Notes

Alan Chin in Cairo: Getting My Cameras Back

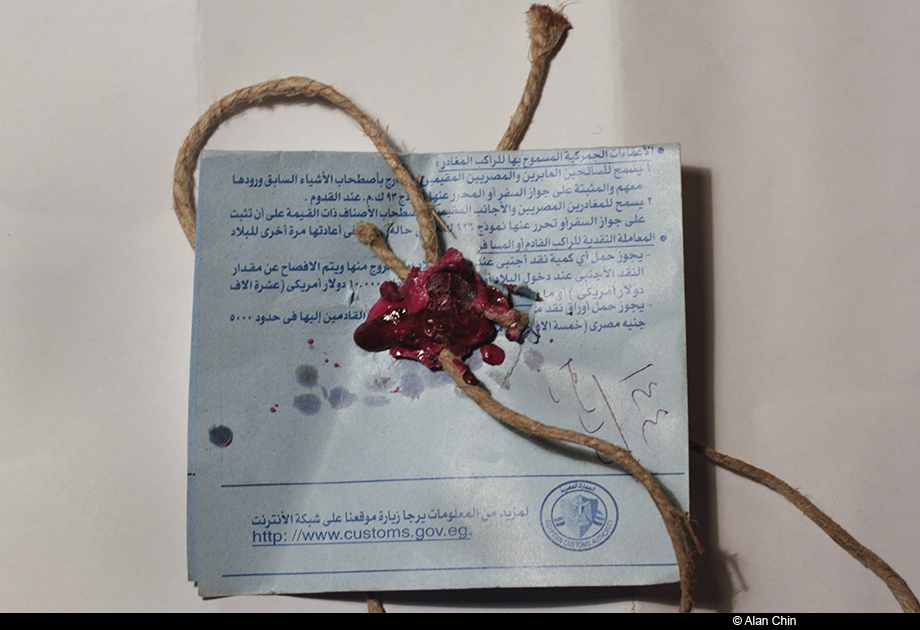

Seal on my equipment. The twine was used to tie the straps and zippers of my bag together. The wax was melted with a piece of burning newspaper.

As I recounted when I first arrived in Egypt, the police at the airport impounded all of my cameras and lenses as part of their spasmodic effort to censor and curtail the international media spotlight on the pro-democracy movement. After carefully writing down serial numbers in triplicate, customs officers placed my equipment into a room already bursting with cameras, bags, and boxes labeled: BBC, CNN, ABC, and so on.

It didn’t stop us, of course, but it wasted a lot of time, and provided a small insight into everything that’s wrong with entrenched bureaucracy. I started trying to get my cameras back the very next day. American Embassy officials did their best at the airport, but to no avail. Then they wrote me a letter, clearly identifying me as a journalist, and they stamped it with official seals. I took this letter to the Egyptian government press office:

“I have to get my equipment back,” I said.

“Yes, we admit that this is very unprofessional, but right now we are unable to help you,” replied the press officer, speaking perfect English.

“I have a letter from my embassy.”

“I know, sir. Many journalists have many letters from many embassies.”

I started laughing. I couldn’t help it. But he remained deadpan: “Please fill out the application for your press card, and then we’ll see.”

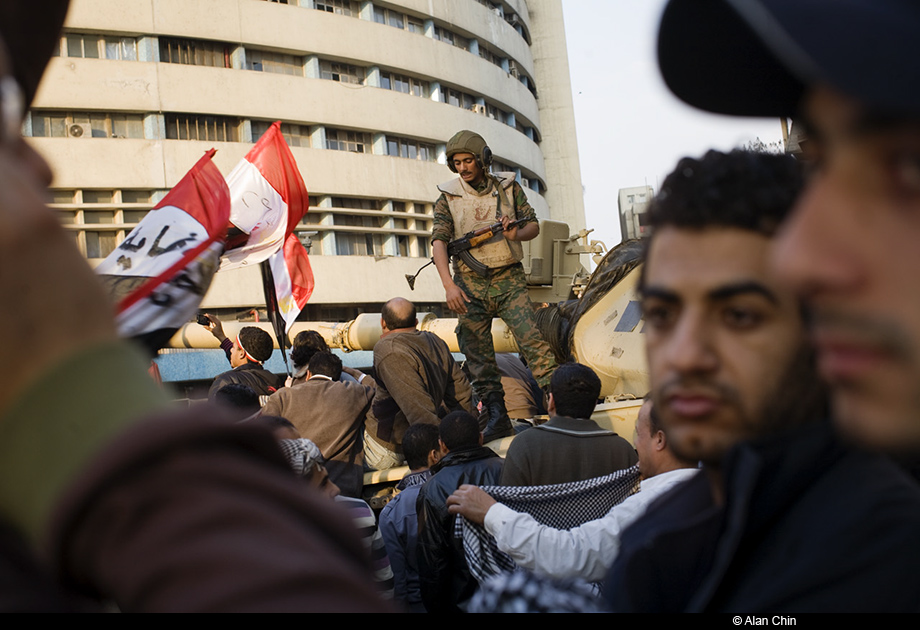

What else could I do? I did as instructed, and in the following days, this press center, located in the TV building on the Nile Corniche, where I was supposed to pick up my accreditation, became a focal point for protest as heavily armed soldiers held back an increasingly angry crowd. The very office where I might acquire more stamped documents was bristling with machine-guns from its balconies.

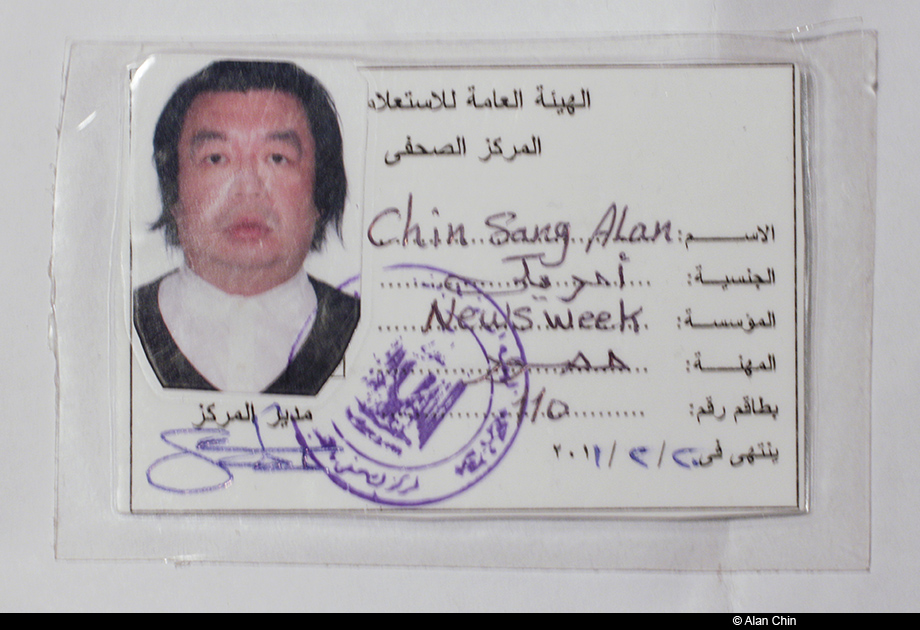

Then Mubarek fell, and I picked up my newly minted Egyptian press card after all. I had phone numbers for various customs and press officials, and they told me I needed another letter from my embassy that specifically says I would re-export the equipment; that I wouldn’t sell it in Egypt. So I bothered the patient diplomats again, who were gracious enough to help out once more at short notice. I had the press center stamp this second letter.

So along with my friend and colleague Moises Saman, on assignment for The New York Times, who I had come in on the same flight with and also had his gear confiscated, we trundled out to the airport. And they told us that we might have our papers in order, but that the relevant office is only open from 10 am to 2 pm, and we were already too late!

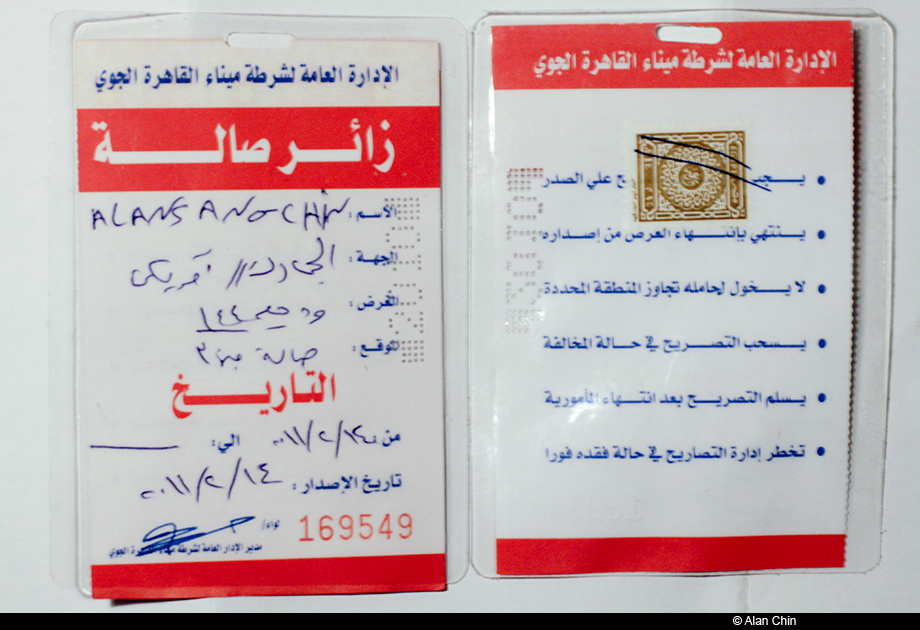

Passes to enter the customs area. Note the stamp for the fee.

The next morning, with the excellent help of the Times’ Dawlat Magdy through this entire process, the struggle truly began in earnest. We each paid $2 to get the pass necessary to get into the customs area of the airport. They gave us nicely laminated cards. Then, $3 for the application form. This form was taken to another office and stamped. While we waited, six or seven other journalists appeared. Two were in line ahead of us.

Our bags were retrieved from the room. An officer opened them and counted all the equipment against the list. He almost dropped or broke several cameras and lenses; we had to help him out. We were feeling confident now. But again we were told, “Five minutes…”

Another official came and REPEATED this process. This guy, we were told, was assessing the declared value of each item and judging it accurate or not. In the meantime we wrote down our personal details again on another piece of paper. We were getting impatient. One of the ladies walked by us with a sheaf of documents held up to cover her face, and said to us, “I’m not here. You can’t see me.” So many of us had harangued her with so many entreaties that she was laughing at us. We laughed at her.

Finally, we had to pay $5 for the “storage fee” since our stuff had been there for a week. And then we signed our names again in the Big Book, were given another piece of paper to leave, and we were done. Five hours had gone by, not including the days before and the trips to the press center.

At no point was a computer or even typewriter used. Handwritten (at times I lent them a pen), with carbon paper, they painstakingly copied data from one piece of paper to the next. We tried to count the number of people we had dealt with: the officers in their ill-fitting uniforms with polyester ties and cheap metal badges on their sleeves, the sardonic women, the chain-smoking clerks taking our money, and we lost track at fifteen. They’re paid $150 a month or less. We certainly lost count of the number of documents.

It’s easy to laugh about bureaucracy. Woody Allen and Kafka are a natural, if unlikely thematic pair. But Egyptians have to deal with this every day of their lives. Compared to being detained or beaten as so many journalists here have been, this was ultimately a relatively mild ordeal. But it kept us from doing our jobs for several days; it’s kept this country from developing accountable civil society. And in its more sinister forms, it’s meant that people disappeared into prison, are watched, questioned, and harassed.

–Alan Chin

PHOTOGRAPHS by ALAN CHIN

To see entire BagNews series covering Egypt: Middle-East Uprising 2011

Next post: On The Tunisia-Libya Border

Previous post: The Metro Stop Formerly known as “Mubarek”

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus