Notes

Is the Face of Contemporary Feminism Still Too Pink and White?

A year ago, I joined other commentators in criticizing the sea of pink hats that pervaded the visual optics of women’s marches in Washington, D.C. and around the world. Pink pussy hats, we argued, hail a universal view of gender that overlooks the lengthy history of racial inequalities within the mainstream feminist movement.

This year, pink hats again dominated the visual landscape of gender-focused protests. Photographs of anniversary marches feature crowds of pink-hatted protesters, as in the picture above from the January 21 Las Vegas rally. Mostly older, white attendees fill the frame, their pink hats echoing far back into the crowd. Is this the face of contemporary feminism?

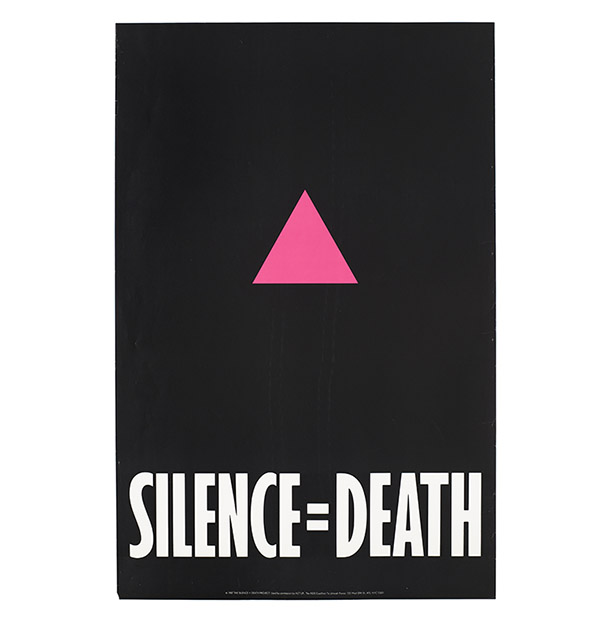

Reclaiming symbols of hatred or inequality has often been an effective strategy to fight oppression. Think of ACT-UP’s famous Silence=Death poster from the 1980s. To protest the failure of the Reagan administration to fund AIDS research, the activist group reclaimed the inverted pink triangle that the Nazis forced male homosexual prisoners to wear. Yet, acts of reclamation rarely operate seamlessly. We have only to think of the heated discussions about the n-word, queer or crip, words that for some signal empowerment while for others reignite painful memories.

The pink pussy hat likewise carries competing, even contradictory, meanings.

For many, “pussy” is an empowering refusal of this misogynist reference to women’s genitals. Unaddressed normative connotations associated with pink, however, haunt this symbol. Associations between binary colors and genders emerged in the early 20th century but clothing designers and toy manufacturers didn’t settle on pink for girls and blue for boys until after WWII.

Popularized most famously by Disney and Mattel, pink is now the preferred color for princesses, fairies and other idealized figures of femininity. As critics point out, racism, ableism and gender normativity shape and constrain this idealized figure – after all, most pink-wearing princesses are conventionally beautiful, female and blonde.

In response to criticisms about the gender normativity and white privilege that plagued last year’s Washington, D.C. march, organizers held this year’s first anniversary rally in Las Vegas. Long a staunchly Republican stronghold, the growing demographic diversity has turned the state purple, making it an apt locale for the optics of inclusiveness.

Social media and news images celebrated the generational, racial, and gender diversity of women who attended the rally and who spoke from the podium (many of whom demanded better accountability and support from white protesters). This photo featured four organizers looking toward the stage where, unseen to the viewer, Congresswoman Maxine Waters addresses the crowd.

Focusing on the organizers rather than the celebrity speaker calls attention to changes in leadership. The embodiment of diversity, the faces of these leaders convey their pride and sense of accomplishment. Taken from below, the viewer gazes up at the women, as if to suggest that they are feminism’s future.

Last year, organizers of the National Women’s March also activated historically fraught relations between sex workers and mainstream feminists when they stated that they “stand in solidarity with all those exploited for sex and labor.” (Those statements were subsequently amended in response to vocal opposition).

Shamed, perhaps, by the existence of 21 legal brothels in Nevada, this year a group of 36 sex workers appeared onstage. The brilliant blue sky in this picture highlights several of them cheering or shouting while holding signs proclaiming their human rights. Similar to the photo of the organizers, the view from below accentuates their empowered stances. While marches may not often result in direct political action, as some critics charge, pictures like these envision the value in collective protest for women from marginalized communities.

Despite the inclusiveness on stage and the visual diversity promoted in news media and blogs, how much of a shift has actually occurred in the mainstream feminist movement?

In scanning hundreds of pictures from protests around the globe, the brilliance of the pink hats scattered throughout the crowd remains the dominant theme. Clearly, for many, pink stands for a shared commitment to gender equality, a commitment that has been effective in generating renewed activism in the Trump era. But, herein lies the dilemma — how to reclaim a symbol so burdened by its own history of racial, gender and able-bodied normativity?

This portrait of a young girl of color at the Las Vegas march suggests another strategy to reclaim meaning. She stands in profile, isolated from the crowd, as she looks solemnly into the distance. Potentially a representative of feminism’s next generation, she wears a pink and purple jacket and hat while a blurred orange, yellow and blue flag attached to her jacket flies behind.

Combining protest symbols is one way to complicate the generalized connotations of pink. However, the history of white privilege is not readily shaken off, not for a young girl looking out at a world that remains racially oppressive. As with the pink triangle, the point may be less about finding a perfect symbol than about remembering the uglier parts of our history even as symbols morph into new meanings.

– By Wendy Kozol

Photo: Roger Kisby/RollingStone.com. Caption: “Looking Up: Protesters packed Las Vegas’ Sam Boyd Stadium – capacity 36,800 – for Sunday’s rally.”; Photo 2: Designed by GranFury Caption: Poster, AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power(ACT UP). Photo 3: PussyHat Project; Photo 4: Rebecca Cook/Reuters; Caption: “Women’s March Co-Chairs Linda Sarsour, Carmen Perez, Tamika Mallory and Bob Bland listened to Congresswoman Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) speak at the Women’s Convention.” Photo 5: Roger Kisby/Rolling Stone.com. Caption: Sex Positive: Many women took the march as an opportunity to shine a light on sex worker rights.” ; Photo 6: Chona Kasinger/W Magazine. Caption: Participants at the Women’s March “Power to the Polls” event on Sunday, January 21st at Sam Boyd Stadium in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus