Notes

The Cartoonist's Response to the Terrorist Attack on Charlie Hebdo (and How Hard it is to Take a Joke)

The sphere was awash in cartoons and illustrations yesterday in response to the lethal attack on the French political cartoonist and satirist publication, Charlie Hebdo. This is a summary of the primary examples with some thoughts.

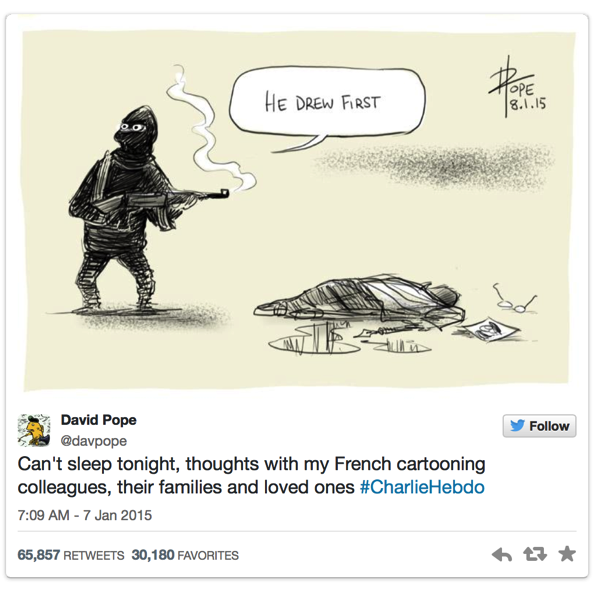

The Pope cartoon was perhaps the most widely published. In contrast to the provocative tone of most Hebdo cartoons, it was actually the most editorial. In eloquent fashion and with great sadness and humanity (the terrorist looks simultaneously vindictive, shocked and defensive), it articulates how the Hebdo cartoons were not just aggressive but were perceived as much by the likes of al Qaeda. At the same time, it captures the fact that the drawings were merely that.

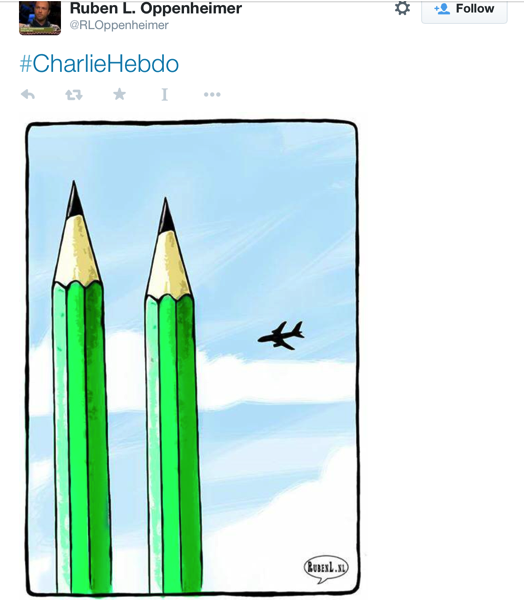

The art of terror involves a high degree of creativity. Capturing a moment and choosing a distinctive target, the attack yesterday was grotesquely brilliant. The scale of Ruben Oppenheimer’s drawing is not hyperbole. To the extent the attack on the World Trade Center set a benchmark, this was similarly time-stopping and will likely be perceived as France’s 9/11.

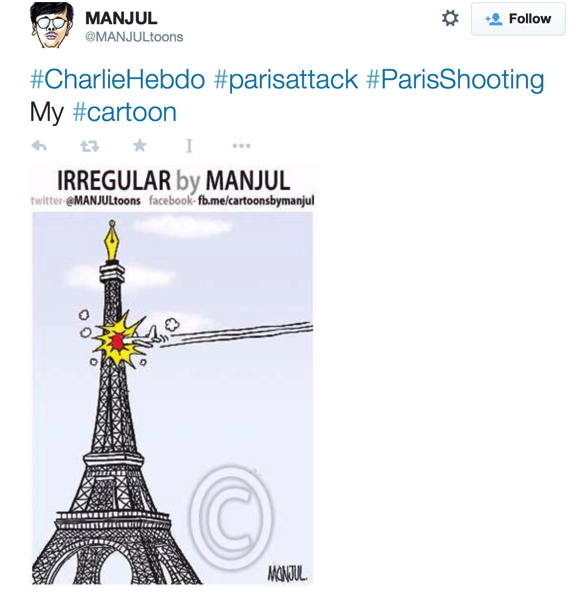

Manjul’s drawing is a variation. There is also an incredible irony in these drawing, by the way, relative to choice of targets and the financial aggression wreaked by terror. As I tweeted yesterday, so much for the amount we’ve spent on airport security.

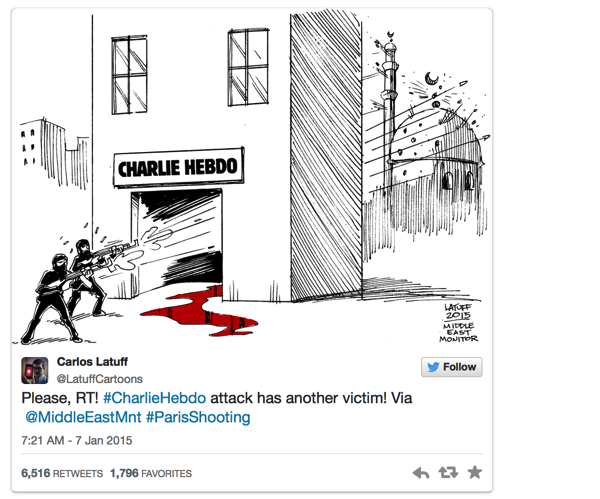

Latuff’s cartoon, in contrast, was the most politically practical. Depicting the bullets penetrating through the Charlie Hebdo office and hitting a mosque, theme here is backlash. (Let’s see what the coming days bring. The outpouring of sympathy and understanding we saw around the Western world yesterday was also the order of the day in the immediate aftermath of 9/11.) Latuff’s point is: what goes around, comes around. In a tweet, I also mentioned that, with the French elections coming up next year, the building in the background could as well be a voting booth.

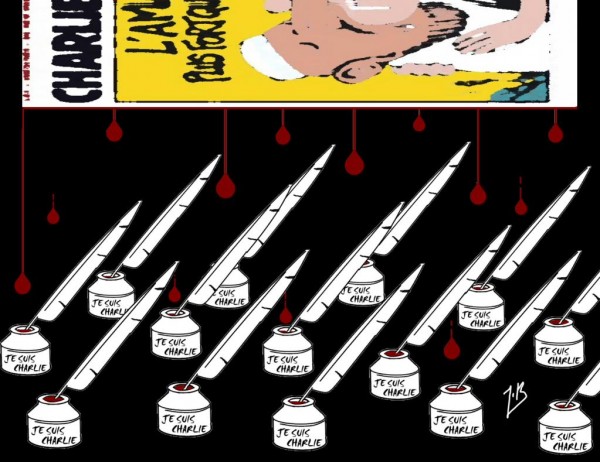

And then, we had many different cartoons like Olea’s which depicted pens and illustrator’s tools in the form of weapons. The gist, of course — as in Pope’s cartoon leading this post — is to emphasize and defend the power of the pen and the rhetoric of the cartoon as free speech. What made people such as David Campbell uneasy, however, was the concomitant violent and retaliatory quality of many of these images. (The cartoon below is by Rob Tornoe.)

In this photo just below by Eric Feferberg for AFP/Getty Images taken at a rally at the Place de la Republique in Paris, we encounter a similar tension:

On one level, we have the cartoonist under threat simply for wielding a pen (and the terrorist elevating it’s potency). At the same time, however, the cartoon creates a parity between two sets of “weapons.”

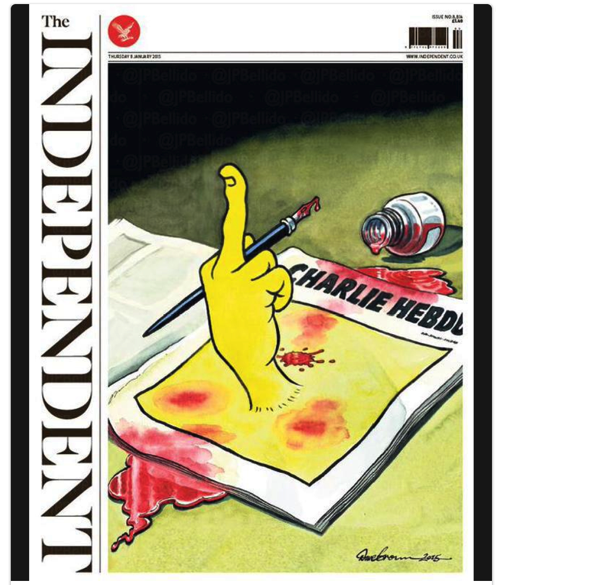

This drawing the Independent led with (I couldn’t make out the author) is a lot less ambiguous. As much as its purpose is to frame the provocative profile of the Hedbo group, the illustration just as much functions as a post-massacre fuck you.

There were other cartoons, however, that chose to draw a definitive line between terrorism and journalism, ignoring or dismissing how much Charlie Hebdo had it out for just about everybody. This text reads: “This is not a religion.” Bruland’s cartoon was not just an unqualified rejection of violence but also — and this was also a powerful theme yesterday — a strong declaration of distinction between Islam and terrorism.

Update 10:30 am PST: In thinking about this post overnight, it seems a little more needs to be said about the use of weaponry, and the depiction of aggression and violence by the satirists.

Unfortunately, I don’t believe the public relates that well to the mechanics of visual language. An opinion article by Arthur Goldhammer at Al Jazeera America and the corresponding thread on Lindsay Beyerstein’s FB page expresses and struggles with the tension a lot better than I did above. There is certainly an irony in defending the Hedbo group’s right to be as blasphemous and vicious as possible toward any person or institution, political or religious, it deemed sanctimonious when nobody ever did before. (Posts like this one at Quartz get at that point quite effectively.) They could “get away with it,” as I see it, for two reasons. For one thing, cartoon language and the language of visual parody is unique — it inherently insulates any statement with humor and the structural failsafe that, at some level, we’re just joking (even if we’re not). Second, Hedbo itself was, yes, involved in a form of asymmetrical warfare — an intellectual kind.

Their missives (as opposed to missiles, though indistinguishable in the cartoon realm here, via Z.B.) were based in the understanding that they could be that vicious because the sacred cows they were attacking were that powerful and ensconced and that institutionally or morally “bulletproof” that Hedbo’s fusillades (represented by the pen/weapons above) might expose hypocrisy but could never really hurt.

It’s not wonder Mr. Charbonnier was so pissed off at Islamist fundamentalists, among others, for failing to recognize either point one or point two. Impressively, he was willing to die over the failure to take a joke.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus