Notes

35 Cosby Accusers Featured at NY Mag: How the Photography Stands Up to Rape Culture

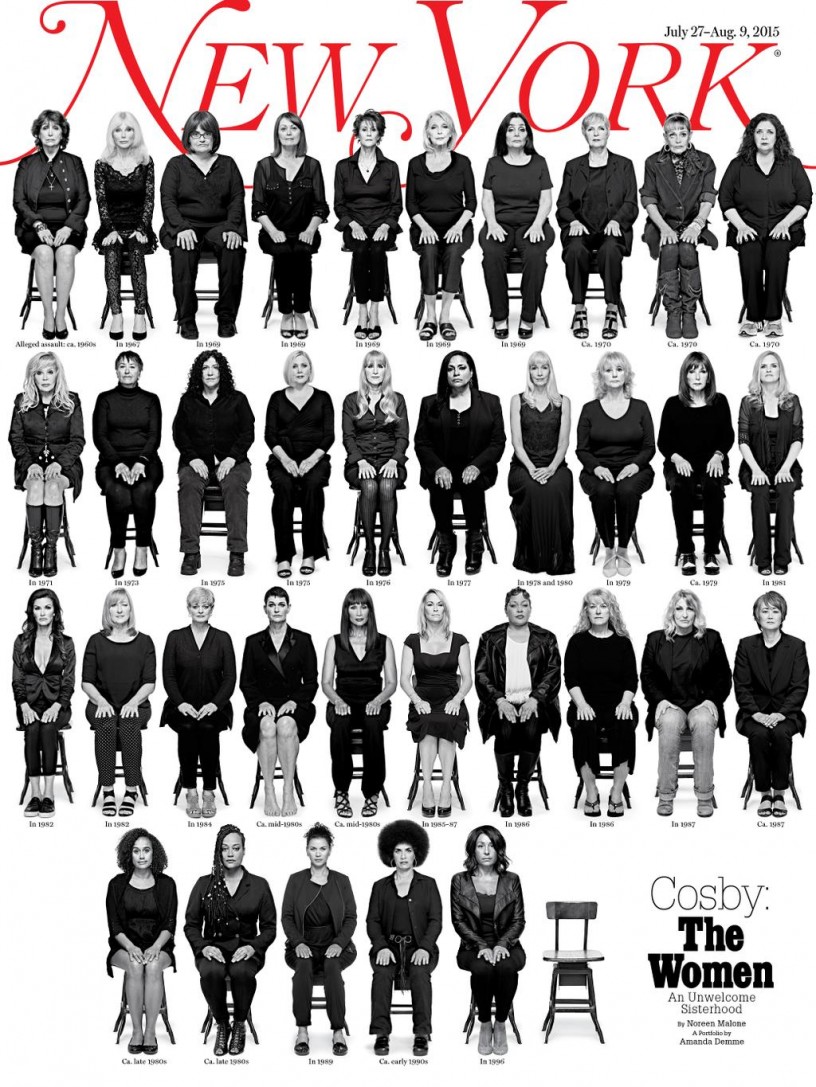

The New York magazine cover featuring images of 35 women willing to tell their stories of how Bill Cosby intimidated, drugged, sexually assaulted, and/or raped them has become “instantly iconic.” Lauded across the media for its power (see, for example, Vox, Vanity Fair,Mother Jones, and USA Today), the montage indicts Cosby and (quoting the article’s headline) “the culture that wouldn’t listen” to his accusers.

The cover and the feature’s accompanying portraits are stellar examples of how to use photo narratives to stand up to rape culture. First, the cover image is black and white. Acquaintance rapes are often treated as crimes with a lot of gray area— “he said/she said” scenarios in which truth is ultimately unknowable. This photo asserts that the case against Cosby is clear—spelled out for readers, visually and verbally, in black and white.

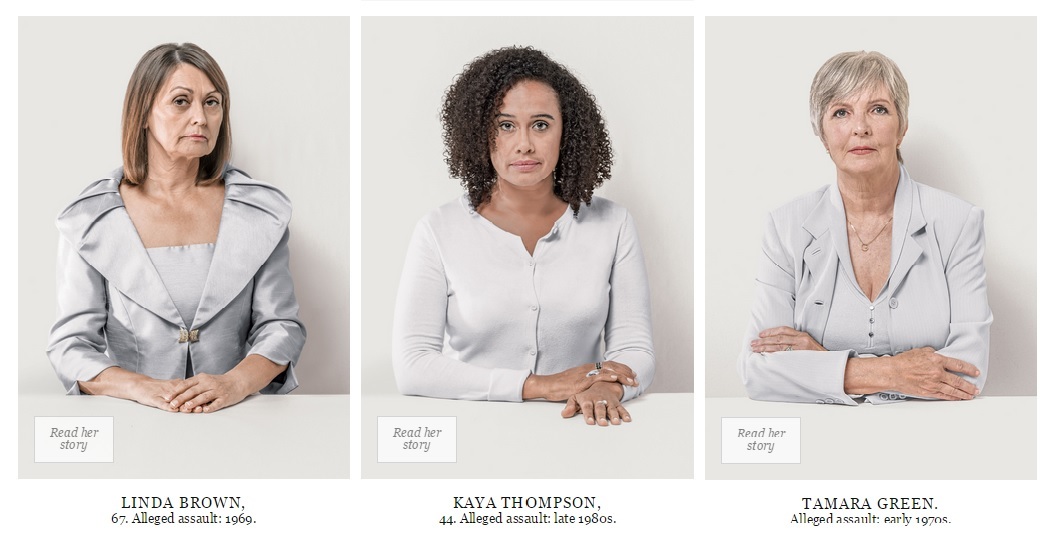

The black-and-white theme continues in the individual portraits of the accusers featured throughout the piece.

Each woman poses in white or silver and is photographed against a white background, with the color serving as a visual metaphor for innocence, honesty, and purity—characteristics which too often are not associated with victims of acquaintance rape.

There is another way in which the black-and-white motif is consequential for this story. During his years as an alleged serial rapist, Cosby victimized a diverse range of women of various ethnicities, ages, and occupations. Recent discussions of the ways in which black and white Americans are treated very differently by the police and the U.S. criminal justice system have underscored the fact that there are two Americas—one that reflects the experiences and perspectives of white Americans and another that reflects those of non-white Americans. This New York cover illustrates that, unlike other places in U.S. society, the sphere containing victims of rape and sexual assault is fully integrated. Of course, that does not mean that race has no bearing on how even women in very similar circumstances who were violated by the same perpetrator experience their attack.

In her narrative, Jewel Allison recounts why the prospect of publicly accusing Cosby of his crime was particularly gut wrenching for her as an African American woman, saying:

I also had the extra burden of not really wanting to take an African-American man down. I’ve always been very closely involved in the black community. And for me to come forward and basically destroy this very positive image of, as few as we have, of African-American men in America, it was just too difficult to do at that time.

In addition to its black-and-white composition, the cover image is impactful because it simultaneously conveys the scope of the problem and its individual consequences—a characteristic that extends to Noreen Malone’s reporting and Amanda Demme’s individual portraits. Cosby victimized many women, and although their stories share telling similarities, each woman is unique.

Sadly, one (or two or three) unique stories from individual women were not enough to convict Cosby in either a real court or the court of public opinion. As the timeline assembled by Vulture’s Matt Giles and Nate Jones attests, many of the allegations recounted in the New York story have been on public record for some time. One wonders what the tipping point is—how many women have to accuse the same man of sexual assault before they are believed? Three was not enough, but apparently, thirty-five is. In its coverage of the New York cover story, a Fox News correspondent calls the piece “shocking.” But by now no one should be shocked by the details of this story, which was whispered about for decades and has been covered in earnest by national journalists for nearly a year.

It should be noted that although the presence of multiple accusers (and their visual depiction in a group) is being credited as the reason the accusations are suddenly seen as credible, even undeniable—Think Progress announced that “One Extraordinary Magazine Cover Could Finally End Bill Cosby’s Public Relations Offensive”—it is, regrettably, not the collective word of these women that convinced most journalists and the public at large of Cosby’s guilt. It was the words of two men.

The matter failed to garner much attention at all until comedian Hannibal Buress mentioned it in his act, something that prompted accuser Barbara Bowman to write (in a Washington Post op-ed), “only after a man, Hannibal Buress, called Bill Cosby a rapist in a comedy act last month did the public outcry begin in earnest.” More damning is the fact that Cosby apologists were still plentiful until word leaked that Cosby, himself, had admitted in a 2005 deposition to giving women Quaaludes prior to initiating sex. So, perhaps even thirty-five female accusers is not enough, absent one man’s confession.

That is why New York magazine’s choice to indict not only Cosby but rape culture, more broadly, is important. The women portrayed on the cover are pictured seated in chairs, creating a digital witness stand from which they may tell their stories. (Sadly, due to statutes of limitation, it’s the only witness stand from which most women will be able to testify.) The women look straight ahead, directing their calm, resolute, and confident gaze at the reader/viewer. That visual choice led many media outlets to refer to the women as “accusers” rather than as “victims,” a frame that dignifies women and imbues them with power.

Additionally, these women are unlike anything we are used to seeing on the cover of magazines. They are real women whose images (at least in the cover photo) do not appear to have been heavily retouched or altered for aesthetic or artistic purposes. The fact that an image like this is jarring illustrates how seldom women are pictured as authentic individuals with personal agency on the newsstand.

The choice to depict specific individuals and tell their stories also indicates the beginning of a cultural shift with respect to victims of sexual violence. Historically, it has been a media best practice to keep the identities of victims of sexual violence a secret. This requisite shield of privacy, however, is a conspicuous marker of the rape culture that shames victims more than perpetrators. Of course, if victims do not want to be named, their privacy should be respected. But in order to truly undermine the “blame and shame” frame, not only do victims of sexual assault need to speak out as accusers, but the media needs to be willing to tell their stories in a way that respects their dignity.

The New York story made two final visual choices that effectively highlight the problem at hand. First, they included an empty chair at the end of their cover montage, signifying women who have not come forward or do not want to go public with their story. The empty chair reminds us that there are many faceless victims of sexual violence (according to the Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network, 1 out of every 6 American women has been the victim of “an attempted or completed rape in her lifetime”) and rape culture continues to suppress their voices. One immediate response to the cover story was the #EmptyChair Twitter hashtag people used to discuss their experiences with sexual violence, extending the positive impact of the story by adding narratives of other accusers, revealing the damage done by other perpetrators, and indicting anyone who has been a bystander in their own daily lives.

Finally, the portraits visually illustrate what the narratives confirm: each encounter affects each individual differently. Although we cannot be sure if the women chose their portrait poses themselves, or if they were given direction by the photographer, there is a diversity of expressions and orientations toward the lens that communicate different frames of mind. Some women gaze forcefully ahead as they did in the cover pose. Others look away from the camera. Others have a downward gaze.

What the New York magazine cover story and each individual portrait asks the viewer to do, however, is to look at the strength, courage, and grace of women who speak out against sexual violence and the cultural misogyny that encourages us not to believe individual women. As individuals, we each have the power, and the responsibility, to call out rape culture and its many manifestations. The question is, will we? That would be powerful.

— Karrin Anderson | @KVAnderson

(photos: Amanda Demme/New York magazine. captions: photo 2: Linda Brown, 67, Alleged assault: 1969; photo 3: Kaya Thompson, 44, Alleged assault: late 1980s; photo 4: Tamara Green, Alleged assault: early 1970s; photo 5: Jewel Allison, Alleged assault: late 1980s; photo 6: Barbara Bowman, 48. Alleged assaults: 1985-1987)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus