Notes

Obviously, the "Iraqi Mind" Has yet to Catch Up with the "Iraqi Opportunity"

Moises Saman/New York Times

At least David Brooks was willing to acknowledge the trash removal still leaves something to be desired. Otherwise, the NYT columnist cheerily announced this week that nation building works. Specifically, that the $53 billion spent to reconstruct Iraq is going quite well, thank you. Not surprisingly, Brooks led with economic indicators, quoting the IMF on the country’s progress since 2003. (Gee, we might ask, what happened in 2003?) He then added for good measure statistics on oil production, cell phone ownership, and the like.

It seems that what is good for business is good for Iraq, and that the past can safely be forgotten.

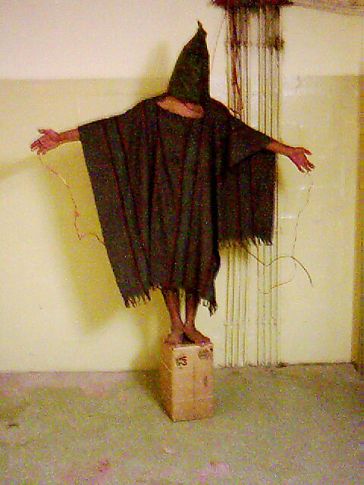

Out of sight, out of mind, unless you lost your son to the sectarian violence unleashed by the US occupation. To be fair to the Times, they presented the other side eloquently with this front page photograph and an accompanying story on the painful search for those victims still lying in unmarked graves. Other stories have chronicled how the reconstruction funds were squandered by imperial mismanagement, corruption and waste, how the country’s civil infrastructure remains devastated, how the security and political arrangements remain tenuous at best, and how military insurgency is on the rise again. Brooks, however, must not read the Times. In his account, there is no memory that reconstruction was needed because the country had been wreaked by the US invasion and occupation (and before that, another war and a decade-long blockade).

His most unconscionable oversight, however, is to deny the permanent human damage caused by the invasion.

Brooks allows that “the Iraqi mind has not caught up with the Iraqi opportunity” and then faults their lack of social trust. Besides hitting a high mark for hypocritical condescension, this argument makes light of the human heart and its most intimate bonds. (You’d think a conservative writer would care more about families and communities than market opportunities.) Worse yet, perhaps, by wrapping oneself in the discourse of national development and aggregate economic data, one forecloses on an opportunity for human sympathy. As Adam Smith knew, sympathy is crucial for the extension of the self beyond egotism, naturalized greed, and unwitting immorality. It is the stuff of human community.

And that is why we are fortunate to have this photograph from the cemetery in Najaf, Iraq.

Having finally located the grave site of her son who was abducted and murdered five years ago, Hassna Mirza grieves. What else can she do? She is plopped down on the ground like an old dog, disconsolate, body shrouded, legs and hands inert, mouth open in a long wail as if grief were running through her, as if grief and gravity were one. Other graves, some marked and some unmarked, extend in all directions to the horizon, as if she now resided in a perpetual city of mourning. The omnipresent sand has covered everything, ashes to ashes and dust to dust, as if blanketing identity and memory alike with the pale uniformity of inanimate oblivion. All that remains, for the moment, is her pain, weighing her down but also bonding her to her beloved.

And to us, if we are willing to admit to the deep, tragic, painful connections between her world and ours. The invasion of Iraq has caused untold suffering in both the US and Iraq, and no amount of economic development and nation building can undo that damage. Nor is this a matter of finally making right. It’s about accepting a common history of pain. Perhaps it’s also the case for why nation building has to start at home.

Reactions

Comments Powered by Disqus