Salon

BagNewsSalon: The Picture from Syria

Co-sponsored and underwritten by Victoria University in the University of Toronto

On November 15th, the BagNews Salon hosted “The Picture from Syria”: An analysis of the media imagery of the Syrian civil war. The purpose of the discussion was to better understand what media imagery from the Syrian civil war has to tell us about the situation on the ground, about photo access, the status of refugees, and the type of themes and visual narratives being framed by the Western press. Co-sponsored and underwritten by Victoria University in the University of Toronto, the program included a live feed, and student participation via Twitter, from a classroom in Old Vic. Below is a summary of the webinar.

Images and Selected Quotes

Produced for BagNews by Meg Handler

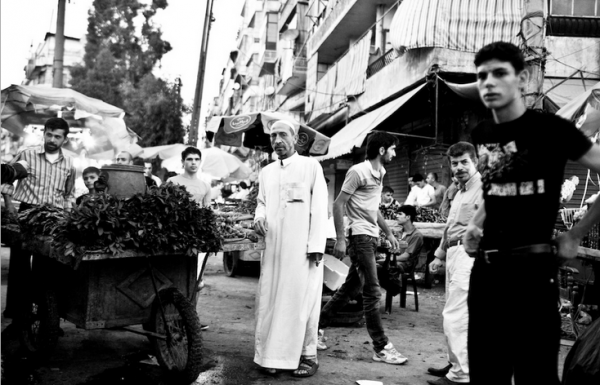

(photo: Daniel Etter / Redux. caption: At a local market in the Shaar area of Aleppo on Aug. 24, it’s business as usual. People carry on with their day-to-day activities despite the constant threat of air attacks and other violence.)

Michael Shaw: We thought this was really an important photo to start off with because it really shows civilians, it shows domestic life and it starts to give us a window, I believe, into what’s happening, not in terms of violence and sensational pictures of destruction, but really more of the day-to-day in Syria.

Lorette Steinberg: One of things that strikes me about this photograph is the contrast between the caption and the image because it talks about people going about ‘business as usual’ and when I look at the expressions and I look at the people looking at me, the viewer, I don’t see ‘business as usual,’ I see people who look very weary.

Nicole Tung: People in Aleppo either fled or they tried to adapt as quickly as possible after the fighting started. This photograph taken on August 24th was almost exactly a month after the actual war had come to Aleppo but obviously for over a year it had already been in people’s minds and, you’re right, they are weary. The expressions in the photographs are of one of concern, of weariness, but it’s surprising how much daily life you do see on the streets of Aleppo despite the potential for airstrikes and shelling to occur at any given moment. But Aleppo’s always been the business capital of Syria, so people kind of continue in their business-like ways. One of the common refrain that I hear form a lot of the Free Syrian Army complaining about Aleppo citizens is that they are very business-minded, they are money driven and their allegiances to the opposition are kind of in question because maybe a lot of them maybe didn’t want the war to actually come to Aleppo.

I actually visited Aleppo before the fighting began so I caught a glimpse of the tension in the air and the security that was placed around the city. There were checkpoints everywhere. It was very difficult to get around, but the cafes were filled with people smoking hookah pipes and having expensive meals in certain areas of the city. A month after that, when I remained there, most of those people had fled. The cafes were still open but they were empty and obviously most of the protests had taken place in lower class, working class neighborhoods. Areas like Salaheddine and Bustan al-Qasr which were the first ones to start really getting shelled pretty heavily. These were the neighborhoods that been the most defiant before the fighting actually began.

But when I go back now and speak to people even in the old city who are presumably, most of them are traders or working blue-collar jobs, whenever there are Free Syrian Army fighters around they are a little more reluctant to talk but when you get them alone they tend to be quite open and honest that they don’t know really what good this war has brought. They don’t foresee an end to it and they think it’s ruined their livelihoods. It’s ruined most everybody’s livelihood in Aleppo.

Walid Hamarneh: I’m frustrated, not necessarily about this picture, that’s a larger issue. I am frustrated basically because it seems to me that most journalists have become interested in what is happening in Syria and in the Syrians simply because of the destruction and they are only interested in the destruction. They are not so much interested in the in the majority of the Syrians, whom they never see, whom they’ve never talked to … for different reasons.

I’m not trying to blame them for that, necessarily, but this emphasis on the destruction only, this emphasis on this tiny part of the Syrian population, and forgetting what is happening in the larger picture in Syria, the daily suffering of people. This is why I thought that this picture is an interesting picture. Because it shows us aspects of how people are suffering but how people are trying to survive.

It seems we need to get out of these dichotomies in which we see things as black and white and good and bad. And I’m not trying to defend anybody. I think that what we have in Syria now are basically bad and bad, if you like or bad and worse rather than good and bad. But we need to show this. We need to show this to people. We need to show basically how the ordinary Syrian, if there is anything that is ordinary in Syria, how these people can cope with the situation, how they live.

Tara Sutton: I have sat in edit suites with editors based in London or Toronto and try to fight with them that “there are actually five stories that are going on here” and “no, this isn’t the bad guy or the good guys and there are so many different ….” — they don’t really want to know it because they have to sell to an audience that probably doesn’t know anything about the country and is probably watching a show about a cat who can sing next to it, so it’s very frustrating … what is sold or what you can actually put out depends so much more on editors than our own personal choice. I think all of us would probably want the newspaper full of whatever country we are in; we just think there are so many stories that can be told, but we are not making the decision.

(photo: Asmaa Waguih/Reuters. caption: Members of the Free Syrian Army use a catapult to launch a homemade bomb during clashes with pro-government soldiers in the city of Aleppo, on October 15, 2012. )

Tara Sutton: It’s a great shot, I think. Regardless of the fact that it shows violence, there’s a level of realism and there’s a level of the sort of asymmetrical nature of that war that is really captured in that shot. Something you wouldn’t believe if you didn’t see it.

Nicole Tung: The Free Syrian Army fighters are using all the kinds of devices they can their hands on or make or come up with. They’re using them on the front lines. It’s not an uncommon sight to see this. They’re lobbing homemade bombs with their own hands. Sometimes they make mistakes and they injure themselves in the process. This is the primitive nature of what it’s come to, essentially.

Tara Sutton: As soon as I saw that I thought, that’s going to land wherever it’s going to land. It’s guerrilla warfare and that’s sort of the option. IEDs, they don’t know what they are going to blow up either. That’s sort of the nature of guerilla warfare is that it’s not accurate and it’s not targeted. But I would assume that if they are fighting in a neighborhood that they know slightly or they are from, they are probably not aiming it into a place where they feel that civilians or their neighbors are, they are probably aiming it where they think it will hit the forces they are fighting against. I’m sure they make errors, but it seems pretty clear from the photo.

Michael Shaw: A lot of the photos that we are seeing are, I think, very sympathetic to the rebels, naturally sympathetic to the rebels, do not belie the kind of complexity between the factionalization for example. I’m wondering if …and maybe it’s relevant in this photo…. if there’s a sense that photojournalists who are going in there are almost embedded with the rebels. To the extent that that may or may not be true, how much is there interaction with or are you running into government forces or government representatives, and then is there a kind of tension that exists too because of some sort of cognizance on their part that there exists a kind of …. I don’t want to call it embedded … but that there’s a sort of sympathy to the rebel side? Does that play in anyway in terms of this photo or when shooting in Sha’ar or Aleppo?

Nicole Tung: The city is massive and for the most part you are free to travel around on your own, you don’t have to travel around with the Free Syrian Army fighters in their pickup trucks at all, in fact, I spent a week at this hospital doing my own thing with the doctors, with the civilians, and I wasn’t embedded with any of them so I didn’t feel like there was a natural sympathy towards anybody except with the civilians who clearly were facing the brunt of the shelling and the airstrikes. And that was … you try to be neutral in this situation but there’s also a very clear line between what’s right and what’s wrong and clearly things that were happening to the civilians were very wrong and I felt like I needed to document that. And many journalists have documented that, but you know it’s … today maybe two dozen people between Israel and Gaza die but on a daily basis in Syria it’s between 100 and 200 people, most of them being civilians either shot by snipers, killed by airstrikes or shelling, or just caught in the cross fire.

(photo: Nicole Tung. caption: August 24, 2012. Ahmed, 12, waits with his uncle (right) near the body of his father, killed by a shell in Sha’ar. Ahmed, who saw his father die, was also wounded in his back by shrapnel.)

Nicole Tung: Very interestingly, this graffiti in this photo speaks to the factionalism within in the Free Syrian Army. The graffiti reads: Jubhat al Nusra and then, I think, on the bottom it reads Allahu Akbar which is ‘God is greatest’. But Jubhat al Nusra is one of the brigades which is the most extreme; allegedly has ties to al Qaeda and has in its ranks fighters who are not friendly to foreigners or journalists at all. And it’s becoming a fast-growing brigade all across Syria. They are known for being really hardcore fighters, really at the forefront of the fighting and that’s why many Syrians actually admire them and want to join them and emulate them because they are very hardcore fighters. So that’s one part of the photo.

The other part of the photograph is, obviously, this 12-year-old boy has just lost his father. A shell hit their home in a nearby neighborhood and his father was killed and he saw this happen. He was in the same room with his father. There was a big rush of casualties coming into the hospital that day as happened many days in August. But this boy was particularly striking to me because he was confused; I think he could recall what happened but he was in a little bit of denial. He was sitting in the hospital earlier before I took this photograph with a very listless look on his face trying to figure out what was happening. And this body was laying out on the street and it was his father so as soon as this boy came out of the hospital, his uncle was … people had surrounded him and started asking him what happened and I recall him saying that “we were at home and the shell landed and I saw my father then I was here.” So he was also injured in his back by the shell and this was a daily occurrence this is a daily occurrence.

Walid Hamarneh: In the middle is the word qademwen which means ‘we are coming.’ So wait for us … which is interesting.

I see that we are wittingly or unwittingly, willingly or unwillingly bringing the picture – even when we talk about the civilians – from one side. And I see that there are others in Syria who are in government-controlled areas who are suffering, who are being killed – not only by Syrian forces, but by the Free Syrian Army. So we don’t have angels here and devils there. This is what I am trying to say. I have not seen one single image in the Western press showing all those churches that were destroyed, showing all those areas that were pillaged, that were completely destroyed by the Free Syrian Army.

Nicole Tung: It was bad enough when I went there before the fighting started when there were checkpoints around the city and there were spies in Shabihah — everywhere — so I think the situation would be even more difficult now to cover from the government side especially going in illegally – trying to get into government-controlled neighborhoods, which I haven’t attempted since August. I definitely feel like these are issues that need to be covered. I just I wish I had a good answer to give you to say how I know how to cover them, in fact.

Also, the activists there are obviously very clearly pro-opposition, very pro-Free Syrian Army. They rarely talk about the atrocities that the Free Syrian Army are committing, they rarely if ever talk about the torture, the executions that they commit, so it is a problem, it’s hard to rely always on activists’ accounts because they tell you in a very restricted way what they want you to hear as well.

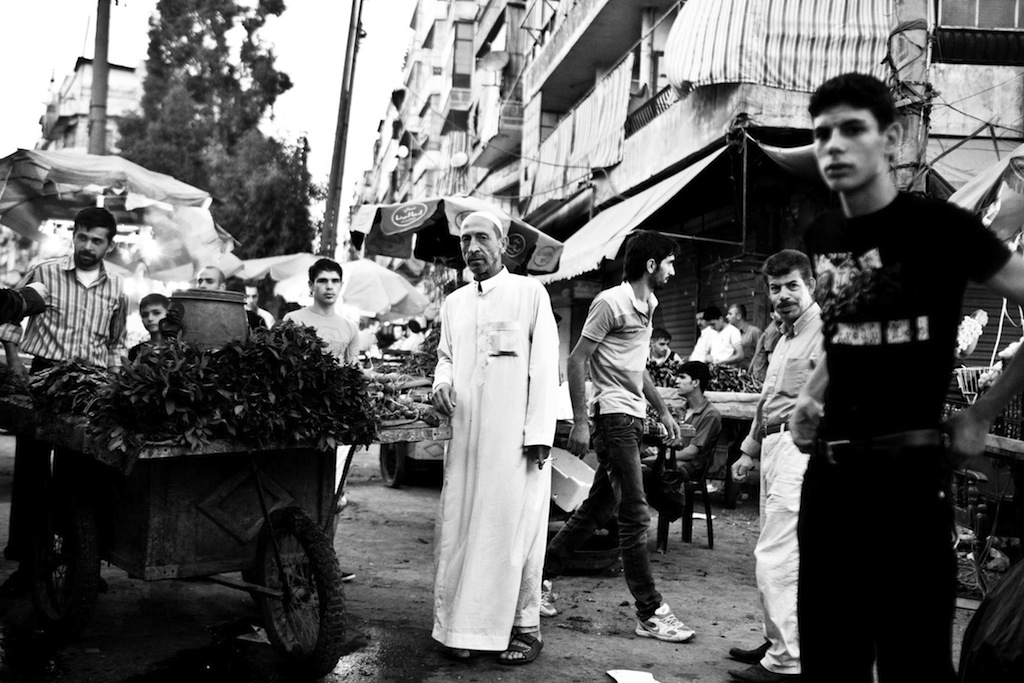

(photo: Bryan Denton for The New York Times. edited caption (part of larger photo-story on Syrian rebels published at NYT Lens): After a failed bombing, Syrian rebels drive to Aleppo where they waited at the abandoned home of police captain. One of the fighters looks through a wedding album found in the home; he did not approve of some of the dresses the women were wearing.)

Walid Hamarneh: I think I have to add something to this. First of all, this brigade is not a part of the Free Syrian Army in the sense that they are not former military that deserted. They are the group of very fundamentalist Islamists who just came together and who disagree with Jubhat al Nusra, but they are not former soldiers, they are mostly people who belong to certain very fundamentalists Islamist groupings. These people are not your typical Muslims. A decent Muslim would of course not look at these private photos of family because it would be considered indecent. But with some of these fundamentalists Muslims, they feel that it is their religious duty to police how people behave, how people eat, how people drink, and this is why it is a part of their duty to see these things and to tell people what kind of clothes they should wear, what they should eat, how they should move, and so on and so forth. So in that sense, from their perspective, not the Islamic perspective, but the fundamentalists’ perspective this is a duty, actually, rather than anything else.

Tara Sutton: That’s what bothered me about the caption of this picture. I thought it played into stereotypical ideas about ideas people have about Islam and women and it isn’t clear and, as Walid just explained, it’s much more complicated. My first reaction as someone who has spent some time in the Middle East is that someone who was a true Muslim would never do that. And then you your saying that there is a layer deeper, but that’s not explained to us in the caption at all.

Lorette Steinberg: Even though it’s hard to see his expression, his being on the sofa and this being a quiet moment in looking at these photographs, I think it’s like the psychological rape of this family and these people. I certainly see that in this photograph. What I’m struck by is how much we don’t know, because the culture is unknown to us except in superficial ways or as an introduction. That is incredible. As much as we try to learn more about what is going on and we memorize names of cities and we look at the maps to see where it’s going on there is always something near that an outsider is going to miss. In this case and also in Nicole’s photograph. I’m struck, especially, with both of those.

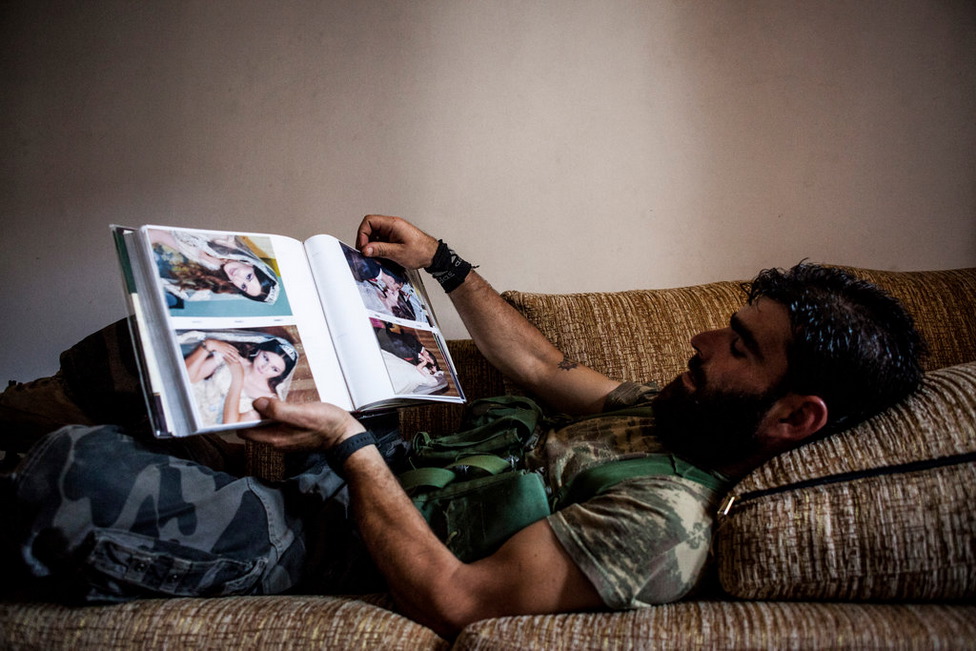

(photo: Mustafa Ozer/AFP/Getty Images. caption: Syrian refugee children flash V-signs at a Turkish Red Crescent camp in the Altinozu district of Hatay, near the Syrian border.)

Tara Sutton: The thing about this photo that grabs me first of all are that this could be any refugee camp in the world, where you have bored kids hanging out. The other thing that it makes me think about is the branding of aid, which is how agencies love to just stick their logos on everything they do which I find sort of frustrating.

I spent all the time that I was doing the refugee stories in Jordan at a town called Mafraq, which is about an hour from the border with Syria. And I was going there in the Spring and Summer of this year because I saw a mounting refugee crisis that was getting no attention from the outside world and many of the refugees had fled Homs and Da’raa so they had lost their papers and they were frightened of registering with anything official. The UN figures were about 7,000 but the Jordanian figures — which were the ones I tended to trust because they were the ones that were actually allowing them into the country — were 140,000 and they were growing over the summer of a rate of about 500 people a day and now are at about 1000 a day, if there’s a lull in the fighting, although I think last weekend about 18,000 people fled in a 48 hour period.

What really struck me the most when I started hearing the stories of people that had arrived in Jordan was that they had literally been hunted out of the country and the level of fear that they had. Most of them, well practically all of them, couldn’t actually leave through an official border post so they called it ‘going through the fence’ and they would walk this 5 kilometer path over rocky mountains and then be met by Jordanian customs agents who would then take them to a transit facility to process them and many of the women that I interviewed were widows or their men were still inside Syria fighting and they had large numbers of child and they would arrive with absolutely nothing because they had not been able to take a thing with them so it was a really destitute situation that they were in. The town that I worked in — there was no camp in the beginning. There was no camp until August. There was a very, very slow response from the big aid organizations and all the assistance they were getting was cobbled together by small local charities, the Muslim Brotherhood, concerned citizens groups from various gulf states would send some convoy of boxes of food that would have about 300 parcels and they would have 10,000 people living in tents that they’d made out of old coffee bags and living in people’s garages with no water, no ventilation. It was not a good situation. I think it’s improved slightly in Jordan now because at least there are camps set up so there’s some codification of when people get food and they get cooking supplies and stuff but for a long time you had a group of really traumatized people living in a really desperate way.

I don’t know if that picture speaks to what I saw; you kind of want to go in to each tent to learn the story but it was because … I live in Jordan, I was able to go repeatedly over and over again so I really tried to get personal histories and it was a good way to kind of piece together what was going on. I often used a map of Homs which is where they were all coming from and have them show me where they had fled from place to pace and could then verify what they told me, because often it was too incredible to believe. That was my initial feeling.

Nicole Tung: On that note, I haven’t spent that much time in the refugee camps, but I do know for a fact that Turkey has been very tightly controlling which international organizations can come into help, Whereas Lebanon, Jordan, and Iraq have been quite, I don’t want to say casual about it, but they are not restricting, whereas Turkey is hands on, very full on, with the image that they are giving to the world and hence you see that every single tent has the Turkish Red Crescent logo on it. I don’t see any other international organizations operating on a scale such as the Turks are doing and there is a reason why Turkey wants to project this particular image to the world and to the Syrians.

Walid Hamarneh: Concerning the camps in Turkey. The camps in western Turkey are very much controlled by the Turkish government and they are in good shape for one very important reason, the majority of the refugees in that area are ethnic Turkmens. They are people who are very, very close to Turkey and Turkey is trying to use them in its political game in Syria. Whereas most of the refugees who are in the refugee camps in the east are mostly either Arabs or very few Kurds but mostly Arabs or mostly Alawis – that is Turkish Alawis, not Syrian Alawis, which are very, very different. I think this speaks to the reason why everything is controlled in the refugee camps in Turkey because Turkey wants to make sure that its own groups are well protected, well taken care of so that they can go on playing their political game in Syria for the future.

The Full Edit

Take a closer look at some of the images from our larger photo edit.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus