Notes

Portraits of Retired Sex Workers: The Gaze Turned the Other Way

There is something disorienting about Adriana Zehbrauskas’ photo essay about retired sex workers in Mexico. Zehbrauskas, who wrote the essay and took the photographs for the New York Times, takes us inside Casa Xochiquetzal, a house in downtown Mexico City that has become a retirement home for prostitutes who no longer make their living on the streets.

In the essay, we are simultaneously admitted into the private space of Casa Xochiqutzal and kept at a distance. The women, whose lives have been marked by the most public of professions, confront us head-on and hold us at arm’s length. Public and private collide in the essay and in the lives of the women it profiles.

With only one exception, each photograph in the essays offers us one of two distinct frames for viewing the women of Casa Xochiquetzal. Domestic scenes, dominated by the mustard yellow of the Casa’s walls, appear in landscape and highlight our distance from the women in them. We are inside, but we are not let in. The photograph above makes that point most dramatically. Seeing it, we are not even yet allowed inside the house. Just before this photograph appears in the essay, Zehbrauskas notes, “It is not easy to find the house. It is hidden behind a maze of street vendors. The large wooden doors to the entrance are usually locked. ‘Visitors are only allowed with a previous appointment made by email,’ says a sign out front.”

The photograph duplicates that point and reinforces it. It purports to show us the front door to Casa Xochiquetzal, but only the caption and context let us see it. Shadows, power lines, disintegrating cardboard boxes, and a dark overhang obscure our view. The scene is busy with people, windows, and the stuff of urban life. Though the upper corner of the door is the photograph’s brightest spot, the door is barred by the shadows of three powerlines and a nearby wall. We are not welcome. The way is shut.

The Latin root for the Spanish word “prostituto/a” and English word “prostitute” invokes availability. It means, roughly, “to offer for public sale.” The women of Casa Xochiquetzal made their living by being available in public. In return, their families and communities shunned them, leaving them to make their way in public even after they stopped being able to make their living through sex work. In that conventional frame, they were public women evicted from private space.

Now, in Casa Xochiquetzal, there is a reversal. The domestic scenes—like the entryway photograph and the final photograph of the essay—enforce privacy and hold viewers at bay.

The residents of Casa Xochiquetzal are private women. Unavailable. My initial read of the essay’s last photograph, which features Patricia Robles Orozco alone in her room, was that it isolated her, setting up her present state as pitiable in contrast with her former life as a cabaret star. Ms. Orozco’s slumped posture and bent head certainly corroborate that reading. But I have to catch myself. She is unavailable to me, yes, but that inaccessibility is, itself, an assertion. As Ms. Orozco sits near the window so that light will fall on her work, she is a private subject. She chooses to be no longer available in public.

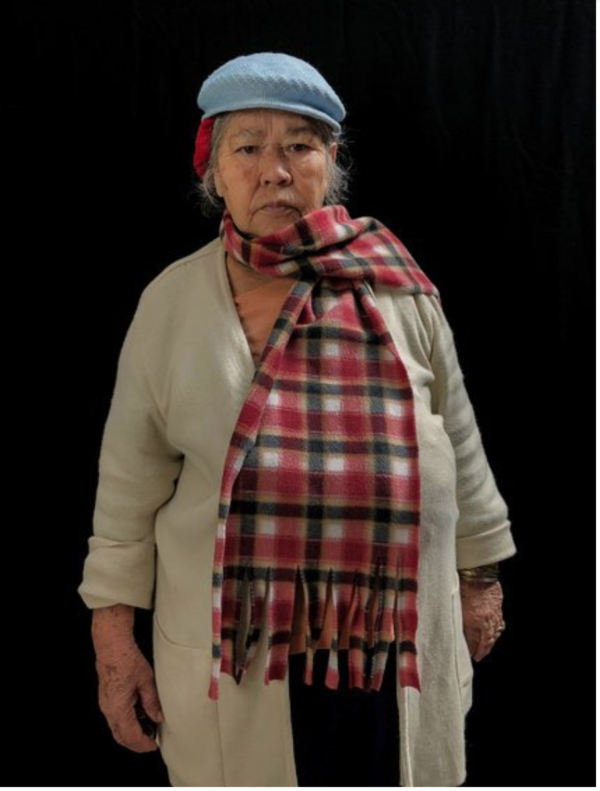

If the domestic scenes emphasize privacy, though, two-thirds of Zehbrauskas’ photographs in the essay take an entirely different tack. These individual portraits, set against a solid black background, put us face to face with the women of Casa Xochiquetzal. They glare at us. Dare us. Challenge us to be publicly available even as they are not.

I will confess to loving these portraits and the quotations that accompany them.

Raquel López Moreno dons a blue cap and frowns out of the frame, her chest and belly thrust forward and draped in a plaid scarf. Her hands—the wrinkled, age-spotted hands of an 81-year-old—hang at her side, but there is no passivity here. “I’m proud. I put my two daughters through school,” she tells us. Damn right she did. Private shame may not disappear; its marks may remain (the fact that Ms. Moreno lives in Casa Xochiquetzal suggests that her daughters may have rejected her), but it is balanced with a distinct sense of public pride. The women of the portraits are not available to us, but demand that we be available to them.

Zehbrauskas’ portraits do not romanticize the lives of sex workers or the realities of making yourself available for public sale.

In their captions, many of the women echo Norma Angélica Sánchez Garduza’s assertion, “I never want to go back to the streets. It’s too hard. You lose your dignity as a human being.” Yet the demands they make in these portraits make clear that they, nevertheless, retain their dignity.

Ms. Garduza is elegant, austere. Her look activates the familiar tropes of Latina allure, but her gaze short-circuits them. Out in public, on the streets, you lose your dignity and your humanity and become the object of others’ desire. Here, in public again but on different terms, Ms. Garduza makes us the objects of her dignified glare.

Adriana Zehbrauskas, Casa Xochiquetzal, and the women in these photographs together trouble the terms of publicity and privacy that are so brutally, poignantly at the center of sex work. Photography inevitably makes its subjects appear available for public consumption—at least on some level. The refusal of that availability makes these images unnerving in the best possible way.

-Christa Olson

Photos: Adriana Zehbrauskas / New York Times; Caption: The house, with its large wooden doors, is hidden behind a maze of street vendors in a Mexico City neighborhood; Caption 2: Patricia Robles Orozco, 68, colored some drawings in her room at Casa Xochiquetzal. She was once a cabaret star; Caption 3: “I’m proud. I put my two daughters through school.” – Raquel López Moreno, 81; Caption 4: “I never want to go back to the streets. It’s too hard. You lose your dignity as a human being.” Norma Angélica Sánchez Garduza, 53.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus