Notes

Our Take on the New Charlie Hebdo "Muhammad" Cover

If you remember, a phrase and concern that echoed through America in the shell-shocked aftermath of 9/11 was: “is irony dead?” It seemed no one could imagine humor as a conduit of meaning anymore. The wry use of words or pictures for understatement, overstatement or framing the opposite seemed off the table forever. What an epic and profoundly peculiar situation, then, that an audacious group of visual parodists and political satirists in France should not only serve as the inheritors of that attack but to also embody Ground Zero.

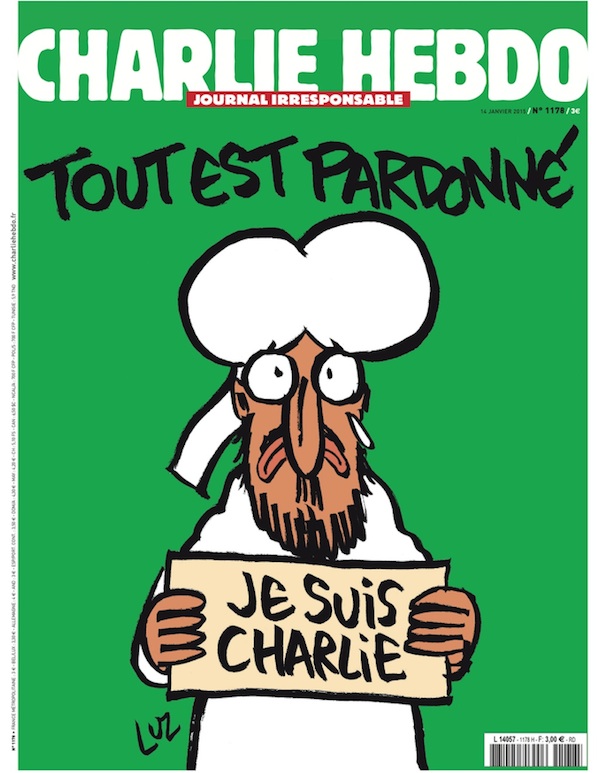

The first Charlie Hebdo post-attack cover cartoon is brilliant on two scores, one that is pretty obvious and another that is less so. If you haven’t seen it, by the way — which is possible because traditional western media, starting with the NY Times, continues to treat the cartoons at the center of this story as “the thing that cannot be seen” — the cover shows the Prophet Muhammad shedding a tear, and holding a sign saying, “Je suis Charlie” (“I am Charlie”) with “All is forgiven” printed above it.

What’s clear to anyone familiar with political cartooning, of course, is that the surface content, in the spirit of bi-direction, also means the opposite. To that extent, this cover tugs liberally on that detonation cord wrapped around the assignation that the Muslim world is not Charlie and finds everything about the publication’s parody of Islam completely unforgivable.

Still, the first piece of brilliance — and an extraordinary stroke of humanity, if you ask me — is the subject and circumstance of the drawing off of which the parody pivots. (I’m not surprised they went through “umpteen” tries, as they say, before “they got it perfect.”) The ability of the Charlie Hedbo staff to still locate a sense of humor, of irony, of parody — to return to (this form of) work just days after its long time colleagues-in-barbs were slain before their eyes and the office turned into a slaughterhouse — can only be sourced from one quality. That’s: understanding. So, to the extent the opposite meaning needs a literal foil, what Charlie Hebdo provides us — in an atmosphere crying out for understanding — is a manifest image in which Muhammad is not blasphemed at all, but makes himself visible against that peaceable green because the actions in his name are not representative of him and forgiveness (beyond just intolerance of satire) is in order.

There’s a second dimension to the drawing, however, that I’m not sure people are going to think about — and its why Muhammed, in our title, is in quotes. If the Hebdo people have publicly stated that this is Muhammad, and western media is echoing the fact without question, the cover does no such thing. Sure, the magazine is living up to its blaspheming reputation — and understandably showing blood in its eye — by unquestionably touting this figure as the prophet. Just as brilliant and understandingly, however, is that fact that this figure is as much some guy in a turban — an Islamic everyman. Considered that way — and this meaning has got to be honored too, the Charlie Hedbo staff, torn up as it is, is shrouding itself in the thinnest veil of mockery. What emerges much more strongly and most admiringly, in fact, is an identification with Muslims and the sharing of a tragedy. If the now ubiquitous sign reads “I am Charlie,” in the authorship and the parody on its face value, Charlie, in its own grief, is also saying: “We are you.”

(illustration: Rénald Luzier/Charlie Hebdo)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus