Notes

On the Border Family Separation Crisis: There are Enough Pictures Now

There is no photograph of a breastfeeding child being ripped from her mother’s breast.

There is no photograph of an inconsolable toddler pummeling her mat with tiny fists.

There is no photograph of the lasting harm done to children torn from their caregivers at the border.

There is, however, a powerful urge to see, a demand for pictures that is both catalyzed by the pictures we do have and premised on the idea that seeing pictures will spark action.

From Senator Merkley’s failed Facebook Live effort to enter Casa Padre to journalist Jacob Soboroff’s descriptive tweets and multiple TV news appearances to official photographs released by the Department of Health and Human Services and by the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol to John Moore’s now viral picture of a toddler wailing while Border Patrol agents detain her mother, pictures—and their lack—are circulating as proof of what is happening on the U.S.-Mexico border right now. But what sort of proof do they offer and what can we learn from them?

No matter their source, the photographs of detained migrant children are damning. Children lie on green mats in the middle of a chain-link cage. Some try to rest, others gather around a guard. The silver mylar ‘blankets’ thrown oversleeping kids may be effective at trapping warmth, but they cannot offer comfort. These are children in cages; no amount of bible quoting will justify it.

It is hard to look at photographs of detention centers and square them with a simple fact of provenance: these photographs were provided by the U.S. agency responsible for the creation and operation of the cages. These photographs are the most cosmetic images they can offer of the spaces where children are first imprisoned after they have crossed the border alone or been taken from their parents. Even so, these photographs don’t really offer an insurgent “right to look” that calls authority to account. Instead, they seem to provide a sort of official acquiescence (“okay, sure, you can look”) and a prelude to the chain of endless buck-passing that goes all the way up to the President of the United States. Pictures retain their powerful link to reality, and the reality shown is horrific, but, shrug, what can be done?

When I call one of my Senators to voice my outrage, that is—more or less—the answer I receive. The other offers a list of actions planned, from proposed legislation to possible financial strangle-holds. I wonder if the toddler is still crying. I wonder if that mother’s breasts are aching with milk for her baby.

I have read Susan Sontag carefully enough to be skeptical of any claim that seeing pictures of abuse will catalyze public action. And yet, that does appear to be what is happening right now. For nearly a month, my social media feed has been quietly bubbling with outrage at the policy of family separation, but it has boiled over in the last week as photographs have become available. Suddenly a wider circle of my acquaintances is sending money, calling representatives, and joining protests. Over the weekend, the New York Times editorial page offered pointers on how to make a difference.

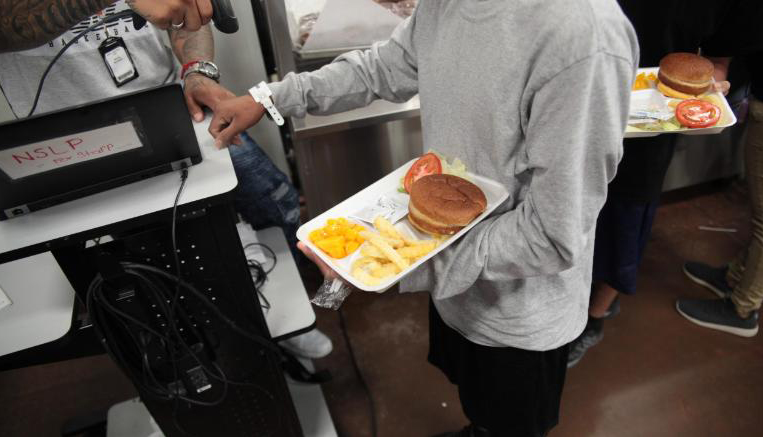

It’s the cages that are sparking outrage, but it’s also the quieter scenes, like this one of a boy holding a plastic tray of banal-looking cafeteria food. It looks innocuous until you see the tattooed attendant isn’t scanning items, he’s scanning the wristband strapped around the kid’s wrist.

Then the fact that no one has faces—they’re all cropped out of the photograph—becomes not simply a way to protect identities but a sharp reminder that this child’s identity has been stripped from him. He is a migrant. Detained. Deportable. And this boy is probably a teen. He may have come across the border unaccompanied. What about the kids too young to choose their own food or stand in a line or grab their towel from a rack and head to the showers?

The official photographs, as other commentators have pointed out, all show older boys. We know, though, that children of all sexes and ages have been separated from their parents. If showing older boys offers a—so far mostly ineffective—way to contain the outrage these photographs elicit, what difference would showing the little ones make?

Photojournalist John Moore seems to be trying to capture this moment at a child’s scale. The resulting photographs are simultaneously balm and fuel when viewed alongside the photographs provided by federal agencies. The human intimacy infusing them makes the institutional inhumanity of the agency-provided photographs even more palpable. It is no wonder that one of Moore’s images has gone viral in recent days (and was featured in last week’s “Chatting the Pictures”). These photographs gain new perspective and import when viewed alongside the photographs from inside Casa Padre and the U.S. Border Patrol’s McAllen, Texas facility.

While not all of Moore’s photographs are at child scale, some of the most powerful ones are. Adults are seen only from the waist down as the pictures become kid height—the visual equivalent of kneeling down to bring yourself into kid proportion. Though truncated, the adults in Moore’s photographs still loom large—parents and officers—and each angle offers a different way to recognize the children’s plight, caught up in the schemes and injustices of grownups.

These two pictures of a father and son strike me particularly in the different ways they frame what’s going on—one calling attention to the impossible burden placed on the little boy, the other allowing him a few last moments in his father’s protection.

News outlets have been choosing one photograph or the other to illustrate their stories of family separation, but I keep viewing them alongside one another and playing their chronology back and forth in my head. I imagine the little boy clinging to his father’s side, seeking the simple protection offered by a caregiver’s hand, and then having to step forward and—perhaps—go with the agents. Or maybe he stepped forward first, in a fit of small-child confidence, and then, realizing the enormity and threat, retreated to his father’s side.

Whatever their order, the photographs make him the central figure in a drama not of his making. They should give anyone who knows a child that age an aching rage, knowing how small ones toggle between a brash world-meeting confidence and an urgent need to be held close. Like every moment of early childhood, it is a crucial point of development. The politics behind this scene pervert and twist that development. Staging it for us, Moore makes clear the deeper violence at work.

Whether the boy started at his father’s side or retreated there, I do not want to play the scene forward. I do not want to move ahead to the mylar blankets, green mats, and chain link of the processing center. I do not want to imagine the boy, 72 hours later—in the best case scenario—greeted by a mural of President Trump in a Department of Health and Human Services facility. But I can’t avoid it because I have seen those spaces. I cannot bring myself to picture the little boy there, and I cannot stop myself from seeing him.

I don’t need a picture of the daughter no longer breastfeeding or the toddler pounding her fists in a cage either. There are enough photographs now. We can see the reality and the need to act.

Yes, migrant children also slept in cages during the Obama administration. Yes, there are problems with making the plight of children the primary justification for immigration justice. But right now, photographs seem to be catalyzing political action in a way they do not often do. And it is time to be the grown-ups.

And then, demand immigration justice and foreign policies to ensure that no one—of any age—ends up in a cage.

-Christa J. Olson

Photo 1: U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Rio Grande Valley Sector; Photo 2: HHS Handout / Jacob Soboroff/Twitter Accompanying Tweet: “Here are some photographs of the boys in the cafeteria. This is not a school cafeteria. Hundreds called to eat at a time on rotating shifts. When I told @chrislhayes it felt like a prison or jail, I was thinking about this.”; Photos 3 & 4: John Moore / Getty Images Caption: MISSION, TX – JUNE 12: U.S. Border Patrol agents take a father and son from Honduras into custody near the U.S.-Mexico border on June 12, 2018 near Mission, Texas. The asylum seekers were then sent to a U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) processing center for possible separation. U.S. border authorities are executing the Trump administration’s zero tolerance policy towards undocumented immigrants. U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions also said that domestic and gang violence in immigrants’ country of origin would no longer qualify them for political-asylum status.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus