Notes

How to Read a War Carpet

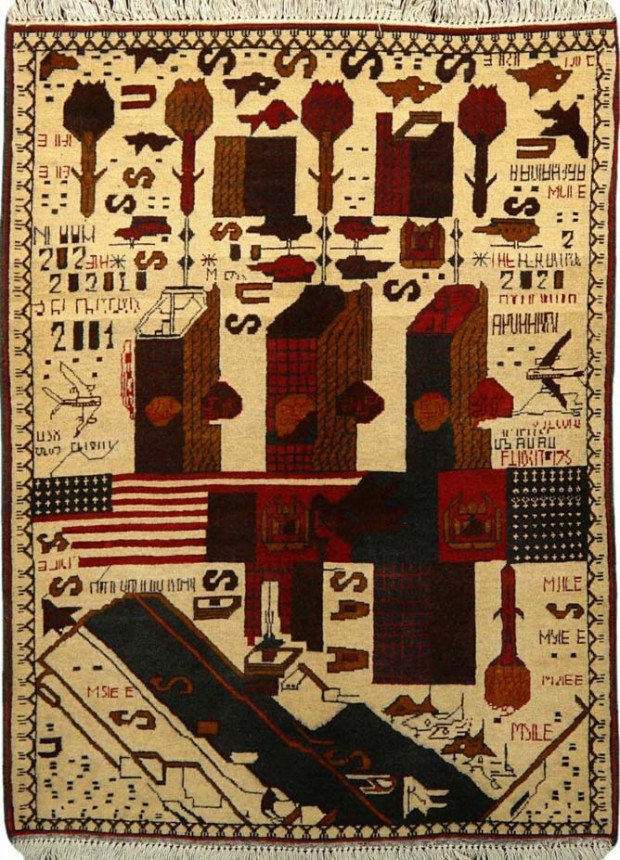

The most controversial and confronting of the many categories of Afghan “war carpets” made since the Soviet invasion in 1979 were those which first appeared in early 2002 and which memorialized the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. Hundreds, maybe thousands of these small mats were made out of poor quality materials, reportedly produced in the regions to the north of Kabul. They were made in an attempt to cash in on the anticipated numbers of foreigners appearing in Afghanistan in the wake of Operation Enduring Freedom and the NATO-led ISAF operations, which began to impact on Afghan society from November 2001 onwards.

The original version of this carpet was so precise that it could have been designed on Photoshop. (It probably was.) These mats were made by hand, each probably taking three or four weeks on a loom with continuous cotton wefts. The weaver would finish one, roll down six inches, and start the next one, in what was probably the most exploitative of circumstances. In 2007 there were still similar examples on Chicken Street which had not yet been cut apart, and at first glance it was hard to believe they were not the product of some kind of mechanical reproduction. They are in fact still woven by hand, in the laborious pixel-by-pixel knotted pile method, as have oriental carpets for thousands of years.

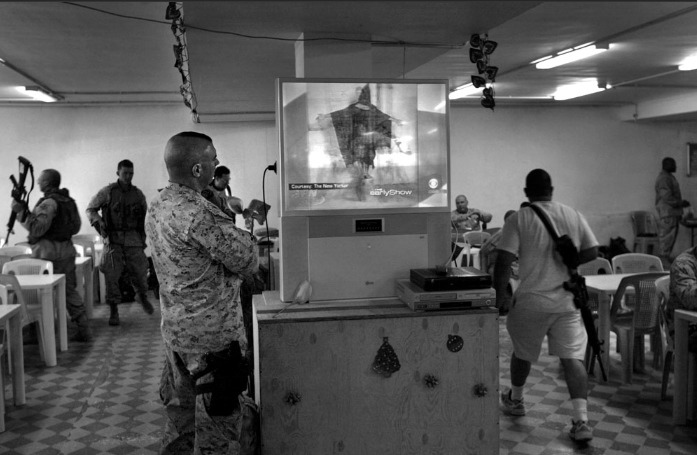

This is the archetype of a 21st century souvenir artefact. Before they were to be found in rug stores in the west, in early 2002 they had already appeared on eBay, at premium prices, marketed by online dealers based in Pakistan. When the market realised how many had been produced, the price plummeted, and within a year they could be bought for the (inflated) price of shipping plus a dollar. However once they appeared in the flea markets of New York, a controversy arose which raged around their motivation or intent.

While objectively their iconography had been designed to appeal to the west, ostensibly to recognize the horror of the act, and the heroism of the survivors, for some the sense of communal grief was so strong that they could not be seen as other than opportunistic and exploitative. Despite the fact that they sold well, and had attracted significant publicity, the dealer who first sold them came under virulent and threatening criticism from a range of political positions.

Here’s how you read the war carpet in its original form:

• The twin towers of the World Trade Centre are depicted in quite precise isometric perspective, with the impacts of the two airliners, left and right, just as they had been seen around the world on television and other media.

• The date and the flight details of the two airliners are also precisely written in English (“first impact”, “second impact”).

• The towers are montaged over the map of Afghanistan, colored green, the sacred color of Islam. The foreground band of the montage is derived from a US-produced propaganda leaflet, showing the two flags of the USA and Afghanistan united by the white dove of peace.

• USA is written vertically between the base of the towers, just above the obliquely rendered deck of one of the US aircraft supercarriers involved in Operation Enduring Freedom. The carrier showes fighter planes taking off, plus a Tomahawk missile rising up on the right hand side of the field. The missile is headed, presumably, for Tora Bora or the other sites targeted as al-Qaeda strongholds.

• The letters USA are repeated on the deck of the carrier. The first generation of these rugs (the most precisely-rendered versions) also included the headline “THE TERRORISM WAR IN AMERICA” and “AFGHANISTAN”. Thus the language, format, and iconography are all designed to appeal sympathetically to a foreign audience.

Eight years later another version of the carpet has appeared, now held in a private collection in Montreal. Such is the nature of the manual reproduction of Afghan carpets that a carpet is copied from another, over and over again. In this process images change, are simplified, and morph into new forms. The people (often children) who make the twentieth (or hundredth) copy of a design are therefore likely to have no idea of the significance of the iconography or motifs they are laboriously reproducing.

In this case we see the culmination of a process of progressive abstraction, where the maker has clearly lost contact with almost all of the significant references made by the original design. Generations of reproduction produced by copying from previous copies has resulted in an almost incomprehensible outcome – with three towers, missiles proliferating as a row of flower-shaped forms, helicopters flying upside down, text disintegrating.

This is, in a sense, tradition in action. Forms and motifs have dissolved into pattern. Tradition has reverted to its norm.

Nigel Lendon is an artist, curator, historian and cultural critic at the Australian National University. Together with Tim Bonyhady he holds an Australian Research Council grant to research the tradition of Afghan war carpets. He authors two blogs, Iconophilia (www.iconophilia.net) and Rugs of War (http://rugsofwar.wordpress.com/). Further information on the Afghan war carpet tradition may be found at the site for Max Allen’s Battleground exhibition at the Textile Museum of Canada (http://www.textilemuseum.ca/apps/index.cfm?page=exhibition.detail&exhId=271) and at Kevin Sudeith’s warrug.com (http://www.warrug.com/)

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus