Notes

James Whitlow Delano – Fourth Dispatch: My Odyssey to Learn What Gold Wreaked on Suriname

In this longread and photojournal for BagNews Originals, photographer James Whitlow Delano chronicles his investigations in Suriname. In previous posts in the series, he details the devastation of the rainforest in Malaysia and Indonesia and the impact on indigenous tribes resulting largely from the corporate cultivation of palm oil. In Suriname, the influx of foreigners, the ecological toxification and the adverse cultural effects are largely the result of intensive mining spurred by international conglomerates.

Although it looks natural, this canal originally excavated by African slaves, that cuts from the Commewijne River to the Atlantic at Matapica, has been completely reclaimed by the surrounding mangrove forest. Canal excavation led to more slave escapes than other forced labor, leading to the creation of bands of free Africans who later formed various Maroon ethnic groups. Commewijne, Suriname.

Although it looks natural, this canal originally excavated by African slaves, that cuts from the Commewijne River to the Atlantic at Matapica, has been completely reclaimed by the surrounding mangrove forest. Canal excavation led to more slave escapes than other forced labor, leading to the creation of bands of free Africans who later formed various Maroon ethnic groups. Commewijne, Suriname.

I never intended to go to Suriname. This Afro-Caribbean, Cambodia-sized country of a 1/2 million people is almost completely eclipsed by its much larger Latin neighbors, Brazil and Venezuela but, entirely by chance, the Dutch photo organization, Noorderlicht sent me there. After the utter environmental devastation I have recorded in equatorial Asia, it almost came as a shock to find rainforest that was actually taking back land once cleared by humans.

Harvey Lisse, my Surinamese friend and colleague, wanted to show me that, in Suriname, things were not always how they appeared to be. Just a half hour into our journey outside the capital, Paramaribo, the great Amazonian rainforest began. It was that intact because large-scale industrial logging had not yet arrived. The highway was arrow straight as we sped past the massive, orange-dusty Suralcoa Paranam bauxite processing plant. Soon we hung right before reaching the Afobaka hydroelectric dam which meant we were already in Saamaka Maroon territory. In the 17th century, Africans who had fled into the rain forest to escape slavery so effectively fought off their masters that the Dutch were forced to sign a treaty ceding autonomy in this territory to the Saamaka.

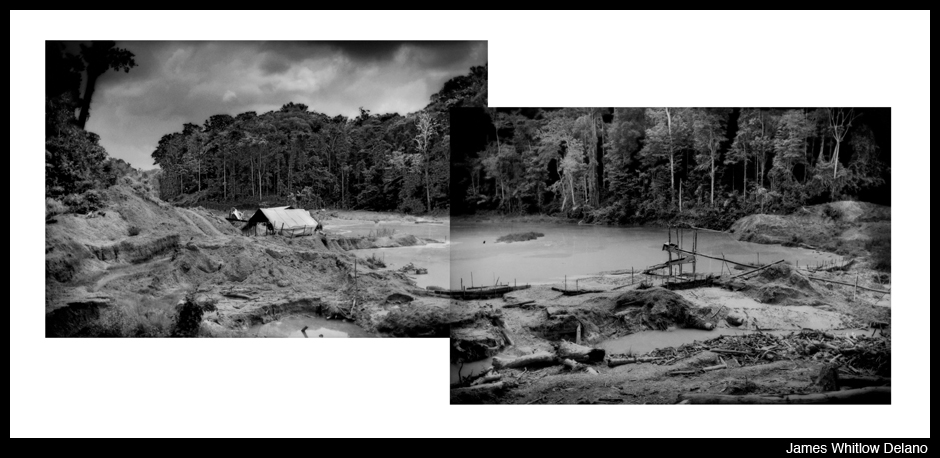

The driver turned onto a well-maintained gravel road, one which also led to the Rosebel Gold Mine run by Canadian giant, IAMGOLD. Before we reached the mine, we caught flashes of barren, poisoned watersheds through the trees until finally the road crossed what had been a river valley. Abandoned mounds of soil and dead pole-sized trees extended into the distance on both sides. In recent decades, Suriname has not escaped the proliferation of artisanal gold mining that has proliferated in Amazonia.

Large site for artisanal gold mining by independent Saamaka Maroon men near the fringes of the huge Rosabel Mine run by Iamgold, a Canadian gold mining corporation on Saramaka land. Near Brownsweg, Suriname.

Large site for artisanal gold mining by independent Saamaka Maroon men near the fringes of the huge Rosabel Mine run by Iamgold, a Canadian gold mining corporation on Saramaka land. Near Brownsweg, Suriname.

Stopping the van, I jumped out to begin photographing but Harvey advised me to be more cautious. Harvey is Creole, African-Surinamese. His ancestors were slaves until it was abolished in the middle of the 19th century. He was not Maroon, which meant, although he was African-Surinamese, he was an outsider to be regarded with slightly less distrust than me, a European-blooded foreigner.

Unlike most of the country that is blessed with a comfortable equatorial climate, fed by cool breezes, it was stiflingly hot and bright. Slowly we made our way, photographing in the treeless space using mounds for cover. He had hinted at the presence of firearms used to protect claims, so I heeded his warning. Coming up over the lip of a particularly large mound, poles had been purposely speared into the ground but it was obvious that the flooded pits had been abandoned. So we returned to the van and moved on to a Maroon village inhabited by the Saamaka. They had been relocated there in the 60’s upon the creation of the Afobaka Dam. Almost half of Saamaka Maroon territory was flooded in the name of generating power for the Rosebel Mine and the Suralcoa aluminum plant.

It was a tough, unsmiling town which opened onto a greater expanse of artisanal gold mines. We were on edge entering the gold field. Four or five young Saamaka men glared at us as we made our way past them. I quickly made a couple of photographs at a high shutter speed in the likely event that we were chased off. At least I would not return empty handed. To the left, miners had set up a makeshift camp with tarpaulins secured to posts to cut out the sun and create shelter from rain. In the shade underneath, men (who did not respond to our greetings) were stretched out on hammocks strung between poles.

Wary gazes from Saamaka Maroon artisanal gold miners as they leave their mining compound.

Wary gazes from Saamaka Maroon artisanal gold miners as they leave their mining compound.

Harvey addressed them in Sranan Tango (Suriname Tongue). After an uncomfortable silence one large man sat up in one of the hammocks and responded in a low, authoritative voice, which we took to indicate he was the crew boss. After convincing him that this foreigner was not a gold prospector coming to steal the land out from under them, he granted us access.

Harvey and I climbed up to the top the highest mound and took it all in. The freelance gold mines stretched out of sight, mostly following the contaminated watershed.

Gold miners, mostly Saamaka Maroons, excavate the Rosebel gold mine on Saamaka territory in the Amazon rainforest with high pressure hoses and use mercury to process the ore, causing great ecological damage. Near Brownsweg, Suriname.

Gold miners, mostly Saamaka Maroons, excavate the Rosebel gold mine on Saamaka territory in the Amazon rainforest with high pressure hoses and use mercury to process the ore, causing great ecological damage. Near Brownsweg, Suriname.

Dozens of stagnant pools fouled with highly-toxic mercury extended at intervals throughout the treeless, dead zone. We photographed as quickly and carefully as we could, knowing full well that another self-appointed crew “boss” might shut us down at any time. Four or five men, coated in mud and water, had been working below us blasting soil away from the walls of a pit when their water pump broke down. Now, oblivious to our presence, they were discussing how to get the pump up and running again while one man went off to get something.

Handmade sluice boxes, used to separate gold from the soil and river stones, had been erected willy-nilly. Most of them sat idle but a couple of them dripped a slow stream of brown water. The miners destroyed an entire watershed to extract a little gold. Mercury, or quicksilver, is used to increase the recovery of gold, but certainly these miners were fishing for table scraps compared with the quantity of gold being extracted nearby by IAMGOLD at the Rosebel Mine. That mercury also leaches into Suriname’s complex of rivers. Entering the food chain, it can result in mercury poisoning which attacks the nervous system causing muscular control, numbness and even paralysis. As I prepared to leave Suriname, I wondered which was worse: a logged-over rainforest replaced with oil palm like in Malaysia or a relatively intact rainforest containing poisonous rivers?

Saamaka Maroon man takes a drink on a hot day near handmade sluice box used to separate gold from the soil and foul water cuts into the soft earth. Saamaka Maroon artisanal miners works independently adjacent to the Canadian-run Rosebel mine Near Brownsweg, Suriname.

Saamaka Maroon man takes a drink on a hot day near handmade sluice box used to separate gold from the soil and foul water cuts into the soft earth. Saamaka Maroon artisanal miners works independently adjacent to the Canadian-run Rosebel mine Near Brownsweg, Suriname.

Piranhas for sale in the Maroon market in Suriname’s capital city, Paramaribo. River fish are one way that mercury (quicksilver), used by artisanal gold miners to obtain higher yields of gold, enters rivers in mine run-off and then finds its way into the food chain.

Piranhas for sale in the Maroon market in Suriname’s capital city, Paramaribo. River fish are one way that mercury (quicksilver), used by artisanal gold miners to obtain higher yields of gold, enters rivers in mine run-off and then finds its way into the food chain.

Six months later, funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, I returned to Suriname. Following a tip by a Chinese-Surinamese attorney, I hatched a plan to fly into the trackless interior to access the tiny boomtown of Bensdorp. There, I was told, we could find Chinese nationals from Fujian Province mining for gold with Brasilian “garimpeiros,” or wildcat gold miners.

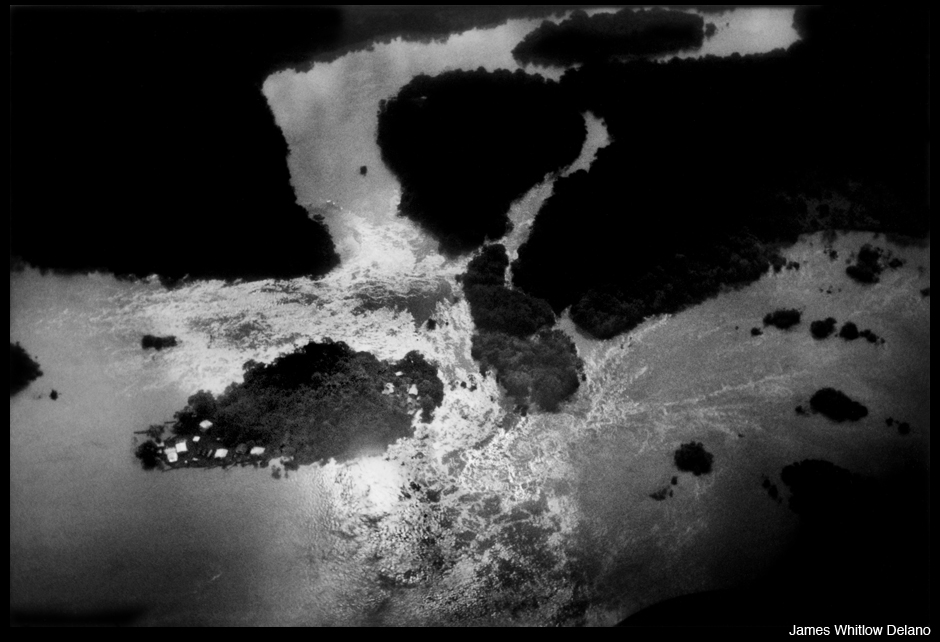

The 16-seat Twin Otter aircraft climbed into the clouds above Paramaribo and soon there was nothing below but rainforest, more of it than I had ever seen before. Flying over Borneo, it is impossible to turn your head and escape the sight of logging roads or oil palm plantations. In Suriname, the forest stretched in all directions drained by massive rivers of the kind only Amazonia can spawn; muscular, unnavigable, swiftly dividing and subdividing. Kilometers wide with a half dozen sinuous strands, the rivers feed treacherous rapids then rejoin in stretches of calm. Sometimes, though, snow-white blotches like strings of toxic beads traced the watercourses where the artisanal gold miners had done their handiwork.

Inland travel in Suriname is difficult and dangerous. Cutting through dense Amazonian jungle, wide rivers cut through dense Amazonian jungle, unnavigable by large boats because of treacherous rapids. These on the Marowijne River separate Suriname from French Guiana.

Inland travel in Suriname is difficult and dangerous. Cutting through dense Amazonian jungle, wide rivers cut through dense Amazonian jungle, unnavigable by large boats because of treacherous rapids. These on the Marowijne River separate Suriname from French Guiana.

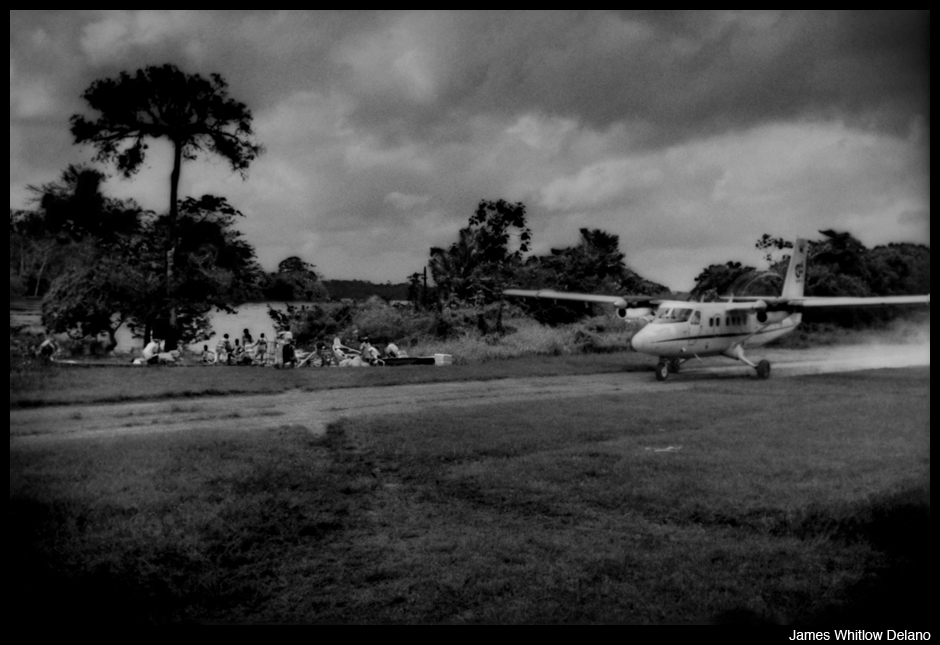

Our plane touched down on a dusty airstrip on an island in the Marowijne River you can see above. It was guarded by formidable, but friendly Europeans I took to be French Special Forces. We had been warned that lawless Bensdorp was expensive but still it came as a shock when a Ndyuka Maroon boatman demanded over US$ 25 for the 150 m, one minute, ride to shore. I managed to get him down to about US$20.

The twice daily flight to Bensdorp prepares to take off on the dirt runway while local Maroon people, either Ndyuka, Alukuu or Boni load cargo from the capital into longboats.

The twice daily flight to Bensdorp prepares to take off on the dirt runway while local Maroon people, either Ndyuka, Alukuu or Boni load cargo from the capital into longboats.

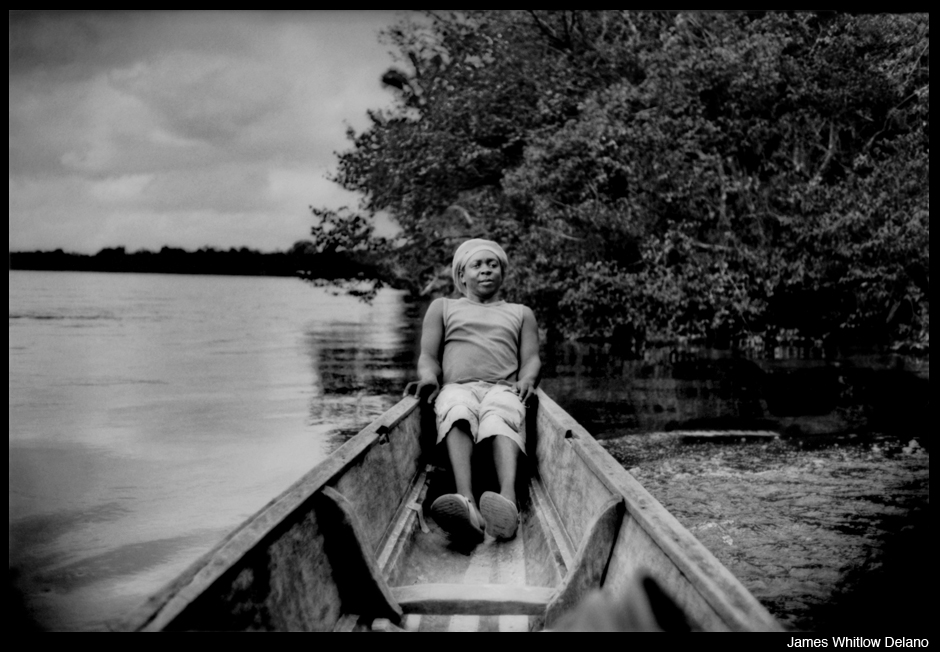

Ddyuka Maroon man in the prow of a “korjalen” that ferries passengers from the island where Bensdorp’s dirt airstrip sits to the gold boomtown. Marowijne River, Suriname.

Ddyuka Maroon man in the prow of a “korjalen” that ferries passengers from the island where Bensdorp’s dirt airstrip sits to the gold boomtown. Marowijne River, Suriname.

In Bensdorp, the preferred currency is pure gold, carried in little pouches hidden in miners’ clothes. Euros are the favored hard currency because across the river it’s actually part of the Euro zone. US dollars are also accepted, then grudgingly, merchants will also accept the humble Suriname dollar.

Nearly pure gold mined by Brazilians around Bensdorp, deep in the interior of Suriname. This crude gold is the preferred currency of interior gold boomtowns. Suriname.

Nearly pure gold mined by Brazilians around Bensdorp, deep in the interior of Suriname. This crude gold is the preferred currency of interior gold boomtowns. Suriname.

Harvey and I were led through a congregation of Ndyuka Maroons who stared back silent and poker faced. They are the masters of the river, on which all controlling supplies are transported up from the coast. We were met by a Creole man who led all of us up through the main street of clapboard Fujian-Chinese shops and Brazilian-run restaurants/pool halls/karaoke bars to our dank, earthen floor shack of a hotel. There was no running water, no electricity. Just a detached outhouse, all for the princely sum of US$ 20/night.

Maroon man, either Ndyuka or Boni, walks up the empty main street of the gold boom town of Bensdorp all but taken over by Brazilian Garimpeiros and Chinese merchants from Fujian Province. Former escaped slaves fled deep into the Amazonian forest to places like Bensdorp to escape their Dutch masters and build new free African societies. Suriname.

Maroon man, either Ndyuka or Boni, walks up the empty main street of the gold boom town of Bensdorp all but taken over by Brazilian Garimpeiros and Chinese merchants from Fujian Province. Former escaped slaves fled deep into the Amazonian forest to places like Bensdorp to escape their Dutch masters and build new free African societies. Suriname.

“We’re going to need to hire an ATV (all terrain vehicle) to take us to the gold mines and the next town over,” I told the Creole “hotel” owner. “How much is that going to cost?”

“You can hire one for 2 1/2 grams of gold a day,” he said.

“So, how much is one gram of gold worth?”I responded.

“Forty Euros (US$54.80).”

“One hundred Euros (US$137.00) a day? ” I couldn’t believe it.

“Yah mon,” he said.

The next settlement was 10 km away.

“So how much for a one way trip?,” I asked.

“One gram,”he said.

Uncomfortable silence.

Then, the Maroon boatman, who’d tagged along, suddenly chimed in demanding Euro 100 (US$ 137.00) for “services rendered.” I cannot repeat my response, but he went away without any “petit cadeau.” Harvey and I would be walking to the gold mines.

Walking out of town, we first had to clear a stinking garbage dump before a surprisingly intact forest began. But the rutted ATV track consisted of orange mud that, with one misplaced step, could suck off a shoe. Soon the drone of gas-powered hydraulic pumps blasting away in a river bottom with jets of water drowned out all sound of the forest.

In spite of Bensdorp’s wild reputation, Brazilian garimpeiros actually stopped momentarily to warmly greet us as we attempted to communicate: me in Spanish, they in Portuguese and Harvey in Sranan Tango/English. We were free to photograph whatever caught our interest. Like at Rosebel, the watershed had been widened and reduced to a desert. Sparse tufts of grass were all that could grow in the barren expanse. Virgin forest crowded in on each side of the watercourse. Though the Brazilians had not come to harvest timber, we knew too well that logging conglomerates from Asia were aggressively trying to enter Suriname to exploit its timber wealth.

Gold mines excavated by Brazilian “garimpeiros” gold miners, have progressed up a watershed to devastating effect further and further into pristine rainforest in the Suriname interior outside the boomtown of Bensdorp.

Gold mines excavated by Brazilian “garimpeiros” gold miners, have progressed up a watershed to devastating effect further and further into pristine rainforest in the Suriname interior outside the boomtown of Bensdorp.

Migrant Brazilian men of unknown visa status (many are known to overstay) mining for gold with high power water hoses deep on Maroon territory in the Amazon interior near Bensdorp, Suriname.

Migrant Brazilian men of unknown visa status (many are known to overstay) mining for gold with high power water hoses deep on Maroon territory in the Amazon interior near Bensdorp, Suriname.

Fouled pools of water stand beside a gold camp run by Brazilian “garimpeiros” artisanal miners in the deep Amazon in Suriname. Handmade sluice boxes are used to separate gold from the soil and river stones at the downstream outlet of an artificial pond of foul, likely toxic water. Bensdorp, Suriname.

Fouled pools of water stand beside a gold camp run by Brazilian “garimpeiros” artisanal miners in the deep Amazon in Suriname. Handmade sluice boxes are used to separate gold from the soil and river stones at the downstream outlet of an artificial pond of foul, likely toxic water. Bensdorp, Suriname.

We found no Chinese miners in Bensdorp but there were a half dozen trading posts run by Chinese merchants all from Fujian Province. They lived in their stores, raised up Asian-style, on posts. These expats were thriving and happy in Suriname, wisely profiting off the prospectors, not taking the risk of prospecting themselves.

As night fell, back in Bensdorp, Harvey and I returned to a riverfront trading post run by two outgoing young men from Fujian. Their store was large, selling every manner of shovel and tool a garimpeiro could ever desire. A Brazilian woman was settling a bill by laying out pure gold to be weighed on an electronic scale on the store counter. A flat-screen television, showing non-stop period-drama DVD’s from China, played to no one. Through a large doorway, in a darkened storeroom, two hammocks had been strung. The men worked, ate and slept in this trading post.

A migrant shopkeeper from Fujian Province, China talks with a cigar-smoking Ndyuka Maroon boatman as he pours fuel into a barrel for the multi-day journey down the Marowijne River to the coast. On the left, as a Brasilian “garimpeiro” gold miner (L) waits patiently. The boatman will pay for the fuel with nearly pure gold. Bensdorp, Suriname.

A migrant shopkeeper from Fujian Province, China talks with a cigar-smoking Ndyuka Maroon boatman as he pours fuel into a barrel for the multi-day journey down the Marowijne River to the coast. On the left, as a Brasilian “garimpeiro” gold miner (L) waits patiently. The boatman will pay for the fuel with nearly pure gold. Bensdorp, Suriname.

Bill settled, the merchant turned to a group of beer-drinking Brazilian men milling around in front of the shop. A downriver longboat, loaded with their supplies, was moored in the shallows. The boatman, a fit Maroon man, chewed on an unlit cigar as he watched the merchant carry two plastic jerry cans of gasoline strung from a shoulder pole down to one of several fuel barrels mounted in the bottom of the boat. Here was Suriname’s Deadwood, its Klondike boomtown. No one but the Maroons had any history here. Make your buck and get out, the environment be damned.

NOTE: If you are in New York, James’ “Mangaland: A Tokyo Retrospective” will be showing at Sous Les Etoiles Gallery thru January 31 2014. The opening is tonight, December 12, 2013, from 6-8pm.

PHOTOGRAPHS and text by James Whitlow Delano

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus