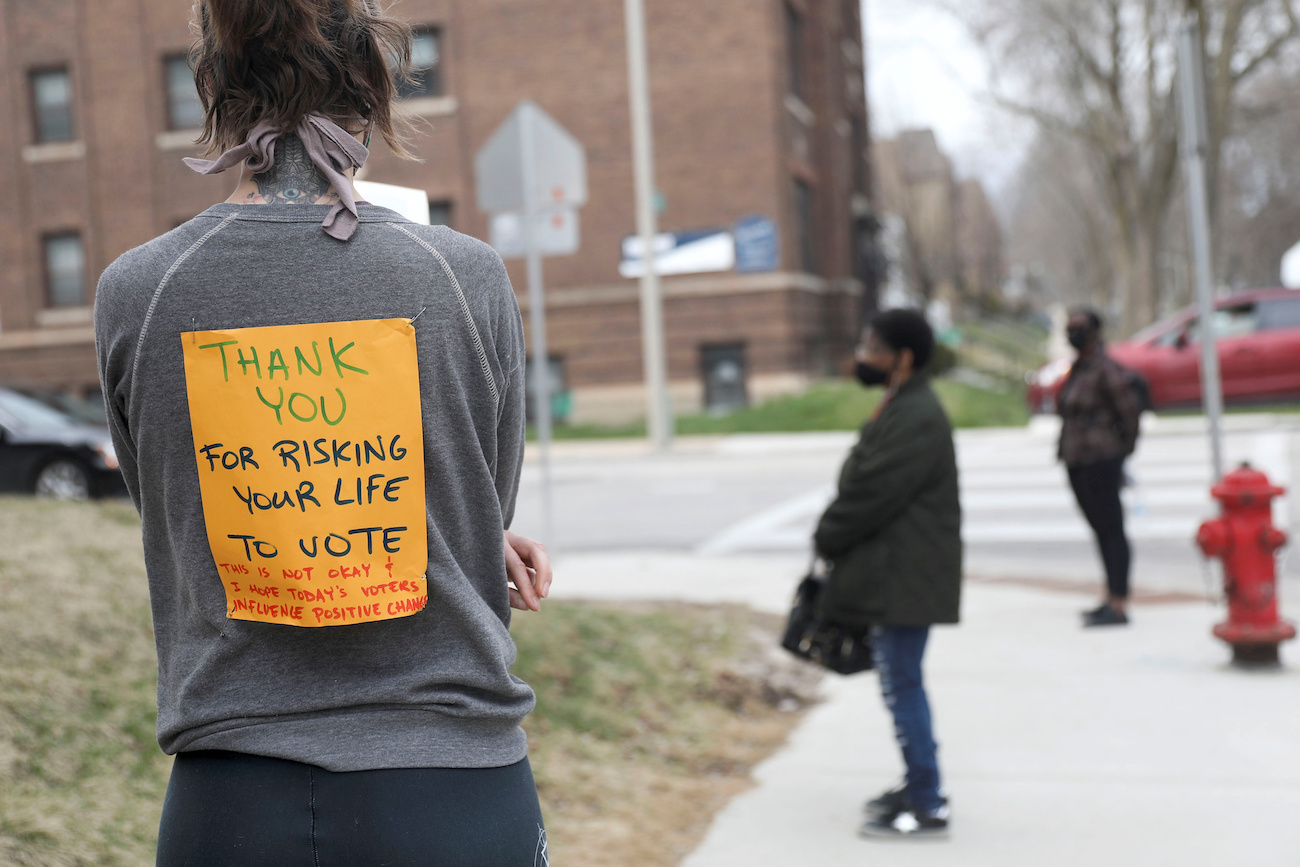

Photo: Daniel Acker/Reuters Caption: Voter Rachel Messenger wears a sign reading “Thank you for risking your life to vote” as she waits in line outside Riverside University High School to cast a ballot during the presidential primary election in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, April 7.

What we’re also seeing in photos of the Wisconsin primary is how anti-democratic forces in the U.S. typically stand at a crossroads with dissent. That is still true in 2020.

From this vantage, it is good to see the back of Milwaukee voter Rachel Messenger. Her protest signage is both a fitting response and a nod to strangers who, like her, are risking their lives to vote. “This is not okay,” the fine print reads, and “I hope today’s voters influence positive change.”

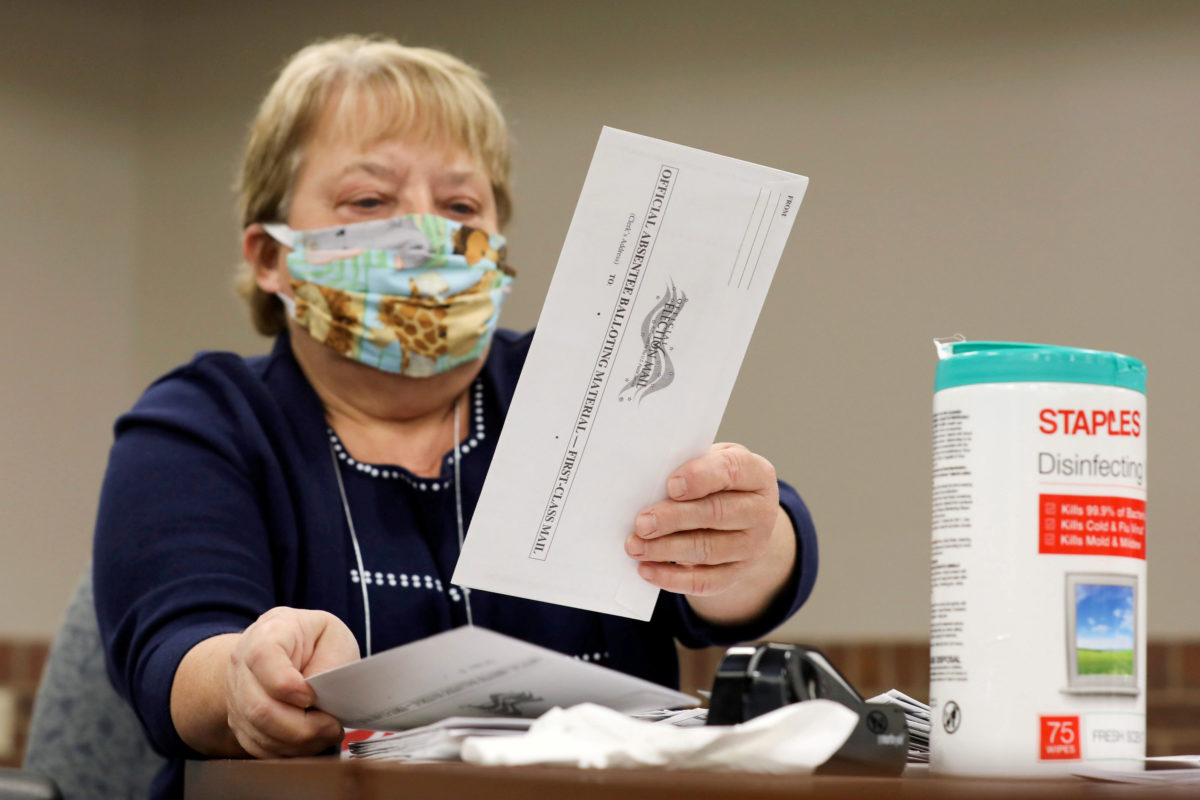

Photo: Daniel Acker/Reuters Caption: Election volunteer Nancy Gavney verifies voter and witness signatures on absentee ballots as they are counted at the City Hall in Beloit, Wisconsin, April 7.

Change. No election cycle makes sense without appealing to it. Life during and after coronavirus will exemplify it. Some of the changes we are aware of already while others we are seeing have not yet been named.

Take for example this photograph, which brings us back into a polling station in Beloit, Wisconsin, where a volunteer named Nancy Gavney processes a stack of absentee ballots. Going without gloves, she is fortunate to have the mask and disinfectant wipes that are now a staple of protection from coronavirus. Like all the other election workers and volunteers, Nancy is putting herself at risk by handling potentially contaminated materials. To them, we, too, say thank you for risking your life.

They are models of civic responsibility. More pointedly, voters who went to the polls in Wisconsin, and poll workers who exposed themselves to risk on behalf of the democratic process, are giving us a fresh look at what the contours and equipment of patriotism can look like.

–Philip Perdue

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus