Notes

How the Pictures are Killing Us: The Dynamics of the Sotloff and Foley ISIS Videos

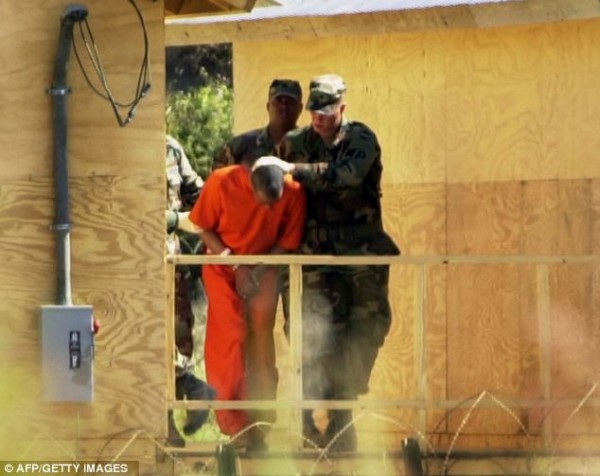

Guantanamo Bay, 2013

The PR war. The pixel war. The virtual front. The social front. The battle for thoughts and memes. The planting of minds. The ambient space. War jamming.

Back in November 2012, in response to that winter’s Gaza – Hamas hostilities, many of us were taken with a whole new dimension to war. In parallel with the “actual” physical fighting, what was noteworthy was the fury and the arresting impact of the propaganda, the back and forth in slogans, parried facts and, specifically, horrid propaganda images on Twitter. Because this, in its intensity and breadth, seemed new and different, I wrote:

As of this week, the visual data is no longer distant, it’s no longer delayed, and in its initial views, it is barely filtered, even if coming from the NYT or the BBC.

Without the temporal and editorial mitigation that has emotionally and intellectually abstracted visual news, welcome to a media space in which we are consuming hostility and processing raw data and raw propaganda almost as quickly as the war correspondent, the fighter pilot, the governments, the diplomats and the antagonists themselves. With the rapid evolution of Twitter and Instagram, and the now-essential nature of these services (as Steven Mayes explains in a new interview with Pete Brook at Wired…), the imagery has literally become experiential.

How matter-of-fact those words seem now. At the same time, however, I don’t believe that we as a culture, or a news consuming public, or as a media, or a government have progressed very far in appreciating the new set of terms. And, with the release of the two recent ISIS beheading videos, I believe we’re not only suffering a difficulty in understanding but we’re being badly manipulated as a result.

Two years later, I think we can clearly see that, between pixels on our screen, photos in a newspaper or the real splatter of blood, the imagery has indeed become experiential — that there is hardly a distinction anymore between physical and virtual war. Dynamically though, what is it we’re missing? If the Foley and Sotloff videos felt like a piercing blow, if just from the bloodless screen shots, what is it that so pierced us? In ambient space, it’s not about physical damage as much as emotional damage. What states and organizations largely battle over today is emotional turf, the assets at stake being identity and dignity, the attribute most at risk being self esteem. The visual can represent physical war (troops rolling into a foreign city), a symbolic act (burning down a building) or something performative (a beheading). Regardless, the result (“the net effect,” if you will) is “perceptual injury.”

Take the Ukrainian soldier on the tank in the newswire photo above, for example. What informs a photo like this, a Ukrainian soldier battling Russian separatists in such a phallic pose? With the visual media as the conduit for PR war and the battle for ego supremacy, this image is as much a poke at Putin, shown enough times with his shirt off in his perpetual attempt to tie his own masculinity to the Russian state.

When it comes to the treatment of the Foley and the Sotloff videos, certainly there are issues and decisions to be made about what and how much to show. What that calculus fundamentally overlooks, however, is the dynamic surrounding their consumption and how we process that stimuli. The mere suggestion of placing the imagery in any context, however — to discuss how to think about it, and God forbid, how we might examine it — must seem to most like heresy. And yet, devoid of context, we remain shockingly vulnerable and largely ignorant to how such imagery can provoke us. That being the case, no wonder the instinct is to simply ban the imagery, erase it — to just make it go away. The instinct to completely censor provocative events on the digital front, however, is a slippery slope indeed.

We respect Steven Sotloff and won’t air images of his death, or him in a jumpsuit. We suggest all media do the same. #ISISmediaBlackout

— Al Jazeera PR (@AlJazeera) September 2, 2014

So the western arm of Al Jazeera would black out the event so its audience would have no picture of it at all. Doesn’t that invest the digital strike and the emotional warfare, however, with that much more power? At the same time, the black hole would cause the network’s audience to necessarily lose any sense of how and why this visceral ordnance might have such resonance, let alone inform decisions or reactions on the part of the administration or the Pentagon. When you start blacking out reality, as opposed to countering it with more context and understanding, where does that end?

Perhaps what’s most telling about this Al Jazeera tweet, by the way, is less the threat of blacking out the event then it is the reference to the jumpsuit. Isn’t the isolation of this garment, and our recognition of it, a start toward countering the force of the blow? As opposed to media resorting to denial, It seems far more powerful and more “disarming” (in both a rational and militaristic sense) to inform us why these elements effect us so – starting with how the orange jumpsuit, for example, is such a signifier and manipulative attempt to create an equivalence between this beheading and America’s terror war. This Barbara Ehrenreich quote from her Facebook page strikes me in a similar way as the Al Jazeera tweet. She writes:

America’s courageous response to ISIS: We’re being urged not to watch the latest beheading on Youtube, so they won’t get the clicks. Yes, that’s our most up-to-date weapon against terrorism — click deprivation.

So pictures in the social sphere have now acquired so much capacity to injure that “knowledge is power” has been replaced by the weaponizing of denial? (The decision to boycott the beheading videos or not propagate links to them, by the way, goes far beyond just depriving ISIS of web traffic.) The statement also assumes that the distribution of images and the consumption of images is automatic, neglecting that we can apply our intellect, and not just our will to that. One subject thread on Twitter in the aftermath of America’s shock over the beheadings emphasized the point that beheading, especially as conducted by certain Middle East allies, happens regularly.

The ISIS beheadings are atrocious, yes. But the 20+ beheadings our allies Saudi Arabia have carried out since 4th of August? #1ruleforsome — Tom Brennan (@TheBrossiah_BoK) September 3, 2014

Of course, most of those tweets were motivated by moral pushback and the frustration that to America and its media, life is somehow more precious in the West than it is in the Islamic world. For purposes here, however, it’s more instructive to look at these tweets – and in some cases, the gruesome images accompanying them – as informational data along the lines of the orange jumpsuits. While trying (not to ignore the horror or sublimate the shock, but) to regain equilibrium from the Foley and Sotloff videos, it’s actually helpful to know that the Saudis are chopping off heads on a regular basis. That’s not just macabre, that’s news and factual knowledge every political and media consumer can use to help process these toxic images. Specifically, the most important “anti-weapon system” we have in the emotionally lethal battle space is context.

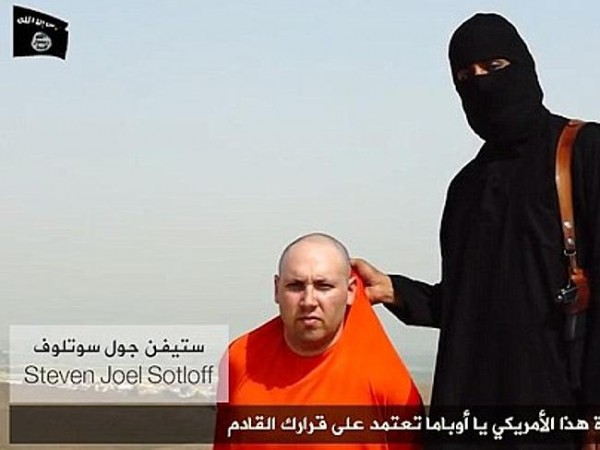

Which brings me to the ISIS screenshots of Steven Sotloff. (Dare I publish them and invite the symptoms they elicit, that’s the whole point.) But then, which is the screenshot from the August 19th video and which is the one from September 2nd? What is the difference, if any, and is it obvious which is the one he died in? Again, you might find these questions blasphemous. At the same time, however, and with the utmost respect to Mr. Sotloff and his family, he isn’t the first man to die in a war. And, doesn’t ISIS win when, in the face of the imagery, we simply abdicate the opportunity to even consider the what, who, where and when?

Freud talked about working through trauma and emotional blows in terms of “decathecting.” The term refers to a process of peeling off the emotional charge to arrive at a place of greater awareness, depth and understanding. It’s that concept, as difficult and fraught as it is, that allows us to contain, and ultimately disarm the weapon rather than have it (continue to) maim us. (..If that idea, again, sends a chill up your spine or a revolting sensation through your gut, that’s the shrapnel talking.) Without desensitizing ourselves, it is essential we be able to access these images without taboo. Because of the sensitivity, I will not belabor the two scenes above. What I will say, however, is that it makes a fundamental difference if, and how we perceive those two scenes of Sotloff — one from the Foley execution video and the other from Sotloff’s own. It’s the difference between shrinking in horror or drowning in revulsion as opposed to considering how long it took for Sotloff’s hair to grow out, or examining the videos to assess how the backgrounds and the weather compare, and to assess where the video cuts and the edits are to even know and if it’s real or not. Of course, much of this analysis is the providence of experts. But, it’s with that awareness that we start to decathect the terror and unwind the formula of our manipulation.

The killing of these two men is terribly disturbing, and to me — if you follow this site at all — the killing of journalists and visual journalists is especially unconscionable. But when war is fought as much socially and experientially through visual gestures, rhetoric and symbols, the fastest way to lose the battle — to enemies with otherwise radically fewer material assets — is to cede emotional ground when bombarded with scenes designed so much for effect. What Bin Laden understood and the social media masterminds behind ISIS have further refined is the visual secret, in one shot, for making themselves all powerful and for bringing America to its knees. It’s the ego blow.

(photo 1: Evgeniy Maloletka/AP. caption: A Ukrainian soldier sits atop a self-propelled gun as an army column of military vehicles prepares to roll to a frontline near Illovaisk, Donetsk region, eastern Ukraine, on August 14, 2014. photo 2: Getty Images 2013 via dailymail.co.uk. screenshot 3 and 4: August 19th and September 2nd, 2004. ISIS video.)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus