Notes

History and Herstory: Pie Town Pics Revisited

Critics of feminism have long suspected that the ultimate goal of the movement is to get rid of men. Their fears seem to be confirmed by artist Debbie Grossman’s “reimaging” of Russell Lee’s iconic photographic series portraying families in the rural New Mexican community of “Pie Town,” circa 1940. According to Time magazine’s LightBox blog, Grossman was inspired by the story of Doris and Faro Caudill, pictured above. According to one biographer, Faro “had been more of a burden than anything else to his wife.”

That account served as a springboard for Grossman, who transformed the photographic record of Pie Town so that the town was inhabited exclusively by women. Here is her reimagined photograph of the Caudill family:

Grossman’s image turns Doris into a rugged frontierswoman, capable of both preparing the meals that necessitated her apron to maintaining the sturdy fence that forms the backdrop of the photo. Grossman also subtly changed the hue of the sky—turning it from a dour and cloudy gray to a more optimistic, rich blue. In fact, the entire reimagined photo is brighter, signaling the fact that Grossman’s Pie Town is designed to function as fantasy. One feature visible in both photos is the red nail polish on Doris’s thumbnail—a sign that in both the poverty-stricken Pie Town of the past and the utopian herstory of Grossman’s imagination, some trappings of feminine beauty remain intact.

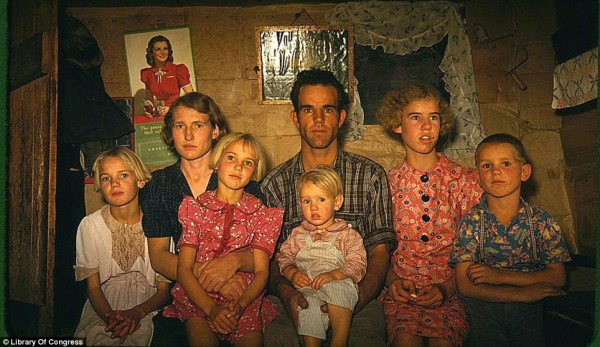

Grossman’s collection also contains a revised portrait of the Whinery family, originally comprised of a husband, wife, and their five children:

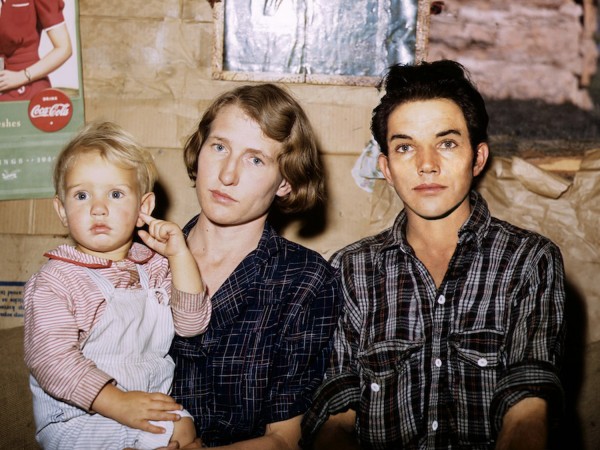

Grossman chose to alter the picture to contain just the parents and one child, introducing the family as “Jessie Evans-Whinery, homesteader, with her wife Edith Evans-Whinery and their baby.” Grossman told Time that she “like[s] it that viewers can look at the images and see a world that appears real, but that didn’t actually exist. More specifically, I like that viewers can see a very contemporary kind of family—two married women with kids, for example, as if it has a precedent in the past, and as if it were part of the American historical archive.”

The family as Grossman reimagined it not only exists without men but also limits the number of children in a family, eliding the fact that the large families of earlier eras often resulted from needing many hands to tend the farm. The brightness of the photo, the attractiveness of its subjects (check out that bone structure!), and the tight frame dispel some of the markings of poverty that Lee’s original shots document. In Lee’s photo, we see the cramped quarters in which the Whinery family lived as well as their attempt to brighten the space with a piece of threadbare ruffled cloth framing the window, next to a make-shift mirror. Interestingly, both photos feature the ideal of conspicuous consumption, with the CocaCola poster and its portrayal of idealized feminine beauty looming large.

By “queering” the Whineries, Grossman suggests a version of family that might have emerged in mid-20th century Americana had social proscriptions been less intransigent. Additionally, although her pictures likely will be read by some as a stereotypical bout of feminist man-hating, the images reveal the ways in which our understanding of women expands when men are removed from the picture. It is an historical fact that women often did “men’s work” on the American frontier but when women are pictured alongside men, their contribution often fades into the background. For example, a contemporary newspaper article about Lee’s photographs captions the original Whinery picture as follows: “Facing life head on: Jack Whinery, homesteader, and his family in Pie Town, New Mexico, October 1940.” The male subject is named and given the title, “homesteader,” while the female subject, like the children, remains unnamed. She is cast in a supporting role in this post-Depression-era drama, while “Jack” plays the lead—“homesteader” and protagonist.

Feminism is not about hating or erasing men. It’s about telling women’s stories. Grossman’s reimagined Pie Town deploys an imagistic switch that allows more stories to be imagined. Only after a story is imagined can it be accurately told.

— Karrin Anderson

(photos: Debbie Grossman—Julie Saul Gallery. First image: Library of Congress)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus