Notes

The Dutch Media's Immigrant Photo Drama

Even though the Netherlands have been known for their tolerant attitude towards “immigrants”, the last couple of years have seen several debates about the role of those immigrants in Dutch society. Second and third generations immigrants are often accused of not being integrated enough — a public opinion factor that, not unlike elsewhere in Europe, has added to the rise of several right-wing parties. Some problems are difficult to visualize with photographs. The “problem” with immigrants (in The Netherlands) is one of them. For a while now, I have been fascinated by one picture that is used in all kinds of Dutch news articles.

Especially the Elsevier paper (screen grab below) uses the picture often: in a report on fighting “nuisance” by Moroccan youth in the inner city of Helmond, in a piece about tackling youth crime by the municipality of Amsterdam, in a piece on a remark by Hero Brinkman about Muslims, in a piece about psychological help for dysfunctional Moroccan families, in a report about criminal youth in an Amsterdam neighbourhood and in a blog post by Afshin Elian on criminal behavior among young Moroccans:

The (currently no longer circulating) free newspaper De Pers was charmed by the picture as well. There the image accompanied a report about twelve thousand children whose DNA profiles are kept in database, a report that an imam believes that conversion to Islam can be a solution for many problems of Moroccan “street terrorists”, and a report about homeless youth:

But that’s not all. Even the consultancy bureau BMC used the photograph in a report about troublesome youth in Amsterdam:

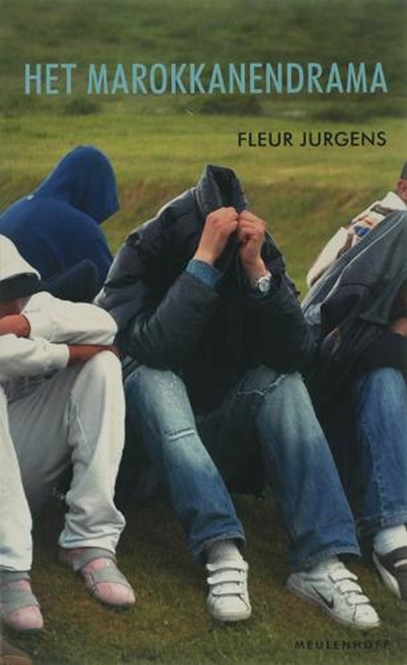

And even then we’re not done. Which photo is on the cover of Fleur Jurgens’s book The Moroccan(s) Drama? Exactly. The photo was taken from a different angle but shows the same situation and the same moment:

Now, what are we looking at?

Homeless youth? Criminal Moroccans? Moroccan families who need psychological help? Children whose DNA is kept in a database? Or maybe just Moroccan street terrorists?

It won’t come as a surprise. It’s none of those.

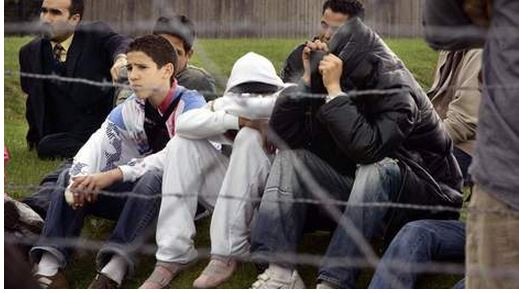

If you look at the pictures closely, you see that some details tell a different story: the barbed wire in the foreground and a part of a barrack in the background.

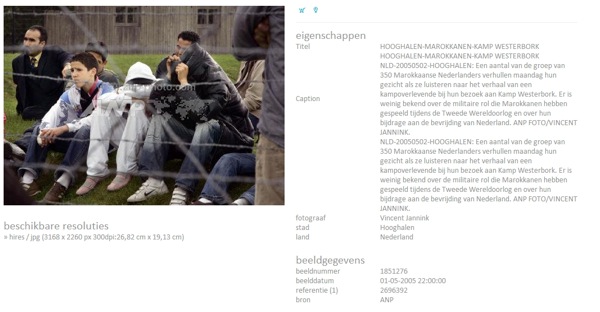

When I see barbed wire and barracks, I immediately think of concentration or refugee camps. By typing in those words in the database of the ANP photo archive, I found the original photo. After reading the caption I fell off my chair:

Photo caption: “Some of the group of 350 Moroccan Dutch hide their faces on Monday as they listen to the story of a camp survivor during their visit to Camp Westerbork (a Dutch WWII transit camp used to assemble Roma and Dutch Jews for transport to the Nazi concentration camps – Ed). Little is known about the military role that Moroccans have played during the Second World War or about their contribution to the liberation of the Netherlands.”

So what do we see?

A photo from 2005 showing some of the 350 Moroccan boys visiting the Camp Westerbork. But besides their background, nothing in the picture has anything to do with the news the photo is used for. These are just guys listening to a camp survivor. Even if there has been some “noise” during the visit (see here and here), that’s not what is in the photo. (More photos of the visit can be seen here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and over at the photo agency Hollandse Hoogte.)

Why is this photo being used for so many different stories in which the “immigration problem” seems to play a role?

It remains my speculation but it seems very likely that the editors have an image in their mind when they write a news story. They then search for a picture that matches that image. It is a logical process that I also regularly apply when I search for images to show during a lecture. I then also search for that one photo that best represents the image I have in mind. Chances are that I also occasionally show a picture of something which is not what I think it represents. Everybody makes mistakes.

However from journalists one could expect they also ask themselves the question: what am I looking at? Or at least they should have read the caption that explains what is in the picture. If they would have done so, nobody would ever have published this picture in this context and, above all, this painful misuse of a photo could have been prevented.

— Martijn Kleppe

* Martijn Kleppe works at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and recently defended his dissertation Canonical Iconic Photographs. The role of (press) photographs in Dutch Historiography (Eburon, Delft, 2013). This post originally appeared in Dutch on Photoq.nl and in English on Africa is a country.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus