Notes

James Whitlow Delano – Third Dispatch: Tribes Losing Rainforest Battle to the Logging Conglomerates

Note: This is the third installment in photographer James Whitlow Delano’s series for BagNews Originals on the fate of the rainforest in Malaysia. You can see the two previous dispatches here.

The Baram River, the jungle thoroughfare for the indigenous Dayak peoples, snakes through the last great forest in Southeast Asia, the interior forest of Borneo, and into Penan territory. Not long ago, the Baram River and its tributaries were the only way for tribes like the Kelibits and the Penans to travel to the coast from Long Lellang. For a couple of decades, tons of top soil, mostly washed away because of intensive logging operations, have turned the waters the color of cafe latte.

The Baram River, the jungle thoroughfare for the indigenous Dayak peoples, snakes through the last great forest in Southeast Asia, the interior forest of Borneo, and into Penan territory. Not long ago, the Baram River and its tributaries were the only way for tribes like the Kelibits and the Penans to travel to the coast from Long Lellang. For a couple of decades, tons of top soil, mostly washed away because of intensive logging operations, have turned the waters the color of cafe latte.

Once again I found myself whispering about loggers, this time in a Borneo guesthouse washroom in Miri, Sarawak, days after leaving the Batek tribe. Sarawak is a semi-autonomous state within Malaysia and it controls many of its own affairs, including doling out profitable logging concessions. To keep this sparsely populated state from being overrun by migrants from the peninsula, all who enter must pass through a separate Sarawak immigration port of entry when arriving. This gives the state government one more layer of control over who can come in and sniff around, hence the “sotto voce” conversation between a member of an NGO banished from Sarawak, posing as a tourist, and me.

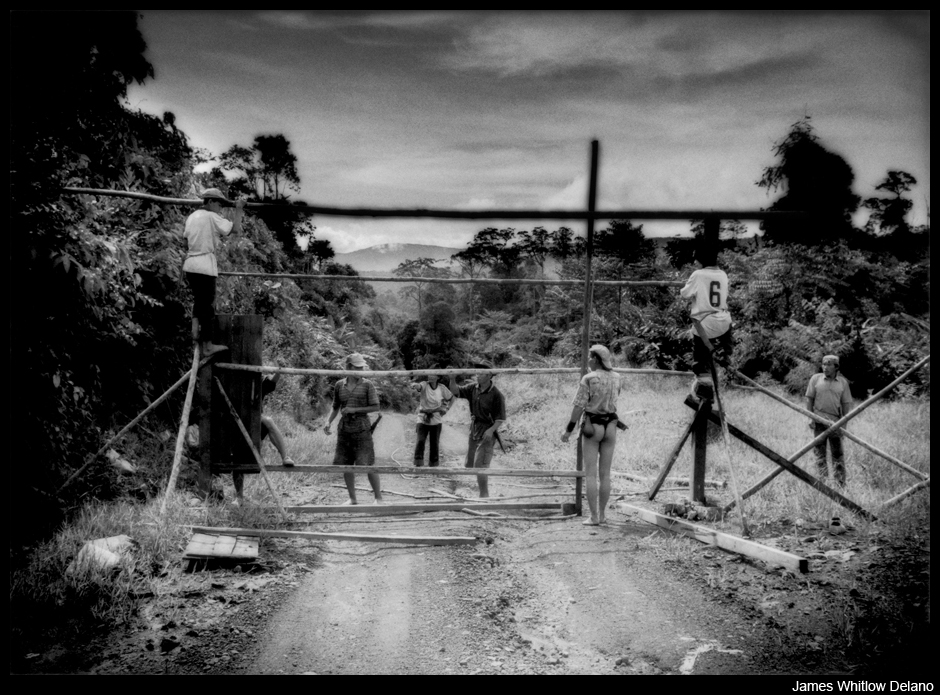

Penan clan from Long Kelamu build a barricade. The intention is to to block loggers from Samling Global Limited from accessing one of the very last tracts of virgin forest in the Malaysian state of Sarawak that is not part of a national park.

Penan clan from Long Kelamu build a barricade. The intention is to to block loggers from Samling Global Limited from accessing one of the very last tracts of virgin forest in the Malaysian state of Sarawak that is not part of a national park.

It was quietly confirmed that the indigenous Penan had erected bamboo barricades along logging roads near the remote upriver village of Long Lellang, used by logging multinationals, Samling Global and Shin Yang Group. In most countries, governments build roads but in Sarawak logging companies build them, that is, only if they are allowed to cut the trees. Local access is incidental.

Marudi is the largest inland settlement near Miri, about 25 miles as the crow flies. There is a lot of traffic between the two cities, mostly by air and by riverboat. The land link is by a phenomenally treacherous mud road through oil palm plantations. When it rains, which is just about every day, is almost impassible even by 4WD. I have had the misfortune to travel in a Landcruiser group taxi and nearly spent the night in a ditch with about a half dozen other four wheel drives that could not negotiate several steep hills. The Bakun Dam, on the other hand, is over 100 miles from the main coastal highway. It has a concrete surface the entire way to service the profitable (to the investors, that is) hydroelectric dam. I have driven the entire length of this road. There are no cities or towns along its entire length. Priorities, Sarawak-style.

Long Lellang is accessible by boat (two weeks), by logging road (12 hours by 4WD), or in one hour by Twin-Otter aircraft twice weekly. I chose to fly, which was also about 1/10th the price.

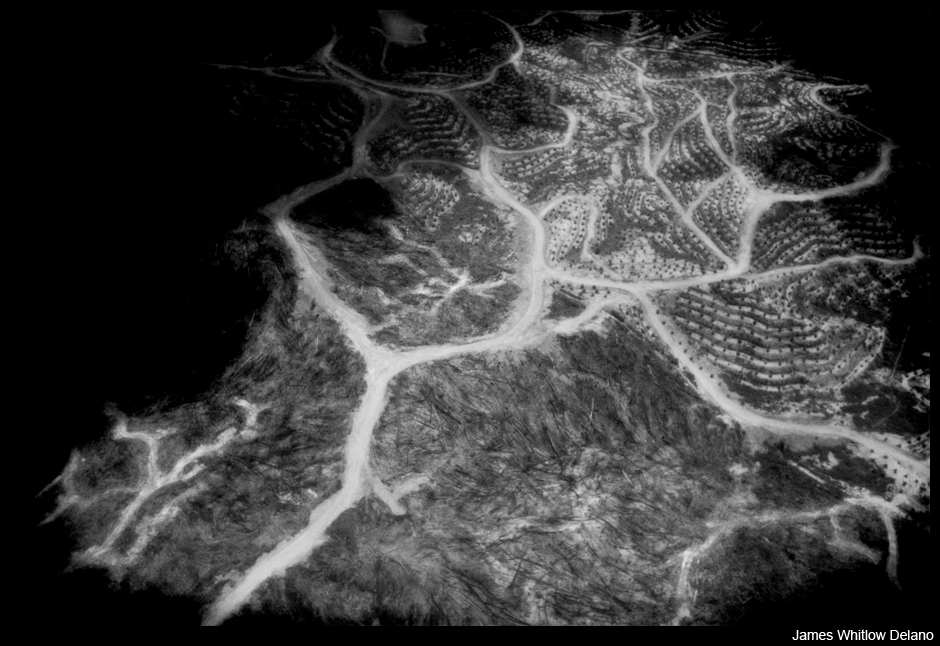

Logging road used by Samling Global Ltd. logging company pushes deeper toward one of the last unprotected parcels of old growth forest in the interior of Borneo. Near Long Lellang, Sarawak, Malaysia.

From the tiny aircraft window mile upon mile of oil palm plantation stretched out to the horizon. Then the forest became sliced by vein-like logging roads and the sinuous Baram River, choked orange with sediment. It should be the color of tea, transparent and tannic black-brown. Logging had freed the soil, just an inch or two deep, and had sent it and the sub-soil racing down into the river suffocating fish. An orange river means a damaged forest.

Most striking, however, was a massive logging truck super-highway, extending in a straight line through the rainforest below. The muddy quagmire, massive even from roughly 20,000 feet, was as wide as an LA freeway. Looking out over unbridled, industrial-scale exploitation over what used to be a wilderness no less than 25 years ago, that familiar knot returned to my stomach.

A logging road, seen from the air, slices through what until recently had been an untouched, old growth Borneo forest in a great, 130 million year old rainforest. Near Long Lellang, Sarawak, Malaysia. This is the homeland of the Penan people, upon which they depend for their existence, from which cures for many human disease may be contained, if the forest is not decimated by loggers and converted later to oil palm plantations. Already sediment severely clouds the area’s rivers. The soil in the virgin forest is exceedingly shallow meaning that most of the bio mass of a tropical rainforest is found in the living trees and plants. When the forest is cut, even selectively logged (as in this photograph), what little soil there is immediately turns streams muddy brown and, if clear cut and converted to oil palm plantations, there is almost no top soil left at all. Torrential tropical downpours, typical to the ever wet rain forests of Malaysia, quickly wash it all away.

A logging road, seen from the air, slices through what until recently had been an untouched, old growth Borneo forest in a great, 130 million year old rainforest. Near Long Lellang, Sarawak, Malaysia. This is the homeland of the Penan people, upon which they depend for their existence, from which cures for many human disease may be contained, if the forest is not decimated by loggers and converted later to oil palm plantations. Already sediment severely clouds the area’s rivers. The soil in the virgin forest is exceedingly shallow meaning that most of the bio mass of a tropical rainforest is found in the living trees and plants. When the forest is cut, even selectively logged (as in this photograph), what little soil there is immediately turns streams muddy brown and, if clear cut and converted to oil palm plantations, there is almost no top soil left at all. Torrential tropical downpours, typical to the ever wet rain forests of Malaysia, quickly wash it all away.

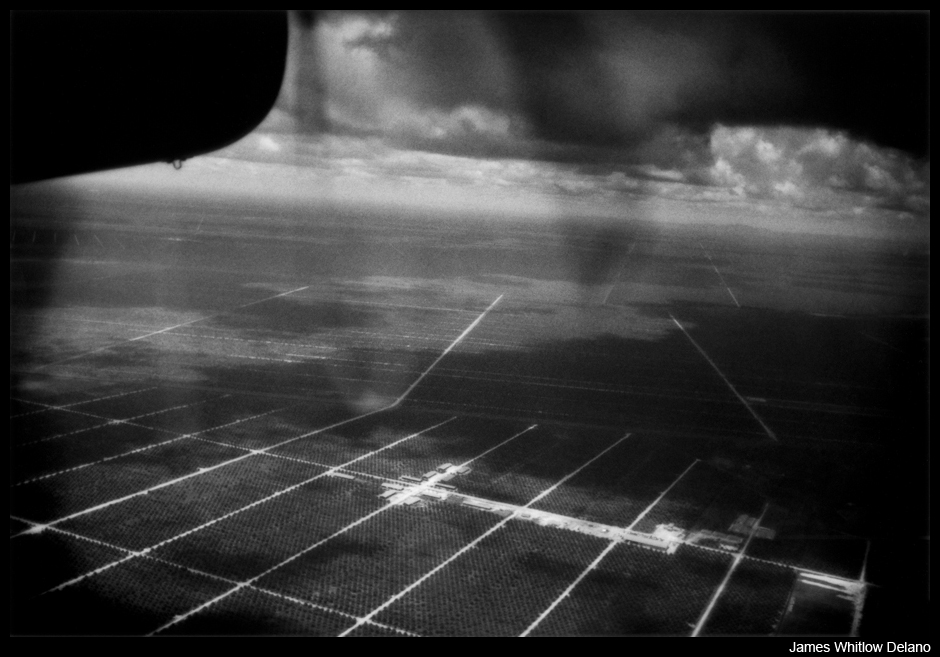

Clear cutting Borneo’s rainforest (bottom half of photograph) for conversion to oil palm plantations (top right quarter of frame) seen from the air near Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia. Oil palm plantations are impoverished “green deserts/” Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove of Princeton University, analyzing data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, found that 55-59 percent of oil palm expansion in Malaysia, used in part to produce bio fuel, spread at the expense of the rainforest. Between 1990 and 2005 the area of oil palm plantations in Malaysia more than doubled to 3.6 million hectares while Malaysia correspondingly lost roughly 1.5 million hectares of forest.

Oil palm plantations stretching to the horizon and to the Borneo coast seen from the air near Marudi, Sarawak, Malaysia. Once the rainforest has been logged out, conversion to oil palm plantations, a source of bio fuel, often follows.

The aircraft touched down on an airstrip, rainforest pressing in on all sides. Loggers (Shin Yang) had made a pass on one side of Long Lellang, which consisted of a largely abandoned Kelabit longhouse, a scattering of raised houses, a regional boarding school for Penan children and a medical clinic. The air was brilliant with light, scrubbed by billions of leaves filtering the air, giving it a springtime quality.

I hired a Penan guide, Balang Weng, who knew where to find the barricades and a plan was hatched to leave the next morning, me in my high-tech trekking shoes and Balang in his US$2 rubber soccer shoes known locally as, “Kampong Reeboks”. I felt fit and confident, with decades of trekking experience, as we marched out of town along the airstrip and up the logging road but then we entered the forest.Penan use trails no wider than animal tracks.

Trouble started immediately. My shoes had no traction at all on the myriad icy-slick surfaces. Balang walked straight up slopes of mud, I slid back as if on butter.Going down was worse with dense matts of mossy roots literally clothing the edge of drop-offs. Bridges were logs, coated with a transparent slime, 6 to 10 feet above boulders in shallow streams and the round boulders during stream crossings were the most slippery of all. When we entered a fallow slash and burn field chest-deep with grass and an unseen labyrinth of shin-bruising felled trees, Balang decided it would be better to endure the brutal sun along the logging road before I broke an ankle or leg. I would never walk in the Borneo rainforest again without cleats. You have been warned.

Balang Weng, a Penan man, crosses a stream in an old growth forest in the heart of Borneo on the way to a logging road barricade to try and keep Samling Global Ltd. logging company out of this unprotected forest, the traditional hunting grounds of his Penan clan. Selective logging has pulled out important trees, damaged the soil and silted up rivers reducing food for the Penan, including fish in streams and prey animals on the forest floor and canopy.

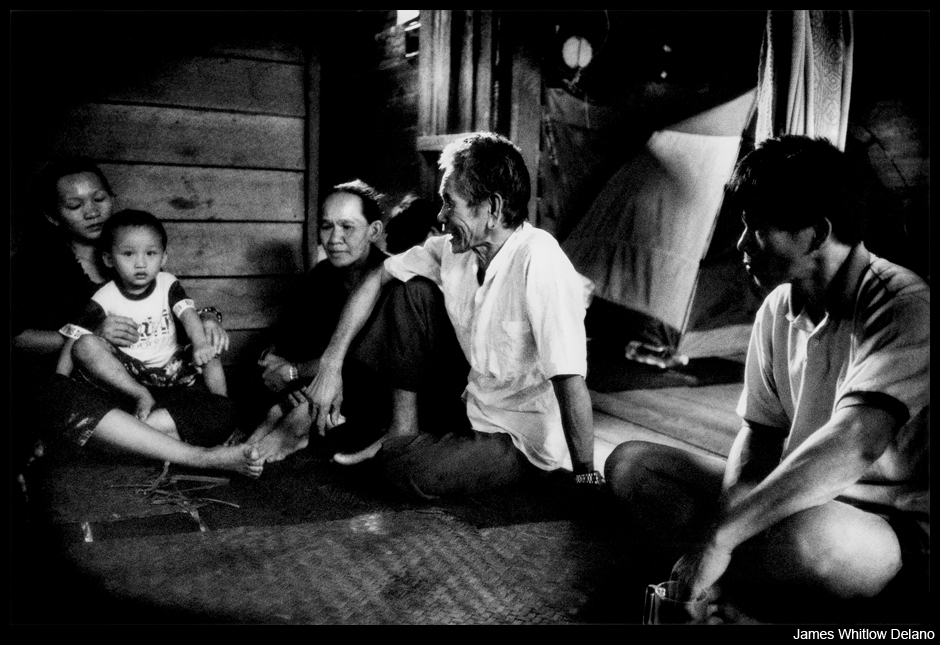

We arrived in the Penan settlement of Long Kelamu after a 6-hour trek. The Penan used to be a nomadic people but the forest can no longer provide full sustenance. So now they cultivate hill rice, sell the meat of wild boar and sometimes go to the coast for wage labor. We climbed up a log with notches into the house. The floor was made from split bamboo polished smooth by feet and provided the perfect springy surface on which to sleep. The Penan talked deep into the night about logging, with one older man reduced to tears discussing how Samling was coming to cut what little unprotected forest that was left.

Carefully we re-entered the forest, hiking for several more hours before finally reaching a rickety bamboo barricade. Still intact, the Penan had built it to slow the loggers’ advance. We found the Penan building yet another barricade along the main logging road on the return journey. Yet, loggers always come back with bulldozers and sweep aside any barrier in their path.

Talk about logging dominates local Penan and Kelabit communities’ daily conversations, as the Long Kelamu clan discuss construction of the new barricade the next day on a second logging road used by Samling Global which wants to coducting logging operations in one of Sarawaks very last unprotected old growth forests.

Ruthann, Philippus’s wife, working in the kitchen of their raised house, Long Kelamu, Sarawak, Malaysia. One or two generations ago, Penan did not live such a settled existence. Instead they roamed the rainforest following game or fruit that was in season.

What are the prospects of the Penan clan in resisting Samling Global Limited? What are their chances of blocking this logging giant from accessing one of the very last tracts of virgin forest in the Malaysian state of Sarawak?

According to Forbes Magazine, Samling’s father & son owners, Yaw Teck Seng & Yaw Chee Ming have an estimated worth of US$ 480 million. The per capita GDP in Malaysia is US$ 6,970 (World Bank). According to Survival International, there are roughly 10,000 to 12,000 traditionally nomadic Penan living in the forests of Sarawak in now settled communities. Even taking the upper figure of 12,000,, the entire population of the Penan people would earn only US$ 84 million per year, less than 20% the net total worth of the two tycoon owners of Samling Global Limited.

At the time of writing, I discovered that Samling, once listed on the Hong Kong stock exchange, had now privatized and delisted. Why does this matter? When a corporation lists on a stock exchange, it must publicly reveal all its subsidiaries to potential investors. Shin Yang never did this. One could surmise that Samling realized its critics had a much easier time charting its activities so it privatized.

Now, when you go to the former web address of this multinational corporation, only this message appears:

“Thank you for visiting our site. Samling Global Limited was privatized by way of a scheme of arrangement which came into effect on 15 June 2012. Its shares were delisted from the Hong Kong Stock Exchange on 20 June 2012.

The Company is now a subsidiary of Samling Strategic Corporation Sdn. Bhd.

For the company’s previous regulatory filings, please refer to www.sfc.hk and www.hkexnews.hk”

Voila, a behemoth disappears.

TRANSCRIPT and PHOTOGRAPHS by James Whitlow Delano. See previous dispatches here.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus