Notes

Feeling Alt-Right: Hate and Shame In Online Right-Wing Imagery

Images hold a privileged place within the Internet’s economy of attention. Social media platforms rely on the visual to channel worldviews ranging from liberalism to right-wing populism. There is no turning back from an image-based culture: politicians right and left simplify their messages to the citizens; stories posted to Facebook with an image generate more engagement; the most viral tweets generate millions of meme-based responses.

The power of images to shape political landscape has been particularly evident in the current actions of far-right groups, such as the alt-right, white nationalist, and men’s-rights activists manipulating the mainstream media and large audiences alike in order to “red-pill” them (a term derived from the film The Matrix (1999) that refers to alerting the citizens that political correctness, gender and race equality and global human rights are nothing but an illusion). Platforms such as Breitbart, Reddit, Voat, Infowars, VDARE, American Renaissance, Alternative Right or The Right Stuff use images for indoctrination; conspiracy-mongering; Holocaust denial; climate change denial; the promotion of isolationist nationalism, racism, xenophobia and misogyny; and fighting multiculturalism and globalism.

The neo-Nazi blog The Daily Stormer hosts a “memetic Monday,” where community members create images embracing ideas from the openly racist to the mainstream conservative. Pepe, a cartoon frog, entirely co-opted by the white supremacists and transformed into a Nazi militant, is ubiquitous on the “red” Facebook feed.

Recently, an anti-CNN wrestling video tweeted by Donald Trump sparked dismay among the liberals, but also promptly gave alt-right groups a common cause: alt-right Twitter users quickly got #CNNBlackmail to trend; 8chan (a spinoff image-board based on infamous 4chan) trolled targeted CNN journalists; the Daily Stormer made even more anti-CNN memes.

This traffic in the visual has consequences to how we think about photography in general. In Trump’s “post-truth” times, the medium, once recognized for its documentary value, authenticity, “watchdog role,” correctness and truth, now becomes a part of the digital media patchwork, hinting at, rather than chronicling, pseudo-events. These events have no chronology, no development, no beginning or middle, let alone an end. These events are systematically caught up in the power dealings and in attempts to abuse, mystify, and mislead.

War and conflict coverage found online continues to reach back to rich historic and iconographic traditions of photojournalism, while police killings captured by raw, unedited cell-phone videos or crude photographs have become the hallmark of United States visual culture. But what about the images used for populist uses, like unflattering shots if Hillary Clinton? What about Twitter’s racist harassment of Saturday Night Live actress Leslie Jones? What about Trump’s tweet of a photograph of his wife Melania alongside an unfavorable shot of Ted Cruz’s wife Heidi? Can we even consider these images as within the same medium as the one Robert Capa embraced and defined terms?

“A picture is worth a thousand words”@realDonaldTrump@tedcruz#LyingTed#NeverCruz @heidiscruz @MELANIATRUMP pic.twitter.com/dQuoYRprwg

— Don Vito 🇺🇸 (@Don_Vito_08) March 24, 2016

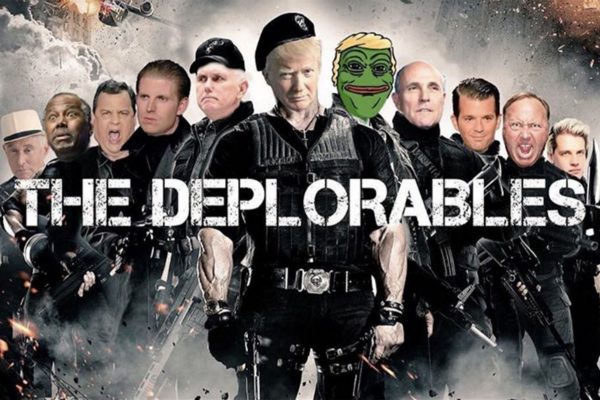

Appropriating, doctoring, and digitally intervening in the photographic image is celebrated rather than shunned, turning photographs into a springboard for other media and for pop-culture references. For example, after Hillary Clinton placed Trump’s supporters in a “basket of deplorables,” Donald Trump Jr. tweeted out a modified image of the poster for the action movie The Expendables with prominent Trump supporters’ faces photoshopped onto those of the action stars, and a cartoon head of Pepe in Trump’s wig.

What remains unchanged is the power of images to spark feelings and shape moods. Shared within (and rarely across) subnetworks of people with common feelings about given issues, online photographs tap into emotional profile of particular political worldview: roughly, into democracy’s empathy and indignation; populism’s anger; fascism’s hatred, patriotism’s love (often abiding with heteronormative, patriarchal and imperialist values, as in the case of white supremacy); conservatism’s nostalgia for lost values; neoliberalism’s sentimentality. The more users share, like, re-blog, retweet, or cross-link images pertaining to issues like gun control, presidential election, same-sex marriage, the Muslim Travel Ban, climate change, the more these images become integral to a customized and participant-regulated network of emotions and feelings.

“The more users share, the more images become integral to a customized and participant-regulated network of emotions and feelings.”

Admittedly, progressives use images for political purposes as well — some recent examples include the Obama/Biden bromance and “But her emails” memes, or the widely photoshopped image of Trump’s family meeting Pope Francis. But the emotional intensity of visual content in the alt-right social media is particularly high. The emotive seems to obliterate the informative here. Feelings, presented to audiences as a radical, universal “hard” truth, are used to fuel and popularize hashtags, spread talking points, and boost news stories coming from prominent media figures; they are the essence of racist, sexist, homophobic, or exploitative images.

Alt-Right imagery amplifies and builds upon audiences’ reactions; they become a sought-after focus of aggressive one-upmanship — how to threaten most effectively? Who can hate more? How to shame successfully? While mimicking, in disturbing symmetry, progressive protest movements such as Black Lives Matter and thus influencing news narratives with trending hashtags, the alt-right exploits photography to intimidate, bully, and ridicule minorities, push the rhetoric of cultural and political abjection, and indoctrinate individuals like Dylann Roof and Elliot Rodger.

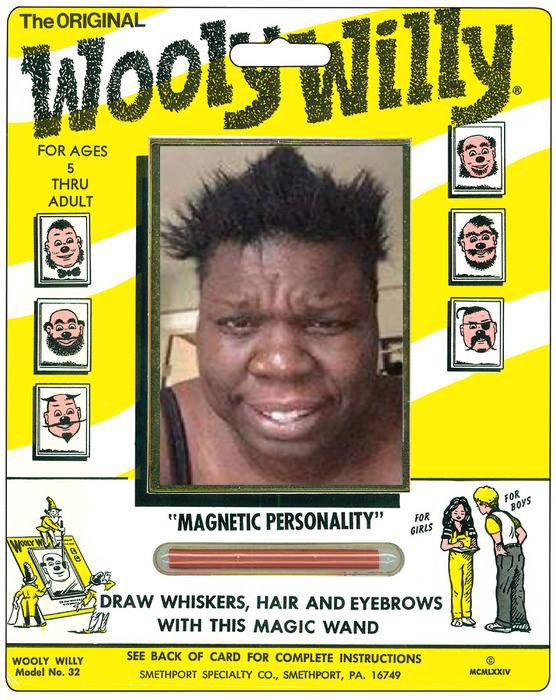

Hate speech goes hand-in-hand with hate images. Accompanied by equally inflammatory, emotionally-charged words (“psycho,” “hate,” “kill,” “bitch,” “crooked”) alt-right photographs are now indistinguishable from policy and info warfare (as exemplified by Trump’s tweets). Some of these images are removed by social media moderators — graphic violence, body damage, sexual assault, or nakedness seem to be the main triggers for moderating content on Facebook, for example. But images might hate in other ways too — faces caught in unflattering, distorted expressions, bodies caught in vulnerable moments, misogyny without undressing, exposure without body damage. I already mentioned some of the frequent targets of the alt-right — Hillary Clinton, Heidi Cruz, Leslie Jones (joined by journalists Megyn Kelly and Mika Brzezinski). All women, all turned into a “political other,” very much in keeping with the trends of Trump’s campaign of hate speech and denigration of women. Non-coincidentally, women featured prominently in the memes of “the crying liberal,” viral among alt-right community in the days immediately following the 2016 US Presidential election.

Additionally, the right-wing extremists and hate groups are remarkably adept at passing hate, anger and contempt as satire. Admittedly, racism and hatred have often been veiled as humor in the visual sphere — the US history of Blackface or ongoing tradition of Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands are examples of when satire is anything but a benevolent or light-hearted rhetoric. But now, it seems, the joke is on the stunned liberal audiences. By pretending to satirically spoof how “soft” and “easily triggered” progressives view conservatives, alt-right meme creators mimic and mock “liberal hysteria.” Any reaction from the left often feeds into the narrative, confirming the stereotype. By presenting itself as a source of casual entertainment, of harmless trolling, photographs found online function as “gateway drugs” to more radical ideas.

“Hate speech goes hand-in-hand with hate images.”

Their playfulness has one more advantage — humor often constitutes a grey zone in the guidelines that social platforms use to distinguish between hate speech and legitimate political expression. Facebook, for example, has developed hundreds of rules, drawing elaborate distinctions between what should and shouldn’t be displayed, designating protected categories based on race, sex, gender identity, religious affiliation, national origin, ethnicity, sexual orientation and serious disability/disease in an effort to make the site a safe place for its nearly 2 billion users. However, when reading Facebook Community Standards, humor seems to be an umbrella term that offers a relatively easy pass for messages that otherwise could be seen as hostile and even dangerous. Many offensive images posted by banter groups and consequently reported by users have remained on the platform after having been labelled “controversial humor” by moderators (see, for example, Alt-Right Memes for Fashy Teens Facebook page).

Images today are perpetually produced, displayed, shared, and fed into algorithms, serving the entangled relationship between visual media and political forces. Photography seems to be affected by these rapidly changing and destabilizing circumstances like no other medium. Whereas for the pre-internet, baby-boom generation photographs were synonymous with the ability to critically question sources, deconstruct opinions, and resist state-imposed ideology, the large majority of images that we encounter on our phones and laptops today seem to have new function: to incite, trigger, offend, and indoctrinate. Re-examining their claims and agendas, and critically re-assessing their emotional impact, might help us acknowledge these two realms and rethink the medium itself.

— Marta J. Zarzycka

Dr. Marta J. Zarzycka is a lecturer at the Center of Women and Gender Studies at the University of Texas, Austin. She is author of Gendered Tropes in War Photography: Mothers, Mourners, Soldiers (Routledge, 2017).

(Photo 1: Source: The Daily Stormer, a self-described “neo-Nazi website which rips-off memes from 4chan and refuses to give them credit.” Photo 2: A still from a GIF created by Reddit user HanA**holeSolo. President Trump tweeted the GIF on July 2nd 2017. Photo 3: Donald Trump Jr. tweeted out a modified image of the poster for the action movie The Expendables with prominent Trump supporters’ faces photoshopped onto those of the action stars, and a cartoon head of Pepe in Trump’s wig. Photo 4: Women featured prominently in the memes of “the crying liberal,” viral among alt-right community in the days immediately following the 2016 US Presidential election. Photo 5: Source: Alt-Right Memes for Fashy Teens Facebook page. Caption: “Is it too late to make memes at the expense of the black ghostbusters woman?”)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus