Salon

BagNewsSalon: "The Visual Chemistry of Kony 2012"

Sponsored by Open-i

On May 20th, in collaboration with Open-i, the BagNews Salon hosted “The Visual Chemistry of Kony 2012”: An analysis of the viral video campaign by Invisible Children. How do visual campaigns like the Kony 2012 viral video backfire in their success? What made Kony 2012 so visually sticky? How do the images fuel viral compassion so detached from the facts? How do images like the one by Glenna Gordon of the producers touting guns undermine the narrative within?

Images and Selected Quotes

Co-Produced for BagNews by Ida Benedetto

General Discussion

Benjamin: One of the criticisms of the Koney film is the lack of context. By looking at these images as stills without the sound because it was a FILM (that is the context in which we see these frames) could we be accused of doing a similar thing?

Glenna: I think it’s a valid point but I also think it’s a valid practice for us to slow it down enough to look at individual frames. One of the things the film does so effectively is deliver images so quickly that you aren’t processing them on a conscious level. We are de-contextualizing them by looking at them on an individual level. Otherwise, you don’t get to see what is in fact going on in the film.

Lina: Invisible Children has been held up as a prime example of transmedia, which is the extension of a core story over different distribution channels through participation and collapse of audience and authorship. What’s they’ve been able to do with transmedia originally comes out of marketing and storytelling. Invisible Children has been able to consistently engage an audience over 9 years. Unfortunately it’s a poor example of transmedia activism. This video takes symbolic activism and turns it into marketing. That’s why this discussion is so interesting; we are thinking about how we “market” activism or how we create activism through the use of imagery and symbolism. It’s all just moving all so rapidly.

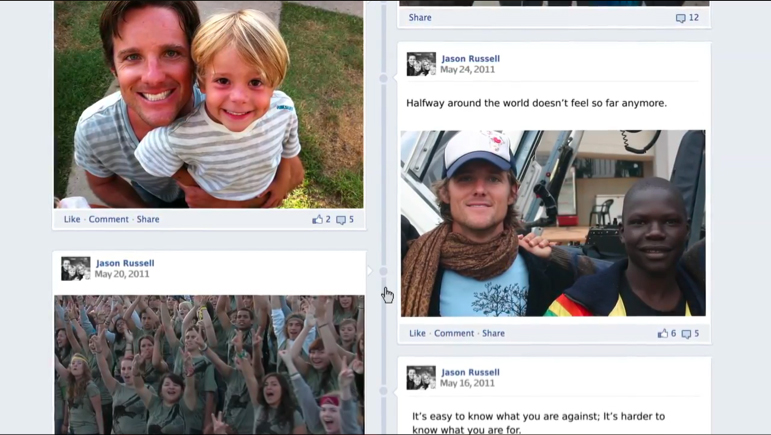

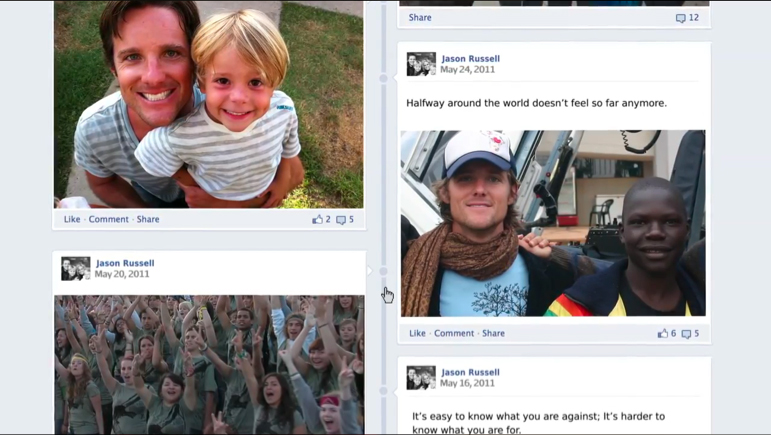

Facebook Timeline

Lina: Facebook mashes up the personal with political with the professional in problematic and interesting ways. I find social media tends to blur those boundaries. The advantage is the personal becomes the professional and political. It become so much more immediate… This seems to be the way that we’re going to be creating content flow for a very long time. I don’t know if we’re supposed to get used to it or if we’re supposed to get more nuanced about it.

Glenna: This is where Jason is giving you, the viewer, the chance to experience half way around the world feeling not so far away. When you look at the caption on the photo on there right of Jason and Jacob, it makes it all so acceptable, when in fact half way around the world is very far. This page is laying the groundwork for making the narrative something that it sounds like you can achieve by just being on Facebook.

Lina: Just because half way around the world doesn’t feel so far anymore doesn’t mean that the activism is any GOOD. Just because you’re on twitter and you support the Arab Revolution, just because you’re signing a petition… What does that mean exactly? Half way around the world isn’t so far anymore. That’s actually a beautiful thing but what does that mean?

Glenna: It IS far away. I think that the idea that it’s close is a basis for bad activism, if i want to help my sick neighbor, I can bring them some chicken soup. That’s an easy and wonderful gesture. If I want to send some chicken soup to someone in Africa, that’s a very complicated thing. Conflating those two things leads to the idea that we can just send our old shoes to Africa. That’s why I think this is a bit problematic.

Russel’s Son Looking Through Photos

Loret: There’s something about the mashing of ideas and the mashing of images with everything equalized that’s really early hard for me. Would he show this child lynching photographs? The poor kid doesn’t know the difference between Koney and the bad guys in Star Wars, which is what the child said in one of the questions. In many ways, it trivializes what’s actually going on there.

David: We’re told that if a 5-year-old boy can grasp the issue and make the judgement about right or wrong and what his position is, we should be able to make that judgement as well. It fits into that very classic notion that by making things visible, people will act on them. That notion needs to be questioned.

Lina: I was reacting more to the rescue narrative, that I your father am going to go make the world a better place by saving these people. I didn’t really get the sense that we were being asked to look at the conflict though the eyes of the child, but that we were being fed that same fairy tale in a different way.

Michael: One thing we’ve talked about is geographic dislocation happen virtually. This came up with the still of the Facebook stream. Here, you’re looking at a temporal dislocation as well with a photo of Jacob and an 8 year old image of Koney.

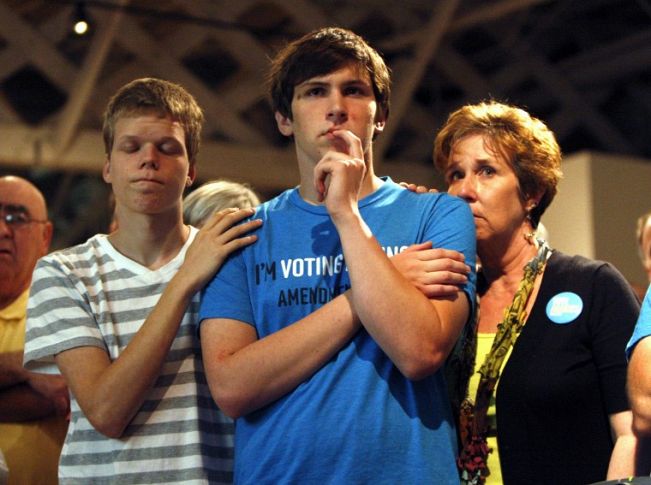

Mass of Students in Matching t-shirts

Loret: One of the things that’s problematic with the whole campaign is the idea that you too can have a t-shirt to show that you care. I have a colleague that once said that he doesn’t do documentary photography for this reason. People go to an exhibition and feel something. They buy the book, put it on their coffee table at home and think they’ve done something.

David: It’s hard to avoid the fascist aesthetic of this: people with their arms raised in uniform wearing red shirts. That’s part of the militarization of the Invisible Children campaign. They even describe their own people as constituting an army for peace. The idea of militarization stretches to the way they want to respond to the problem because they support a military solution to the LRA.

Nate: The peace into war, war into peace is a very common flip.

Benjamin: They also have a religious context. If you consider the army for Jesus and the way that religious people use the idea of army, it’s very different than a fascist context. That’s much more the tradition that Invisible Children is coming from. I’d say they are coming from a religious angle more than a fascist one.

Lina: It feels like marketing to me, like something I would see at a music festival. You could put a corporate logo on this and you might ask people to pick up their Coke cans and make a peace sign. The conflation of marketing images with activism is interesting and problematic.

Murky view of people sleeping in a shelter

Lina: These images can be motivating to a certain extent depending on the context. These kinds of visuals didn’t work for Rwanda, didn’t work in Darfur. In the subsequent years, when we think about Rwanda and Bosnia, we think about holocaust memory. These images start to build up not through sense of horror but rather a sense of history.

Ida: One thing I find particularly painful is how different this is from images of youth and community in the U.S., the communities that the video is trying to appeal to. We see lots of light in those images. There’s lots of action and engagement, very much like the last image we saw. All of the images of community in Uganda look like this; they’re extremely passive, largely anonymous. There’s not much activity going on, just lots of suffering. I have a very hard time believing this the complete picture. Yet, the video does an amazing job putting images like this together to convince us that the only site of action can be from outside of Uganda.

Lina: This image is very much in a continuum with genocide and atrocity images. What happened with the LRA was definitely a war crime, but it doesn’t fit the legal definition of genocide. We have to be careful about how we use that term given the legal ramifications. It’s an uphill battle sometimes when you work with people and organizations with very large budgets and a lot of engagement capacity to try and parse out those definitions. They just won’t have it.

Benjamin: Good point Lina .. context around … and thats why KONY worked to a certain extent, because they built a context that appealed to an audience. The failure in Dafur and Rwanda maybe was a failure of storytelling.

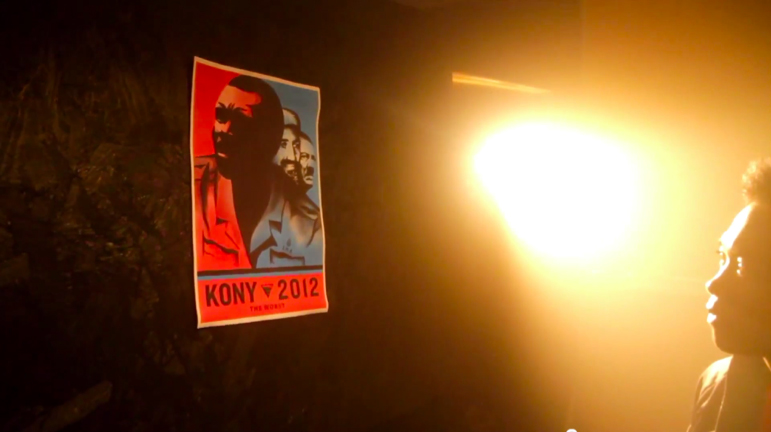

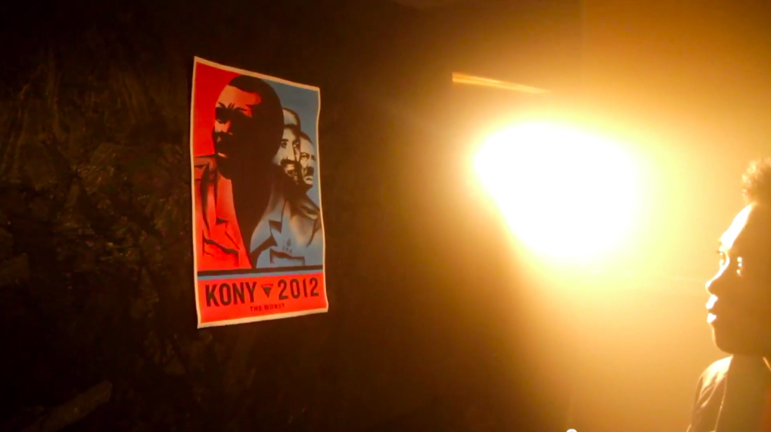

Poster on Wall

Michael: This was one of those frames that went by so fast it was almost subliminal. This comes at that end as a call to action. Go out and plaster the world and cities with billboards etc, etc.

Glenna: This is a very created image. It went by so quickly that I didn’t catch it when I watched the video. The wall looks like a handmade mud wall unlike what you’d find in a U.S. suburb. The light source looks like what you might see in a village where a small bulb is doing a lot of work to like up a huge space. In this image is the idea that Ugandans are participating, that half way around they have the same poster. I don’t think that is true. What I think is interesting, having just been in Uganda, is there isn’t a single Kony 2012 poster in Uganda.

David: So much of this video is a classic “Heart of Darkness” enlightenment colonial narrative about our position as white saviors vis a vis Africa as a homogenous place in a different temporal zone. These are the little video moments that confirm that.

Glenna’s shot of ‘the band’

(photo: Glenna Gordon. caption: The founders of Invisible Children — Bobby Bailey, Laren Poole, and Jason Russell — posing with guns alongside members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), who have fought against the LRA. 2008)

Michael: This is interesting because of the militaristic aspects of the group. Rhetorical theorist wrote about the convertibility of war and peace. We can treat war as a special case of peace. Given Benjamin’s comment on the guy in the middle doing a Rambo impersonation, how that kind of can be in the name of seeking peace.

Glenna: I was covering the peace talk of the Ugandan government and the army for the Associated Press. We were all expecting Koney to arrive and sign a final peace documents. We waited round for several days hoping that he would sign. There was a whole lot of boredom with playing cards, smoking cigarettes, shooting the shit. One afternoon, this is how Invisible Children decided to entertain themselves. I stumbled upon this scene and thought it was a significant moment. I worked with a colleague to write an article about what we thought Invisible Children’s dubious practices were. We pitched it to some 12 places and could not get anyone to bite. I forgot about the photo and moved on professionally. Now when the video went viral, the photo went a bit viral too. I’m glad that I took the photo. I’m glad that it is casting doubt on their motivations. Last month, I met with Invisible Children’s director in Uganda Julia Croak. She asked me to retract the photo. I defended myself saying I took a photo of something that was happening and if there upset that the photo exists the regret has more to do with their actions than it does with the existence of the photo.

Loret: Photographers get blamed for reporting what it is that people do. I don’t buy the boredom makes us pick up guns and be cool. There are a lot of people who would have been in the situation who wouldn’t have posed with guns.

Hands raised in favor of pardoning Kony

(photo: Sara Terry. caption: When asked who would be willing to forgive LRA leader Joseph Kony, a crowd of hundreds at a meeting with delegates from the LRA responded by raising and waving their hands. The LRA’s month-long tour of meetings with civilians was the first time in Africa that a rebel movement has apologized and consulted with civilians about appropriate means of justice.)

Ida: In this case, we’re seeing action in progress, an action coming from the people the Koney 2012 video purports cannot act on their own behalf. This photojournalistic image is clear evidence that they can, and that they have a take and that that take is not in alignment with what Invisible Children is advocating.

Christine Lorenz: Marvelous followup to the previous group shots. This does not have the stagey and narcissistic feeling of the Invisible Children images.

Studio Image

(photo: Andrea Stultiens. caption: Kitgum Abayo Kopie, a photo studio in the town of Kitgum, Northern Uganda.)

Ida: This is a photo studio and what’s happening here is very different form what’s happening on Facebook according to Invisible Children. The expectations about how people represent themselves are different, how they share those representations both inside and outside their community. I can’t exactly read how this photo studio works, it looks like there’s backdrops on at least three of the walls. We don’t know who is being photographed and who’s doing the photographing. The image is a triptych, which draws attention to itself as a representation. My inability to read exactly what’s going on here speaks to the fact that communication and culture can’t be completely understand outside of one’s own cultural milue. This world of diversity and ambiguity is not what is represented in the Koney 2012 video.

David: It shows you the depth and reach of local agency, which of course is the antithesis of the Koney 2012 video. The Ethiopian famine of 1984 produced the bandaid Live Aid phenomenon. The music single that got people mobilized then was “Do they know it’s Christmas?” Seeing the Christmas trees in this studio, I love the idea that they do.

The Full Edit

Take a closer look at some of the images from our larger photo edit.

Reactions