Notes

The Black Hole Picture: Ultimately, the Viral Image is More a Reflection of Ourselves

If we really can’t see a black hole, the next best thing is a picture we find familiar.

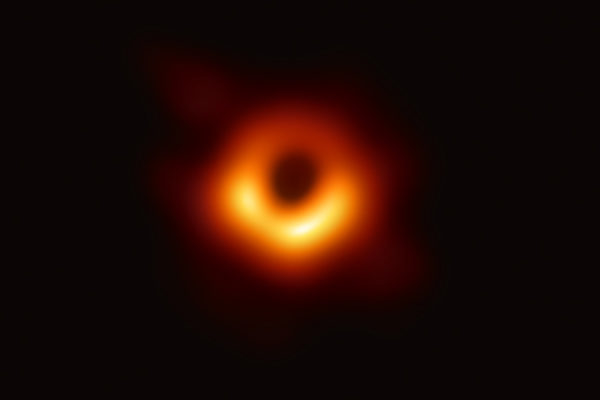

Photography requires light, and yet here is the first image of a black hole, something that swallows light. A black hole’s gravitational pull is so strong that photons—those massless particles that produce light—get dragged in and cannot escape.

This image of a black hole in the center of galaxy M87 was released to the public this week by the Event Horizon Telescope, a planet-scale array of eight ground-based radio telescopes forged through international collaboration. It isn’t quite a photograph, though, at least not in any conventional sense of the term. The Event Horizon Telescope produced reams of data, and the image we have is a computerized rendering of that information. Strikingly it looks much as it was thought it would, as Einstein predicted.

It took graduate student Katie Bouman of MIT three years to design the algorithm that reconstructed the image of the black hole. Bouman’s effort required so much data—five petabytes, in fact—that she needed a stack of special hard drives to crunch it all. As observed by the Computer Science & Artificial Intelligence Lab (CSAIL) at MIT, Bouman’s accomplishment visually replicated that of another woman coding pioneer, Margaret Hamilton, who wrote stacks of code that helped put a man on the moon. Dr Bouman is now an assistant professor of computing and mathematical sciences at the California Institute of Technology.

The algorithm Bouman produced not only had to interpret the data to give a “correct” vision of what a black hole would look like, but also had to be rendered visually in a way that would be legible both to specialists and general audiences. Algorithms, coupled with genuine human excitement, also made the first image of a black hole go viral.

Still, because it is the product of so much computer imaging and data crunching, there is a lingering sense that we have not yet photographed, and therefore not yet seen, a black hole. This sense ignores the full spectrum of photographic imagery that can be produced by exposure of some sort of energy—light, x-ray or others—to a receptive source, be it film or a digital sensor. Even the digital single-lens reflex camera (DSLR), now widely used by photojournalists, requires algorithms to interpret the data captured by a sensor. In this way the black hole image falls within the scope of modern photography: sensors capture data that is then rendered to pbroduce the image we see.

However, complete fidelity is still beyond our technological capabilities. Even with this new discovery, our space-sight is fuzzy, like a newborn’s. We remain as we always have been, trying to discern the universe beyond us. Because it is so hazy, the black hole image requires interpretation. It demands that the viewer derive understanding by relating it to personal experience. This is how people everywhere, even if they are not “into” science, can see something familiar in the image, whether it’s humanity (the eye), religion (the halo), or fantasy (the unknown). We remain as we always have been, then, trying to understand the new by relating it to the familiar.

Popular culture inevitably will shape what we see in the black hole image, and the description of the black hole as a “monster” will lead many to see just that. A ring of fire, the eye of Sauron perhaps, hunting us, ready to devour us. Doomsday theorists may read some portent into it. The devout may see a halo and look to it as a sign of a holy event on the horizon. For some Christians, the proximity of Easter and the black hole image release may hold extra significance.

Such interpretations must be brought to the image partly because the black hole is unknowable, massive and distant in a way that defies human logic. However, we can make some sense of the black hole by noting its familiar elements: the circle of brilliant, orange light and dark center, which as humans we recognize and are drawn to as if it were an eye. This ocular likeness may contribute to its power. We also are compelled to focus on it because all we have is an orange circle encompassed by negative, black space all around. Like when confronted with prolonged eye contact, we are captivated by this image and we fall, pulled by its gravity, into the dark “pupil” at the center. Are we, perhaps, hoping to see a reflection of ourselves?

Maybe this hope informs our continuous exploration as we search inexhaustibly for what is “out there” in the universe, looming for a grander meaning to life or our place in this great expanse. Who, or what, is watching us though?

Among all this unknown, still there is something definite that we can see. The brilliant, orange ring of light found at the event horizon, the very edge of the black hole, forms a circle around it as if to say “here it is!” It’s the equivalent of a neon truck-stop road sign buzzing in the night. This luminous halo, brighter than all the billions of other stars in the galaxy combined, is created by superheated gas falling into the hole. This is why it can be seen at such distance from Earth.

Scientists now are trying to produce an image of a black hole much closer to home—in the center of our own galaxy, the Milky Way. Our “local” black hole will be harder to reconstruct because its halo is not as bright. Maybe in this case we are too close to see clearly, since it is harder to seek answers closer to home, tougher to look inward than outward. Surely our species capacity for introspection does not guarantee self-awareness. So it is that we look outward for solutions and answers instead of tending to our own planet when there is much that needs to be done.

— Edward Brydon

Photo: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration, via National Science Foundation. Caption: The first image of a black hole, from the galaxy Messier 87. This black hole resides 55 million light years from Earth and has a mass 6.5 billion times that of the sun.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus