Notes

Even if the Police Report Wasn’t Buried by the Holiday, What Photo Would Make Us Understand Sandy Hook?

Last March, Michael Moore pleaded for Americans to demand the release of photos from the Sandy Hook Elementary shooting.

“If we were to seriously look at the 20 slaughtered children – I mean really look at them, with their bodies blown apart, many of them so unrecognizable the only way their parents could identify them was by the clothes they were wearing, what would be our excuse not to act?” he asked.

“How on earth could anyone not spring into action the very next moment after seeing the bullet-riddled bodies of these little boys and girls?”

Moore points to critical moments when gruesome photojournalism — the murder of Emmett Till, the My Lai massacre in Vietnam — made a tangible dent upon the national dialogue, citing the impact that pictorial consequences of violence can have upon a nation’s psyche. But today, unlike the 1950s and 60s, we seek to insulate ourselves from an (often uninvited) deluge of visual obscenity, detaching from the deeper implications of these images.

“As of right now, we’ve somehow all decided together that we don’t need to look, that in some way we’re okay with what’s in those pictures — just as long as we don’t have to look at the pictures ourselves,” he wrote.

We need an image from Sandy Hook so painfully gripping that it calibrates our understanding of what occurred with tangible action towards a better future. And then Moore’s moment of truth arrived. Sort of.

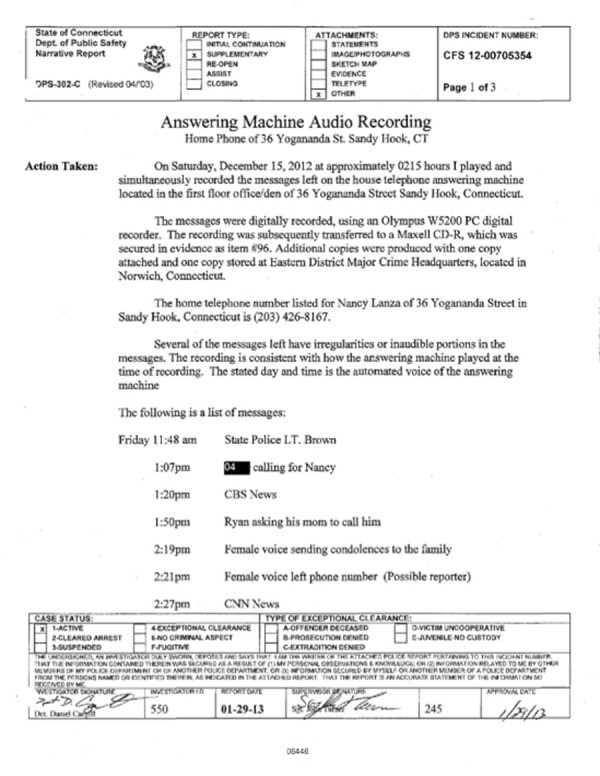

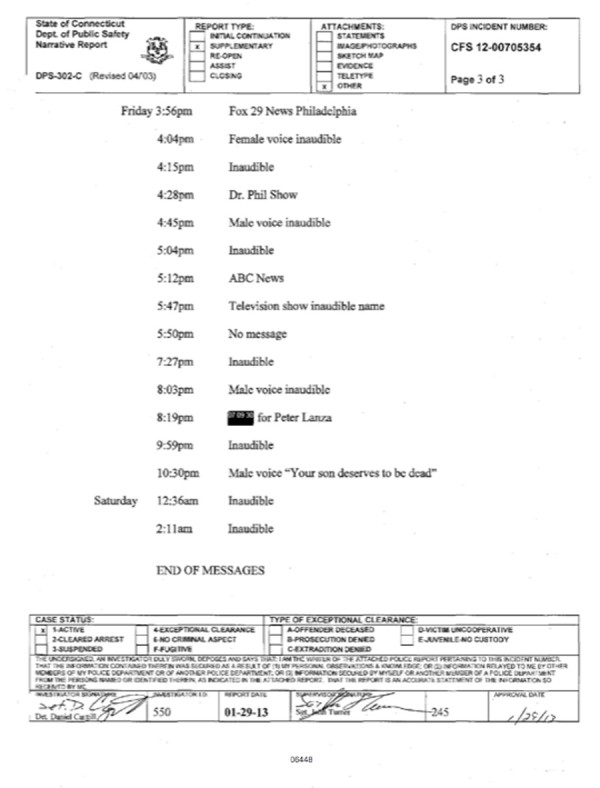

On the Friday before last, the Connecticut State Police released a report detailing the findings of an intensive, yearlong investigation. In a letter heading the release, Reuben Bradford, CT’s Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection commissioner, penned the rationale for publishing the heavily-redacted evidence package, which includes photographs, witness statements, audio of the robo-calls to parents, logs of Nancy Lanza’s answering machine and dash-cam videos of police rushing to the scene.

He writes:

“Throughout this report, the names and contextually identifying information of involved children have been withheld. This contextual information includes descriptions or images of children, their clothing and their belongings and references to their family members as examples.

…

Consistent with certain permissive exemptions of the Freedom of information Act and the constitutional rights of crime victims we have chosen to withhold that information.

…

All visual images depicting the deceased have been withheld, as well as written descriptions whose disclosure would be highly offensive to a reasonable person and would violate the constitutional rights of the families.

…

I hope that the release of this report, though painful, will allow those who have been affected by it to continue in their personal process of healing, and will provide helpful information that can be put to use to prevent such tragedies in the future.”

These new images didn’t see major play in the mainstream media, although the major wires made many available to their subscribers. One can offer guesses: were editors, many having spent the past weeks compiling look-backs on 2013, feeling fatigued at the incessant reminders of violence past? Was it a question of timing? The report, hundreds of pages long, was released two days after Christmas, on the Friday before New Years.

But do these photos even merit the public’s eye? They aren’t the victim photos Moore was pleading for, nor are they seemingly even that remarkable. They’re divided into two categories: crime scene and evidence.

The crime scene photographs chronicle the mundane trappings of normalcy; they are the epitome of standard in both content and form. And in that sense, they’re almost too routine to matter.

It’s only after we peer into the contents of Nancy Lanza’s underwear drawer — just inches from the bed where she was murdered in her sleep — we begin to feel the guilt of the unintentional voyeur.

No explanation needed here: the splatter marks up and down Adam Lanza’s tactical cargo pants speak for themselves. We could spend days wringing meaning from the details that strike us here. Inevitably some will; I imagine Sandy Hook conspiracists have been foaming at the mouth.

Does it really matter that there’s a stuffed animal atop the Lanza’s gun case?

That Adam, a vegan, ate a meal in front of his computer from one bowl with a fork and another bowl with a spoon?

That the words “hopes and dreams” appear in a photo of the date scribbled on a classroom’s whiteboard, as if the documenting officer decided to share in tribute the poetic irony he noticed?

One of the many qualities of a photograph is that it often feels conclusive. And indeed, these images will support answers the public has already arrived at.

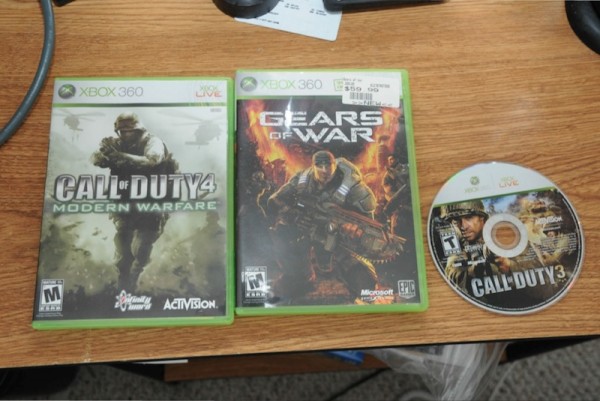

We’ll point to Lanza’s copy of Call of Duty and blame his actions on his conditioning and desensitization to violence.

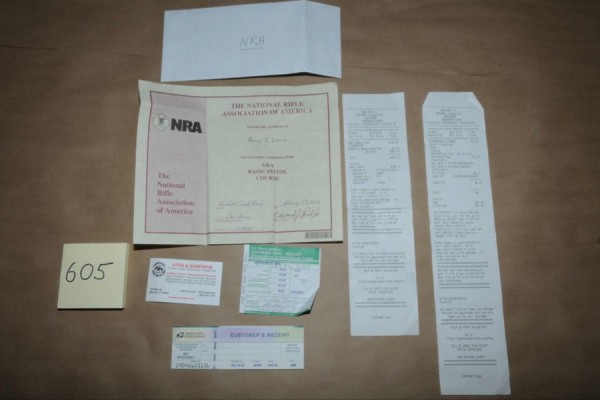

We’ll point to his mother’s NRA training certification and blame her for introducing guns into her son’s life.

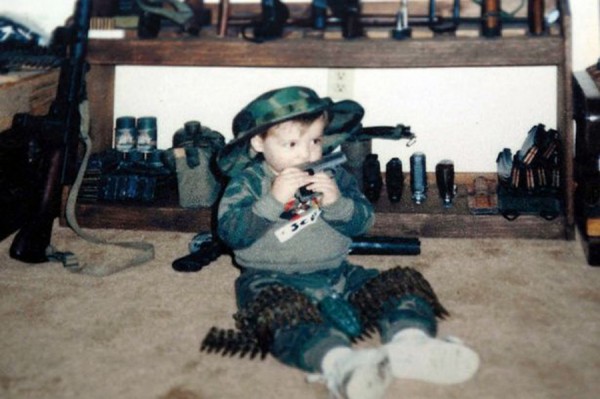

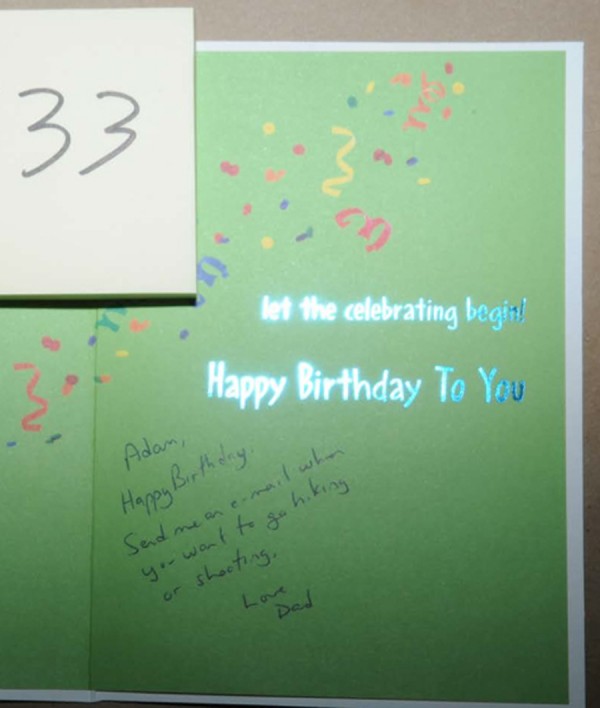

Or his father’s tragically ironic birthday card as reinforcing the same — reflected also in the photo purporting to be Lanza leading this post.

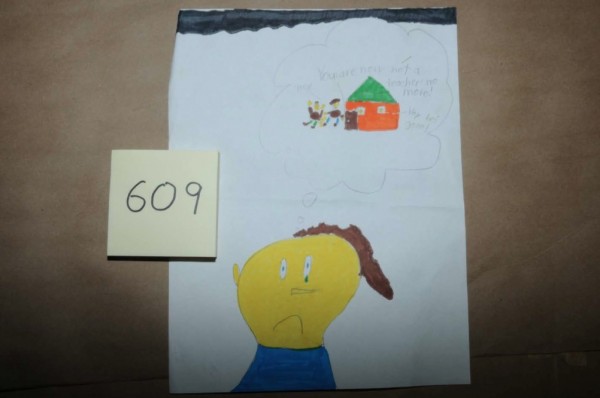

We’ll point to his absurd childhood drawings as missed warning signs.

So do the other types of images released — the evidence photos — offer something more accurate? Last December, John Lucaites noted the conundrum of the modern mass shooting: that whether we choose to gaze in horror or look away, we inevitably fail to act.

“The photograph that is missing from the archive of images of this tragedy is the photograph of the automatic weapons that were used to extinguish twenty six innocent lives,” he wrote. “Until we see that photograph, and I mean really see it as the material cause for what is happening, we will be caught perpetually in the embrace of looking in horror without speaking or looking away.”

For better or for worse, we aren’t seeing photos of dead children. As valid an argument as anyone makes, can graphic images of murdered children, like we recently saw from the Syrian government’s chemical weapon attack in Ghouta, really make someone care?

Well, here it is — the precise trigger that was pulled to extinguish the lives of first-graders.

Feel any different?

— Anonymous

(photos:Connecticut State Police)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus