Notes

Alan Chin on the Middle East: Ghosts of Suez and Srebrenica

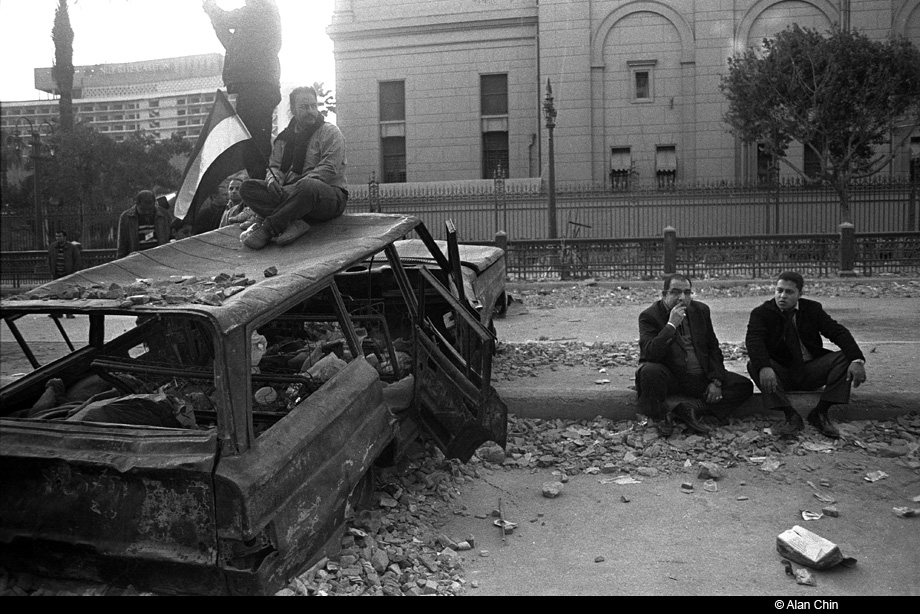

Destroyed vehicle, Egyptian Museum, Tahrir Square, Cairo, Egypt.

With UN resolution in hand, France, Britain, and United States are launching air-strikes on Qaddafi’s forces in Libya, decisively changing the balance of power on the ground yet again in what has been an extraordinary season of surprises. Assumptions, allegiances, and desired outcomes get ratcheted up another notch, way past any red-line warning in a tangled web. So much is at stake, so many mutually contradictory motives are at play all at the same time, that it is hard to know what to think or predict.

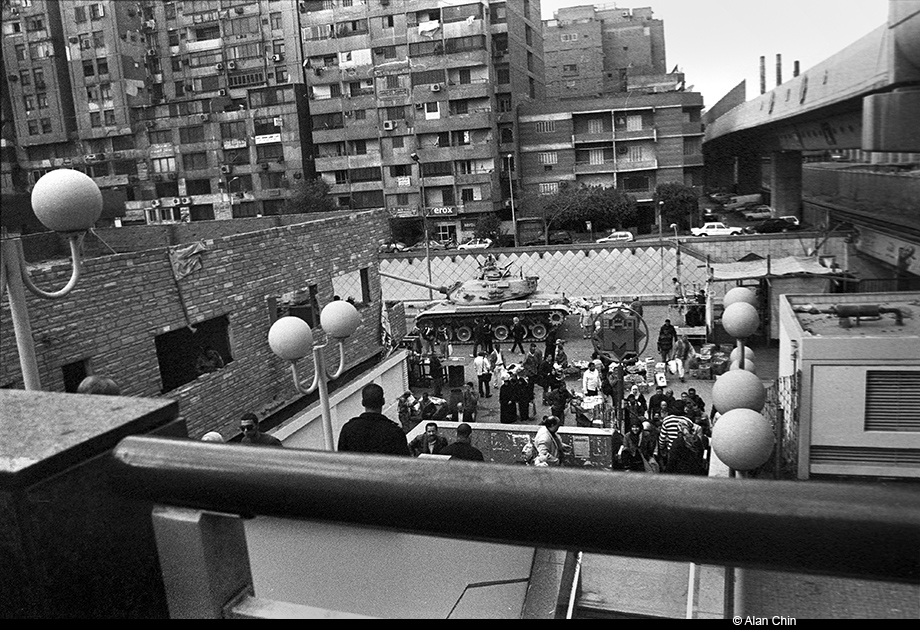

Barricades next to the Egyptian Museum by the 6 October Bridge and overpass, Tahrir Square. The statue is of General Abdel Moneim Riad, killed fighting Israel during the War of Attrition in 1969.

The ghosts of Suez and Srebrenica haunt the Middle East today. In 1956, the British and French colluded with Israel against Egypt after Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, and despite military success, were blocked simultaneously by the United States and the Soviet Union, which also took advantage of the crisis to brutally suppress the Hungarian uprising in Budapest. It was the last time that the British or French took the lead on anything, and the French reacted by letting the Americans often go it alone, while the British were driven into an ever closer sidekick role to the US. That’s precisely what happened most recently with the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and no small factor in Tony Blair’s eventual fall.

A few short days ago, a version of this scenario looked like it was unwinding once more: Despite Sarkozy’s recognition of the Libyan rebels and strong talk, it seemed that Obama was choosing discretion as the better part of valor, and the chance of the UN passing any kind of no-fly zone resolution was dropping with each hour as Qaddafi rushed to finish his reconquest of eastern Libya. But then the bad memories of Bosnia kicked in. In 1995, peacekeepers and the Bosnian Muslims they were supposedly protecting in the Srebrenica “safe area” begged for air-strikes on a Serbian ground attack. All that frantic diplomacy resulted in a single ineffectual sortie by two Dutch F-16s, and more than 6000 Bosnians were killed soon thereafter.

Along with Rwanda in 1994, the failure to support Iraqi Shiites in 1991, and the sense that Western responses have been consistently a step behind the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions this year, Obama changed his mind after the Arab League requested action. The UN Security Council quickly followed. Even as street fighting erupted in downtown Benghazi, French jets bombed armored columns and American Tomahawk missiles rained down on strategic targets.

Yet in the political confusion, there seems to be no actual coordination with the rebels and no overt declaration to hit Qaddafi personally. And in what seems like an odd case of buyer’s remorse, Amr Moussa, former chairman of the Arab League and candidate for Egypt’s new presidency, said, “What is happening in Libya differs from the aim of imposing a no-fly zone, and what we want is the protection of civilians and not the bombardment of more civilians.” Fair enough, but what exactly did he think the Arab League was approving? Surely not an effort that would have been purely symbolic. In the short term, intervention has stopped Qaddafi in his tracks and certainly saved the revolution in Benghazi. The long term is anybody’s guess.

Egyptian guest-workers fleeing Libya carry an ill compatriot to the border gate, where they handed him over to waiting Tunisian medics. Ras Ajdir, Tunisia.

Personally, it has been an excruciating several weeks since I had to leave the Tunisia-Libya border after watching tens of thousands of mostly Egyptian guest workers flee in a humanitarian emergency. Qaddafi has continued to control the frontier and prevent journalists like myself from entering Libya by that route. Many of my close friends, colleagues with whom I have shared the joys and frustrations of our uncertain profession in the Balkans, Iraq, and Afghanistan, have been detained, gone missing, and been beaten, first in Egypt and now even more frighteningly in Libya. I feel guilty for not being with them, as well as embarrassment at my own selfish desire to always want to be at the center of a “big story.” Photojournalism is simultaneously a noble, ambitious, and perhaps pointless calling, yet we never question our faith and our own ability to do the best that we can. But I am thinking about it a lot.

In Tahrir Square, activists hurriedly reinforce a speakers’ platform with wood planks as it became crowded.

Tahrir Square, Cairo, and the Egyptian Revolution already feel like ancient history, my own witnessing of it a sideshow obscured by the deafening violence that has followed next door. The heady hope and celebration seems a distant memory. I know that this is only a passing reaction; that the long view will prove what we are living through to be an epochal moment on the order of 1848, 1968, or 1989. Sweeping movements of ideas are coursing through an entire region. Millions of lives will develop differently now for the next generation. Close-up, though, it feels purely speculative to venture any deep analysis or assume any wisdom, other than to reflect on history and its echoing discontents.

The Egyptian Army deployed in Giza.

So writing from the comfort of New York, I am reluctant to hazard any guesses on what will happen next, humbled by the enormity of what I saw through the small window of my lens, and anxious about my comrades. I have to stop myself from checking the news and my email every few minutes.

–Alan Chin

PHOTOGRAPHS by ALAN CHIN (all photographs February 2011)

To see entire BagNews series on Egypt and Libya: Middle-East Uprising 2011

Next post: The Revolution Continues

Previous post: Fresh To My Virgin Eyes

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus