Notes

Police Killings: On the Decision Not to Watch

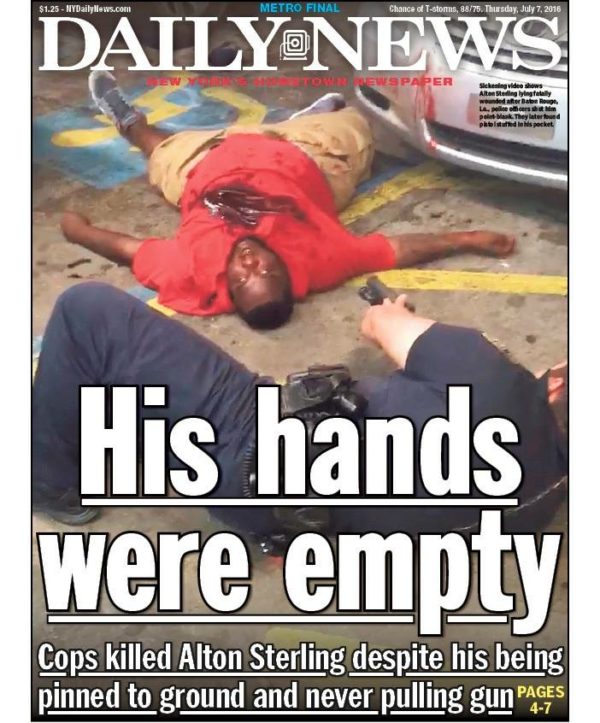

I have not watched the video of Eric Garner gasping “I can’t breathe” as police officers held him. I haven’t watched Alton Sterling being shot by officers outside the Triple S Food Mart, or seen Philando Castile’s life drain away after a routine traffic stop. I have not watched any of the now horrifyingly ubiquitous cell phone videos that show police officers taking black lives. I have stopped at the placeholders, only reading about and imagining what lies beyond that dark or out-of-focus portal. If I choose not to look because these scenes are too much to bear, I am hiding behind my privilege. I am looking, as Michael Eric Dyson says, through a pair of binoculars that allow me to “see black life [and, I would add, black death] from a distance, never with the texture of intimacy.” But though my refusal to watch may be partially a matter of privileged cowardice, there are also a pair of moral questions driving it: Do I have the right to look? Do I have the right to turn away?I can never fully answer those questions, perhaps because the answer to both is yes. And no. Never. Sometimes. And always. Claudia Rankine wrote powerfully about this—with a firm appeal to visibility—in the wake of the terrorist attack on Mother Emmanuel last year.

Leaving the impossible morality of looking hovering over us, though, I want to reflect as well on what it means to be a witness of racist violence, whether or not we watch the videos.

As news feeds fill with scenes of police officers murdering unarmed or non-aggressive men of color we must remind ourselves that these deaths are not new. Thanks to cell phones and social media, more of us see and hear about these deaths, but they have been happening for centuries. People of color in the United States have always disproportionally faced the violence of the state. Now white people are being brought face-to-face with that fact in visual, visceral ways. Of course, today’s videos share a history with Ida B. Wells’ anti-lynching campaign and Mamie Till’s refusal to close her son’s casket. White folks’ appeals to ignorance are disingenuous at best.

These videos initially offered a new hope that justice might be served and the state be held accountable for its violence. That hope has been repeatedly dashed. Seeing may be believing, but it has not been sufficient to overcome the apathy of white privilege and the sediment of institutional racism. So we must consider what it means to look in the absence of immediate justice. We must accept witnessing as fraught territory that brings with it varying impact, consequences, and obligations.

First, there is the horrible and horrifying bravery of the on-site witnesses, especially the ones who exercise their right to record. The toll and the courage this sort of witnessing demands has been brought into stark relief this past week by the extraordinary nature of Diamond “Lavish” Reynolds’ video of her fiancé, Philando Castile, dying. Forced to watch as her beloved bled, she was given no choice but to see. In this case, having to look was a sort of punishment, an act of terrorism against her. Her amazing, powerful choice to show what happened, to make it public, answered that violence with witness (a fact eloquently explored by James Poniewozik this past Thursday). When I read of Ms. Reynolds’ act, I cannot help but hear the echoes of Mamie Till’s voice saying, “Let the world see what I’ve seen,” turning terror into action. And Ms. Reynolds has continued to witness, her image and words recorded on cell phones and circulating on social media.

Next, there is the unforgivable and almost unimaginable witness of Ms. Reynolds’ four-year-old daughter. Her voice, her presence in the video tells us that such violence is indeed imaginable. All too much so. She saw. She also was forced to watch. I can think of nothing that would make such seeing anything other than an assault, an utterly destructive violation of her human rights. Likewise, Mr. Castile’s family and friends—and perhaps all African Americans—as they watch (or imagine) his death, both witness and are assaulted. The violence seen is another act of violence done to them.

Then there are the officials—the investigators, the district attorneys, the justice department, the politicians. They must witness, and they must act (or we must push them to act). It may even be that they must watch the actual video. When the interim chief of the St. Anthony police said that he had not seen the video, he implicitly called into question his obligation to see what had happened and so attempted to side-step the indictment that Ms. Reynolds’ witnessing called down upon him. In such cases, saying “I haven’t watched the video” is an indefensible refusal to witness.

And finally, there are the rest of us. Those who witness at a distance, for whom Philandro Castile and Alton Sterling join a growing list of Black men and women who have lost their lives—on camera—at the hands of police officers. We are the audience for the heroic, horrifying images made by people like Ms. Reynolds. We are the ones who must be called out of complacency by their urgency. We do not need to actually see the blood flowing to be obligated as witnesses. Ultimately, our responsibility (especially those of us who are white) is to not need to see racist violence in order to believe that it exists. Whether we watch the videos or not, witnessing requires us to acknowledge that racist violence is there to be seen. It demands we recognize that racist violence is there, seen or unseen. Most importantly, it insists that we take concrete action to ensure that it ends.

— Christa Olson | @christajolson

(photo 1: Screenshot of the placeholder for Diamond “Lavish” Reynolds’ Facebook video. photo 2: Eric Miller/Reuters; caption: Diamond “Lavish” Reynolds is recorded on a cell phone as she recounts the fatal shooting of her boyfriend, Philando Castile, by police during a traffic stop Wednesday night. )

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus