Notes

I Wanted to Like that NYT Photo Essay About Growing up with Gay Parents

I wanted to like the photo essay “What Could Gay Marriage Mean for the Kids?” in the recent New York Times Sunday Review. I really did. For one thing, I have a personal investment in the question: my partner and I—gay married until the Supreme Court says otherwise—are raising a toddler, and I’d like to believe she’s going to be okay. On the whole, the studies I’ve seen suggest that she will be. And, visually, maybe I’ve gotten a little too used to the sappy-sweet celebrations of gay family life that have become standard fodder on liberal social media feeds.

So, I wasn’t prepared for the gut punch that came along with Gabriela Herman’s fourteen portraits featuring adult children of gay parents. Taken one-by-one, the photographs capture strong, thoughtful young adults in moments of solitude. Cumulatively, though, the series takes on an inescapable sense of sorrow and isolation, and not just because of captions that frequently emphasize the subjects’ struggles with their parents’ identities. As a [gay] parent viewing the photo essay, I felt a rush of defensiveness and worry. As a scholar of visual rhetoric, I wanted to understand why. What was it about these photographs that so set me on edge?

After a hard look, it finally came clear to me: This photo essay explores the difficulty of having a gay parent in the 80s, 90s, and early 00s. As a reflection on what gay marriage means for today’s generation of kids, though, it is (I hope) rather out of date.

Herman’s photo essay combines therapeutic personal narrative, incipient activism, and social analysis. Of the three, the theme of therapy is the strongest. More often than not, the portraits frame their adult subjects as in recovery, using all the conventions of post-trauma photography: solitary figures, haunted gazes, romantic lighting, sparse domestic spaces. As a viewer, I ache for these adults and for the children they once were. Ache, however, is not the feeling I want to have in response to the title’s loaded question about the future, “What could gay marriage mean for the kids?”

The disjunction between the title’s forward-looking question and the trope of past trauma is perhaps most palpable in the first portrait after the essay’s opening text. In it, Zach Wahls—the young man whose impassioned speech in defense of his family went viral in 2011—lies on a blue couch, his head propped on a rust-colored pillow. Wahls gazes mournfully at the camera, his hands clasped on his stomach, his scant beard elegantly untrimmed. The room behind him is dark, and a warm light falls on the couch and across his body. So much about the photograph evokes a psychoanalytic encounter, and it sets the tone for the essay’s larger visual therapy session.

The melancholy of Wahls’ portrait is only enhanced by its contrast with the other public picture we have of him: that of a clean-shaven college student in an almost-tailored suit, speaking confidently before the Iowa House of Representatives. For all their strength and dignity, there’s little doubt that Wahls and the other men and women in the NY Times Magazine essay have painful stories that have shaped their past and their present. Still, that earlier media image had Wahls closing his speech with the words:

“The sexual orientation of my parents has had zero effect on the content of my character.”

If character and mental health are not perfectly correlated, it’s still not a statement that lends one to visualize a treatment situation.

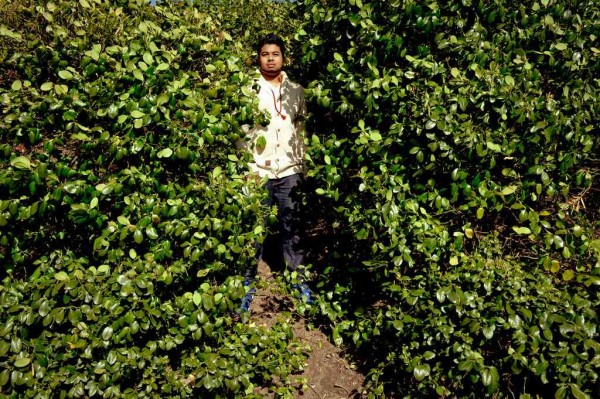

Taken as a whole, the portraits show isolated adults in empty rooms, abandoned playgrounds, and vacant streets, sometimes half-hidden by curtains or shadows. Some stare resolutely at the camera as if to demand recognition and redress, like the photo leading this post.

Others look into the distance, starkly alone with their memories. Soft light highlights faces and hands—these are gentle people who have emerged whole from challenging childhoods. They clearly have the photographer’s sympathy, and gain the viewer’s as well.

While sympathy is a powerful emotion, however, it sits awkwardly with the task this photo essay sets for itself with its provocative title and subtitle:

“What could Gay Marriage Mean for the Kids?: When courts consider same-sex unions, they often ask about what life is like for children with gay parents. Here are some answers.”

These photographs are answers, but not to the title as written. Instead, they answer the question, “what was it like to be the child of a gay parent at the end of the twentieth century, well before gay marriage was a viable possibility in the United States?” The photographs give a clear and sad answer to that question. They emphasize the trauma of social isolation and discrimination; they highlight the challenge of growing up different from your peers.

Ultimately, then, the photo essay shares the experiences of a generation of kids born after LGBT people started coming out en masse but well before the recent wave of public acceptance (for lesbians and gay men who don’t rock the societal boat too much). These aren’t pictures of the children of gay marriage; they’re pictures of people who grey up in a world hostile to gay people and their families. That hostility isn’t entirely gone, and marriage rights won’t make it magically disappear. Still, these photographs are reminders of how important it is to work toward a better future, not predictions of gay marriage’s future.

So now I understand the gut-punch a bit better: In these photographs, we see strong, self-possessed adults who are also deeply haunted by their experiences as part of gay families. If that is what gay marriage could mean for kids today, that gives Justice Scalia rounds of ammunition that I’d prefer he not have.

— Christa Olson

(photos: Gabriela Herman for the New York Times Sunday Review)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus