Notes

Drone Visuals, Selfies and Human Agency

“By definition, a government has no conscience. Sometimes it has a policy, but nothing more.”

— Albert Camus.

Photographer Tomas Van Houtryve puts the above quote top and center of his most recent artist statement. He believes that human activity becomes increasingly absurd and dangerous when it looses empathy.

Researching my latest WIRED piece, Here’s What Drone Attacks in America Would Look Like, about Van Houtryve’s Blue Sky Days, I was shocked by the number of civilians killed by U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen and Somalia.

“The Obama administration doesn’t release a lot of details, so firm figures are hard to come by. But the Bureau of Investigative Journalism estimates unmanned aerial vehicles have killed between 2,296 and 3,718 people, as many as 957 of them civilians,” I wrote.

President Obama’s Drone War is not widely discussed. Drones operate remotely and forge the very distance that prevents a critical look at their continued use. Drones dismantle empathy.

If a technology with extremely powerful spying and killing capabilities is shielded from public scrutiny, there is bound to be abuse,” says Van Houtryve.

WHAT’S IN OUR WORLD?

Art can foster empathy. At least, that’s an aim of political art, no? There are many worthy projects that have co-opted and subverted drone visuals:

Jamie Bridle outlines drone shadows in the streets and conceived Dronestagram to offer social media views of drone strike sites from satellites.

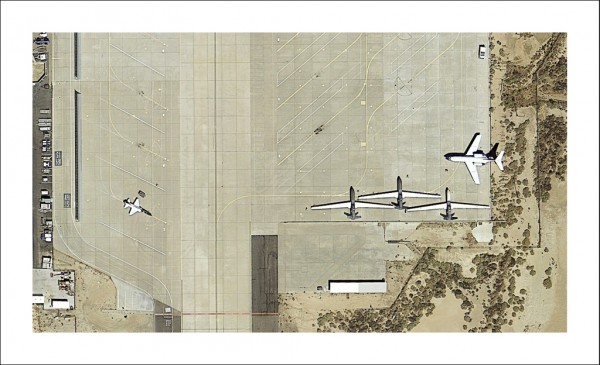

John Vigg surveilled drone research labs and airports.

Trevor Paglen photographed drones from afar.

Josh Begley’s App, MetaData, updates users on drone attack.

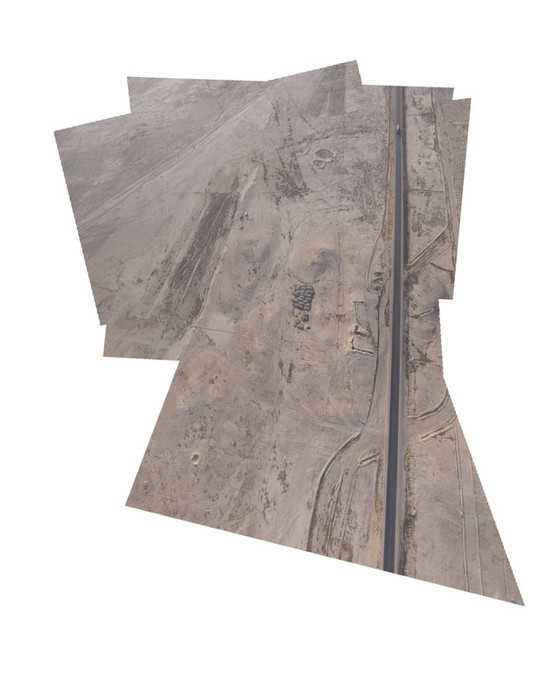

Raphaella Dallaporte used a drone to do archaeological surveying in Afghanistan.

And just in the past few weeks, an Inside Out project named Not A Bug Splat, inspired by JR, plays up the consciences of drone “pilots” by unfurling enormous images of children in strike zones. However, the novelty of these projects (still) suggests we are not up-to-speed on drone operations.

WHAT’S IN A WORD?

Furthermore, I worry about how the definition of the word “drone” is shifting. When we hear “drone,” do we think about military-grade killer robots or about newer domestic-use quadcopters like the one at the top of this post?

The photo and video world has embraced smaller, non-lethal drones — we oohed and aahed at this aerial surf video and we protested when the police forced down a drone flown over a traffic accident by an off-duty photojournalist.

Soon, a small drone will be a part of every photographers kit.

Also, new legislation is being written to catch up with the technology and the proliferation of public drone ownership and operation. The FAA had self-appointed itself as the authority on drone use and looked disapprovingly at Joe Public sending lil’ aircraft up in the air. So, the FAA started sending out cease and desist letters and $10,000 fine threats.

The recipients — commercial photographers — weren’t threatening homeland security; they were mostly using camera-mounted drones to map agriculture, oil fields and the like. One commercial drone user, Raphael Pirker, challenged his fine in court. He won and nullified the FAA’s authority over him or any other drone operator.

“Pirker’s attorney maintained that the FAA could not simply declare a regulation without having a public notice-and-comment period. His argument went like this: Congress has delegated to its bureaucracy the authority to make rules, but when new regulations have a substantial impact on the general public, the government must have hearings and take comments,” wrote David Kravets for WIRED.

Until those hearings, it is a free-for-all. We must just hope that creepy idiots who want to spy through windows are the exception.

There’s a third player in the mix though. Between the everyday citizen and the military industrial complex are corporations. Who would bet against Amazon actually delivering your slippers by drone? Or Facebook delivering WiFi via drones to the entire globe in the next decade?

Overall, we hope that citizens retain access to the use of drones just as corporations and the state do. We hope citizens’ drone use is protected by laws similar to those allowing street photography on public thoroughfares.

NEW WORDS IN OUR WORLD

‘Drone’ is a new word in photography. ‘Selfie’ is a new word in photography too. In fact, the emergence of the two words was almost parallel.

The earliest usage of the word selfie can be traced to an ABC Online Australian internet forum, on 13 September 2002. Just seven weeks later, on November 3rd 2002, the first ever lethal U.S. drone strike hit Yemen, killing six.

At the turn of the millennium neither the words drone or selfie, as we know understand them, were in our lexicon. I’d argue the definition of both terms is ongoing apace, but for different reasons. Drone visuals and facts are obscured; we must search them out. Selfie visuals, on the other hand, are impossible to avoid.

At some level, the selfie provides the everyday citizen a type of agency and incorporates our foibles, connectedness, and our awkward relationships with social media. Selfies may not be inherently humanizing but they are individually created and do reflect human idiosyncrasy.

By comparison, drone scopes reduce humans to video-mediated targets. Drone visuals eradicate individuality and of course, very literally snuff out human life. The selfie, spoken of at least, is a completely controllable form, whereas the drone is an apparatus of control. It’s bottom-up liberation vs. top-down oppression.

That these are two of the main new words we are processing together as a culture is intriguing to me. If the near-simultaneous emergence and widespread use of the words “drone” and “selfie” seem relevant to our remotely-networked globe, their contrasting correlations to determination and guidance seem only more so.

Fodder for further investigation, the drone and the selfie inhabit different ends of an image spectrum. Both in terms of production and consumption, the selfie is all us and the drone is all them. We know us well. We don’t know them at all.

— Pete Brook

(adapted from PrisonPhotography.org)

Note: the Van Houtryve photos are a major feature in this month’s Harper’s magazine. Available online to subscribers or on the newsstand now.

(photo 1: Don McCullough via Flickr. photo 2: James Bridle. caption: Drone Shadow 002 (2012) by . Istanbul, Turkey. photo 3: James Bridle/Dronestagram – Instagram. photo 4: John Vigg/Where’sVigg.com via satellite imagery. photo 5:

Trevor Paglen/Altman Siegel. caption: Untitled (Predators; Indian Springs, NV), 2010. photo 6: JoshBegley.com. photo 7: Raphael Dallaporta/Institute photo 8: NotABugSplat.com)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus