Notes

Behind the Niqab: The (Male) Photographer’s Perspective of Life Through the Veil – Part 1

In this first of two posts, contributor Karrin Anderson reviews photo stories by male photographers imagining what it’s like for Muslim women to experience life through a veil. See the second post here.

Hassan Ammar’s depiction of the view from behind a niqab is designed as an exercise in perspective-taking. Ammar explains that he “decided to begin shooting images through a full niqab to offer a glimpse of what it must be like to look through them.” Of course, photography is all about perspective, and one’s perspectives (political, religious, gendered) certainly complicate how images like these are understood. Explicitly, Ammar states that although “for most, the niqab is a choice,” he is concerned about women in Syria and Iraq who are being compelled by “the extremist Islamic State group . . . to wear the niqab.” Ammar explains, “That means those women now see the world differently than they did before.”

I applaud Ammar for his concern for the women being savagely brutalized by ISIS—compulsory veiling is, sadly, one of the less onerous of ISIS’s misogynistic dictates. But it’s interesting that it took their physical constriction of view to prompt this photojournalist to ruminate on the fact that, as a man, he lacks insight into how women’s perspectives on the world may be very different from his own. That truth is consistent whether you are talking about assessing a sunset through a veil or gauging potential threats in a dark parking lot. Men would do well to consider women’s perspectives more often—not just when there is a physical reminder that your literal view on the world is affected by your gender.

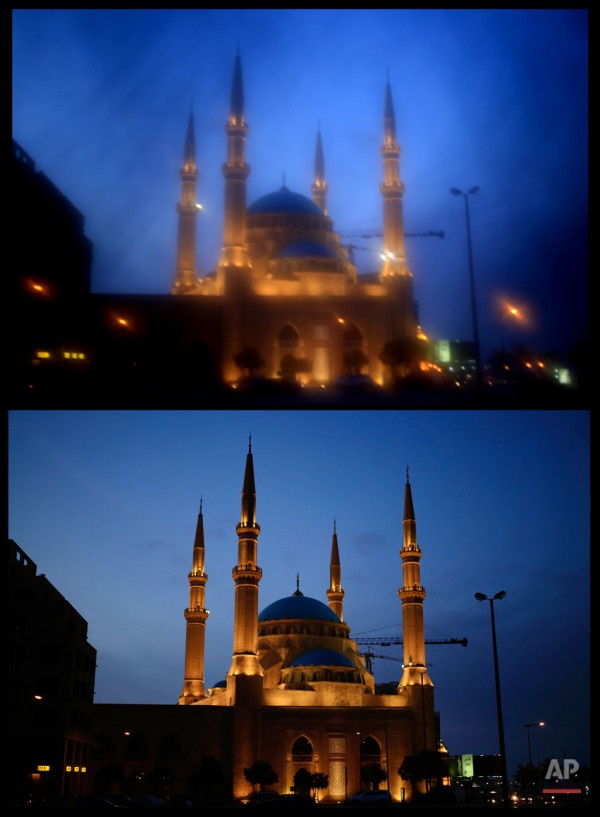

The view that Ammar’s photo spread displays is a dim, blurry, and truncated perspective consonant with his concern for women under siege.

The fully-veiled individual is less able to apprehend the vibrant colors we associate with celebration and play. Her view of everything from the smiles on her children’s faces to the beauty of nature is blunted—shrouded (in this case) in black. It is as if one is thrust into a state of perpetual mourning.

The subject’s restricted peripheral vision makes everyday activities like negotiating a busy city street more difficult and potentially dangerous.

Clarity of vision, something that is literally connected to artistic expression and figuratively associated with leadership, is sacrificed, suggesting that women need not apply for vocations and professions that might require an acute, expanded, or unobstructed view.

That is why stressing that most women don these types of veils voluntarily is a potentially problematic stance. It’s true that in many countries women wear niqabs without threats of legal punishment or death; however, to assert, as does Ammar, that “for most, the niqab is a choice,” glosses over the ways in which women are compelled by religious tradition, family expectation, or societal convention to adopt a religious practice that is so confining and restrictive, it would never have survived as a requisite sign of religious piety had men been required to participate. The Quran instructs both women and men to “lower their gaze and guard their modesty.” If the goal is reducing the likelihood that men will lust after women, doesn’t it make as much sense for them to use a veil to curtail their own gaze as it does to enshroud women in perpetual darkness?

One image in Ammar’s collection is a particularly powerful juxtaposition of women’s spirit and the potential impact of compulsory veiling. This image appears to capture a girl who is too young to be required to veil. She jumps freely on a beach, while the subject behind the veiled lens, perhaps mourning her own lost childhood, takes in a muted version of the child’s joy. The photo seems to convey that this potential for unmediated, unconstrained happiness is quashed by apparel that not only would make it hard to jump freely on a beach, but also makes it difficult to even apprehend the joys associated with that kind of freedom.

Of course, this perspective on veiling is not without its own challenges. Perhaps the preceding reading of the photo is little more than ethnocentric projection—suggesting that someone dressed in Western fashion with hair flowing freely is more personally and spiritually free than someone in a niqab. Some Western societies (France, most notably) have legislated against voluntary veiling, prohibiting women who might choose to cover from doing so. As I have argued on this blog, that, too, is antifeminist and a violation of women’s fundamental human rights. In both cases, men are assuming that their perspective on religion, law, and politics supersedes that of women. What we need are laws that recognize women’s right to self-determination, even when exercising that right might place a woman at odds with the conventions of her community.

Veiling is an important and complex issue. Compulsory veiling does do actual harm, so the project of understanding the perspective of women forced to cover is a worthwhile one. But we must not lose sight of the need to pull back the veil on the issue of global misogyny. That’s the problem that is routinely obfuscated by dominant perspectives.

— Karrin Anderson | @KVAnderson

(photo 1: Hassan Amar/AP. caption: This Friday, May 1, 2015 shows a 32-year-old Lebanese woman, whose father is a Shiite Muslim and mother is a Sunni Muslim, posing for a photograph, on the roof of her home in Beirut, Lebanan. For Most, the niqab is a choice. They do so out of their own interpretation of the Quran and the hadith, a collection of traditions and anecdotes about the Prophet Muhammad, believing that a woman’s body should be covered out of modesty; photo 2: Hassan Amar/AP. caption: This Thursday, April 20, 2015 image shows women walking on the Corniche, or waterfront promenade in Beirut, Lebanon. This photo was shot through the lowered veil of a niqab, which is worn by some conservative Muslim women. photo 3: Hassan Amar/AP. caption: This Saturday, April 25, 2015 image shows girls celebrating a birthday at home in Beirut, Lebanon. This photo was shot through the lowered veil of a niqab, which is worn by some conservative Muslim women; photo 4: Hassan Amar/AP. caption: This Thursday, April 30, 2015 photo shows Lebanese citizens walking on the Corniche, or waterfront promenade in Beruit, Lebanon. This photo was shot through the lowered veil of a niqab, which is worn by some conservative Muslim women; photo 5: Hassan Amar/AP. caption: In this combination of two photos taken on Sunday, May 3, 2015 show [sic] the Muhammad al-Amin Mosque, in downtown Beirut, Lebanon. The photo, top, was shot through the lowered veil of a niqab, which is worn by some conservative Muslim women. The cloth allows women to follow a strict interpretation of their religious beliefs by preventing others from seeing their faces; photo 6: Hassan Amar/AP. caption: This Sunday, May 3, 2015 photo, shows a girl jumping at the public beach of Ramlet alBayda in Beirut, Lebanon. This photo was shot through the lowered veil of a niqab, which is worn by some conservative Muslim women.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus