Notes

Light Over Time: Picturing Appalachia — by Roger May

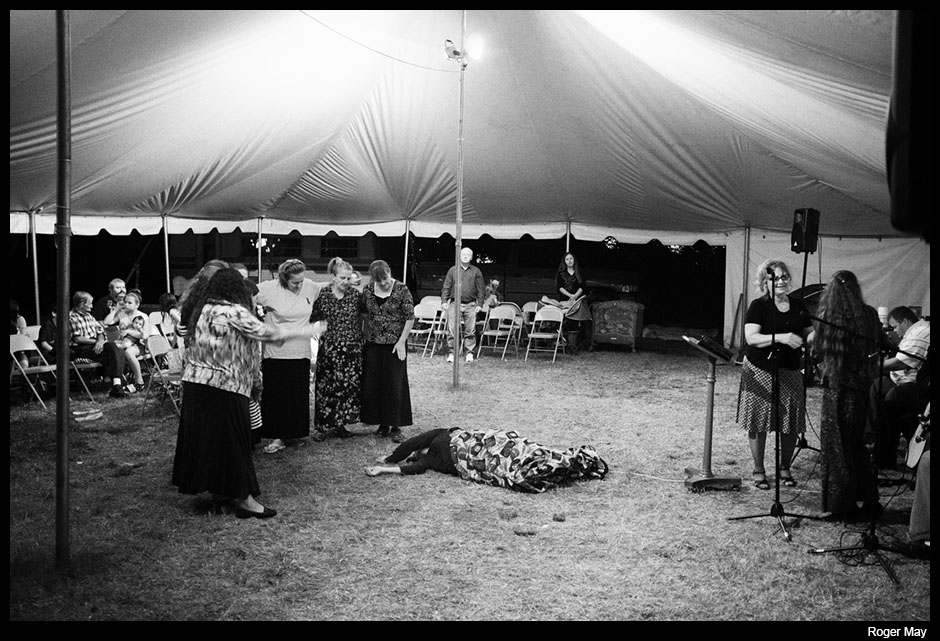

Ladies surround a sister who is slain in the spirit during a tent revival service in Goody, Kentucky, 19 July 2014.

The effort to clarify our sight cannot begin in the society, but only in the eye and in the mind. It is a spiritual quest, not a political function. Each man must confront the world alone, and learn to see it for himself: “first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast the mote out of thy brother’s eye.

— Wendell Berry, “The Unforeseen Wilderness.”

In 1969, an 18 year-old Ken Light found himself in southeastern Ohio being drawn to the social and political activism of the era. Regionally, the United Mines Workers of America (UMWA) was in the midst of dealing with massive internal corruption on an unprecedented scale. Light was asked to be a poll watcher for an upcoming UMWA vote and the experience had a profound impact on him well before he picked up a camera.

Months later, Light began photographing a shoe factory, drawn to the work ethic of the people he met there and their stories. “I learned to be a photographer in Appalachia,” he shared. Aware of Robert Kennedy’s campaigning in Appalachia and Paul Fusco’s pictures in LOOK magazine, Light noticed what he described as a certain invisibility to the social needs and untold stories of Appalachia.

Now, more than four decades later, Light is a professor at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism and directs its Center for Photography. He works to engage his students by encouraging them to look deeper into their own world. Challenged by the barrage of images circulating by social media today, Light is thankful he wasn’t distracted by Facebook, Twitter, and the like as a young photographer. Much has changed since 1969, but Light acknowledges some changes are slower. “It takes generations of trying to change these things (social justice, labor rights, etc.) As photographers, we have a really important role in witnessing what’s going on.”

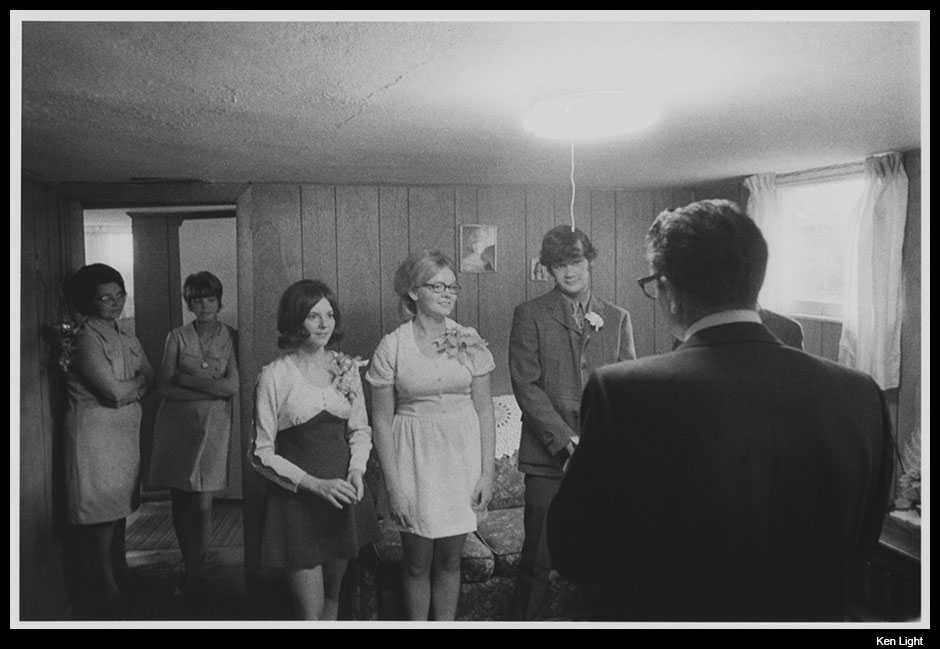

Wedding, factory worker, Nelsonville, Ohio 1972.

I spoke with Light about how we look at place, both in relation to the “Looking at Appalachia” project I’m directing and how he sees his Appalachia work included in the book project, What’s Going On: America 1969-1974.

Two images stand out from Light’s project. One is of a small wedding of two incredibly young folk as two women stand in the doorway with somewhat disapproving looks on their faces. The other is of a man and a young boy standing beside their house with long shadows cast on it.

These are images I could see being a part of the project today. In the first photo we see a small, living room wedding in all its teenage awkwardness and nervousness. Two women, standing in the doorway, look on somewhat disapprovingly, arms crossed at their waists, undoubtedly thinking about similar weddings they’ve observed or taken part in. The groom looks on with a confidence that is likely more about the honeymoon than the rest of his life as a married man while the bride and bridesmaid hold possibility and nervousness in their expressions. This quiet and tender moment was played out thousands of times in small churches, backyards, and living rooms and was captured here with the sensitivity of extended family. Light was similar in age to the bride and groom when he made this picture, yet the style nods to a much more mature and nuanced way of looking.

Father and son, Appalachia, 1971.

In the photo of the man and a young boy with the long shadows, the boy appears to be mimicking the man, but a closer look reveals the man adjusting his shirt while the young boy stands authoritatively behind him, hands on hips.

This photograph stands out as a moment in and of itself, unlike many moments recorded in the late 1960’s of extreme poverty and third world conditions. I wasn’t immediately drawn to the peeling paint, the rough stone foundation, or the peeling siding, but the moment unfolding before the lens. These figures, the same, but different, are composed and delivered quietly, gracefully. These images were made in a style that I find very familiar, a traditional documentary style that isn’t confrontational. Rather, it’s a listening style, one that requires you being present for more than a day or two. This is the kind of work that takes time.

Ken Light is and has always been a social documentary photographer, functioning in or reacting to the political environment. In contrast, I see my own work as very much the type of spiritual quest Berry writes about in his essay. My work in general is not about reacting to political unrest, but rather waiting, looking, listening to quieter moments that don’t often present themselves to be photographed. Light photographed where he was, and I photograph where I am.

The Looking at Appalachia project came about after I came to the realization that it just wasn’t possible to do the project myself. I wanted to personally explore the entire region and photograph as much of it as I could in 2014 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of “the war on poverty.” It didn’t take long to realize that between my family and my day job, it just wouldn’t be possible to undertake such an enormous project. Besides, one person’s perspective on the region would be far too similar to what we’re all accustomed to by mass media; a narrow view on a region far more complex and nuanced that many folks take the time to show. With those realizations, I thought crowdsourcing the project would be a way to get a lot of folks involved and to attempt to see Appalachia as this greater woven-together tapestry of people and place.

In looking at these images by Ken Light I’m thinking about my most recent body of work, “Glory.” As far back as I can remember, I’ve wanted to photograph a tent revival. There was an indescribable draw to this openly public, yet immensely private experience. I was raised in the hellfire and brimstone religious tradition of central Appalachia, so it feels familiar to me.

A handmade sign points to the direction of the tent revival opening the night of August 2, 2014, in Baisden, West Virginia.

The tent revival pictures were opened up to me, like a gift, because that’s what those moments were and continue to be – a gift. I was welcomed in, enveloped in hospitality and allowed to share the experience of the congregation. This gift was offered to me (I believe) because of my quiet approach to making work. I didn’t impose, I didn’t exercise my right to photograph people in a public space, and I didn’t draw attention to myself (aside from the first few minutes of everyone trying to figure out who I was). The moment, the experience, the service belonged to them and I simply wanted to listen and share.

The laying on of hands. Brother Roger Stevens prays for a woman during a service in Baisden, West Virginia, August 2, 2014.

In a way, I wanted to reconnect with my granddad. He was a preacher, a miner, a brick mason, a soldier, and many other things. He was the man who raised me like a son, taught me how to walk quietly in the woods, and the importance of listening. “You have to ears and one mouth and that means you should listen twice as much as you talk,” he would say.

So, there in that tent last July under a parking east Kentucky sky, I listened and spoke little. As I pulled up in the parking lot, I say with my windows down, listening to the music coming from under the tent reverberate off the surrounding hills. I noticed a man stand up and come out from under the tent and make a beeline to my truck, where upon arrival he reached through my window and shook my hand, inviting me to join them all in one continuous motion. I told him I was from the area and had always wanted to photograph a tent revival but that I didn’t want to intrude. Gripping my hand again he said, “Honey, you can take pictures of anything you want. You’re welcome here.”

A young girl sits quietly during a sermon by Brother Roger Stevens in Goody, Kentucky, July 19, 2014.

And with that, I was under the tent feeling the vibration of the music, the hand clapping, and the amen shouts. After a few minutes of sizing me up and trying to figure out who I was and why I was there, everyone settled back in to the service except a few small children intent on making faces at me. It was an amazing experience and as I raised my camera to begin making pictures, I became aware of the goosebumps on the back of my neck and my arms. And just like when I was a child, I followed every word out of the pastor’s mouth, his delivery jarring my memory. I suppose somewhere between the sweat, the shouting, the amens, and the holy ghost, I connected with my granddad. I felt him and something bigger than him, bigger than all of us. I reckon that’s what can happen when we listen more than we talk.

Light’s early Appalachia work is important in that it was intended to shed light on labor corruption and poor working conditions of miners in the region. It was a fixed point in time, which addressed a very real and important issue facing workers everywhere. Light moved on, taking that same social documentary style to death row in Texas, the Mississippi Delta, and many other places. I’m not interested in making pictures anywhere else. I can spend the rest of my life making work here and not even scratch the surface. But what I can do is listen and listen more. I can make photographs and share stories that I hope will celebrate what is unique about Appalachia and also not shy away from what requires hard work to change.

Ken Light is currently running a Kickstarter campaign for his forthcoming book, What’s Going On: America 1969-1974. Photographer Roger May lives in Raleigh, North Carolina and directs the “Looking at Appalachia” project.

The Wendell Berry essay was published in, “The Education of a Photographer,” edited by Charles H. Traub, Steven Heller, and Adam B. Bell. Allworth Press, 2006.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus