Notes

Glory as a Stage Show: On Mark Peterson’s Vegas Megachurch Photos

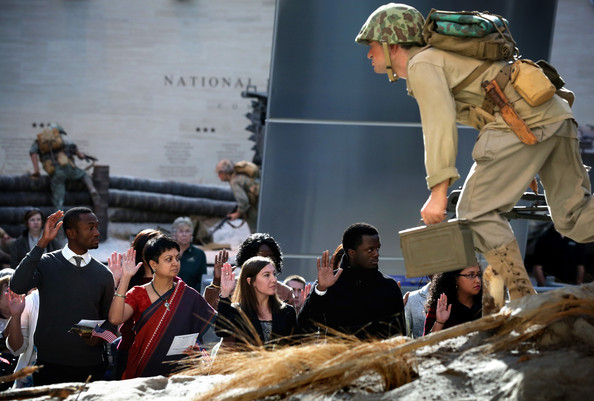

This is just one selection from Mark Peterson’s photo essay about evangelical megachurches in Las Vegas, Nevada. If you’re at all intrigued by this notion that many contemporary believers try to “be in the world but not of the world,”—which is to claim, of course, that one can inhabit and yet avoid being a product of culture—then the entire photo essay certainly is worth a look. Very much aware that Sin City megachurches are bound to put a number of cultural tensions on display, Peterson offers thirty-four photographs that capture a social and cultural aesthetic where the worship service starts to look and feel very much like a Vegas “stage show.” Peterson’s photographs supply a strained, and by turns uncomfortable, optic that emerges when the glory of heaven shines down on “the shadow of Sin City’s strip.” When it comes to church services, what happens in Vegas is a sight to behold.

So let’s admit it. The show looks pretty spectacular. This may not be your grandfather’s Sunday best, but it’s clearly in the running for Sunday’s best show. Peterson’s photograph places us right down front at a high-energy, high-tech, multi-media extravaganza where lights, camera, and action are the name of the game. Notice how the jumbotron projects a live feed from a proverbial fly-on-the-wall perspective. Thanks to foresight of the production team, those of us taking it in on the church floor are just as much a part of the show as the band members rocking out on stage. So give the casino a break but don’t miss out on any of the excitement. They’ve got live music, sure, but we have a great live band, too. And if winning at blackjack is what gives you a thrill, then you should come on down because here we can nourish your soul. Here you’re a part of something different, something set apart, something special. You may be in Vegas, but you don’t have to be of Vegas.

But looking at the photograph this way starts to feel a bit cynical, especially if un-ironic cultural appropriation is the only optic we notice. There really is more to the picture. Sure, there is spectacle to be seen here, but there is also a rich offering of symbolism. Neatly divided into three horizontal fields, it’s worth noticing how the photograph compositionally performs the classic tripartite cosmos of medieval Christianity. In the dark, upper third of the photograph, we see the kingdom of heaven, the mysterious source of light, the divine power, eternal glory, and even a god’s-eye view. In the middle third we see the stage of human drama, a frenzied cooperation where despair and devotion can look very much alike. The pastor—whose location in the visual center of the photograph attests to his role as mediator between God and the souls under his watch—down on his knees, embodies the grounding, stabilizing force of religious experience. And do we see down below, in the lower third of the image, what the ancient Greeks called hades, a realm where lost souls are drowning in separation from God?

If one reading is too cynical, the other may be unfair. What business is it of ours to look, if not voyeuristically, then at best analytically at the private religious experience of someone else? It feels positively intrusive to look over someone’s shoulder while they’re seeking an intimate moment with the divine. But how intimate is the moment we are looking at, really? Charismatic worship relies on external, bodily displays of personal faith. When the Holy Spirit moves you, the proof of that is supposed to be visible. It’s a fundamentally ocular-centric mode of demonstrating experience with the divine. And since visibility is key, so, too, is the function of the observer. What this photograph helps us understand is how channelling a personal connection with the divine sometimes works better when it’s publicly performed.

This photograph blurs ethical boundaries between voyeurism and analysis in the same way that it blurs symbolic boundaries between heaven and earth, and social boundaries between private and public. That’s a fair response given the likelihood that boundary-blurring—dare we say, inhabitation of the gray area—is precisely what happens when light and darkness converge, when the glory of heaven shines down in the shadow of Sin City. Being in the world but not of the world necessarily means embracing that tension and contradiction, and a big part of what makes Mark Peterson’s photographs so compelling is the way in which they capture the aesthetic register of that cultural tension and contradiction.

— Philip D. Perdue

(photo: Mark Peterson/Redux for MSNBC caption: Pastor Paul Goulet during services at the International Church of Las Vegas (ICLV). The congregation totals about 10,000 members.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus